News & Views

Print This Post Print This Post

May 17th, 2014

The Unique Style of

A Venetian Artist:

Carlo Crivelli &

His Golden Paintings

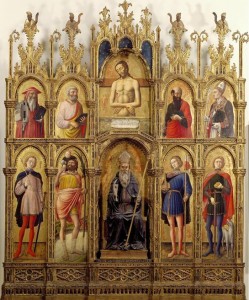

Andrea Mantegna, Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1450, tempera on canvas, transferred from wood, 15¾″ x 21⅞″ [40 x 55.6 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.  Bartolomeo Vivarini, The Death of the Virgin (1485, tempera on wood, 74¾″ x 59″ [189.9 x 149.9 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gallery 606 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art bears the title Venice and North Italy in the 15th Century. Included on its walls are paintings by Andrea Mantegna ( Adoration of the Shepherds) and Bartolomeo Vivarini ( The Death of the Virgin). Some distance from those works, in Gallery 627 under the heading North Italian Gothic Painting, The Met grouped Carlo Crivelli’s paintings, including his 1476 Pietá, with artists from “The centers of Northern Italian painting…,” deliberately excluding Venice. 1

Yet in almost all the work Crivelli signed, he made a point of reminding the world that he was “Veneto” (Venetian).2 Born in Venice in the early 1430s, he left little material evidence of his life there before 1457 court records note his status as an independent master. Sentenced at that time for his affair with a married woman, the young artist spent six months in prison and then, probably not long after his release, left the city. Over the course of his artistic career, Crivelli traveled among and worked within an assortment of cities in the north and Dalmatia, ultimately becoming closely associated with the Marches. He was never again documented in Venice.3

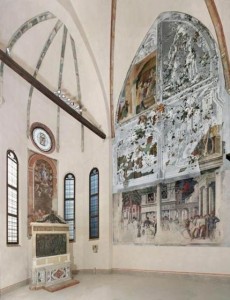

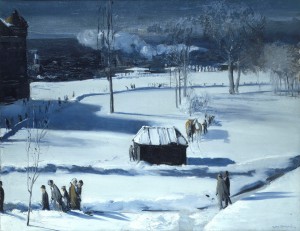

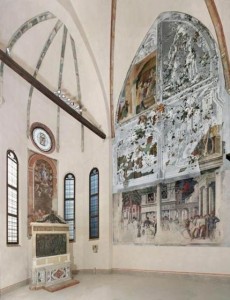

Andrea Mantegna, Ovetari Chapel, Padua (1447-1456, fresco). The Met has separated Crivelli from contemporaries linked to his development via Antonio Vivarini’s workshop on Venetian Murano, where he probably received his early training, and Francesco Squarcione’s studio school in Padua, where Mantegna was a rising star.4 As the university town of Venice, Padua was for a time during the mid-1400s “the most creative centre of Renaissance art in all of northern Italy.”5 It drew artists like Vivarini and Mantegna, who worked opposite each other on the Ovetari chapel between 1447 and 1450, and it might have been a stopover for Crivelli as well.6

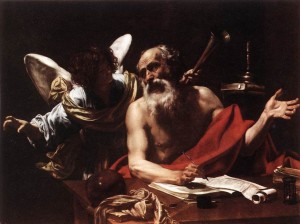

Antonio Vivarini, Saint Peter Martyr Healing the Leg of a Young Man (1450s, tempera and gold on wood, 20⅞″ x 13⅛″ [53 x 33.3 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. For his multi-panel altarpieces, Crivelli preferred ornate frames, relied heavily on gold over raised gesso as background for single-figure compositions of saints, and rendered naturalistically plants and other still-life objects. These elements echo the work of Antonio Vivarini, who (unlike his younger brother Bartolomeo) was never completely won over by the Renaissance practices taught in Squarcione’s school–techniques that soon caught on in Venice. This connection is acknowledged at The Met by the display in Crivelli’s gallery of Antonio’s 1450s tempera-and-gold Saint Peter Martyr Healing the Leg of a Young Man.

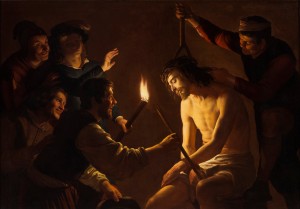

Antonello da Messina, Christ Crowned with Thorns (n.d., oil, perhaps over tempera, on wood, 16¾″ x 12″ [42.5 x 30.5 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.  Antonello da Messina, Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1470, oil on wood (10⅝″ x 8⅛″ [27 x 20.6 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The segregation of these four artists into two different galleries seems to reflect differences in their responses to the advent of a new kind of painting. In fact, in the same gallery as Bartolomeo and Mantegna are two panel paintings by Antonello da Messina ( Christ Crowned with Thorns and Portrait of a Young Man), both done in the oil medium he is credited with popularizing in Venice on his visit there in 1475-76. 7

Although Crivelli absorbed some of the lessons of the Renaissance, he remained steadfast in his commitment to tempera, a fast-drying medium that lends itself–even requires–a style reminiscent of pen-and-brush ink drawings. Finding in Mantegna’s work a powerful example of the expressive power of line only served to reinforce Crivelli’s personal preference for outlining forms and using hatch marks to create shadows.

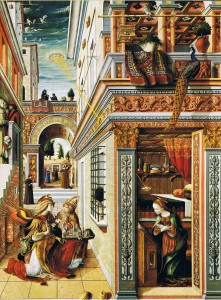

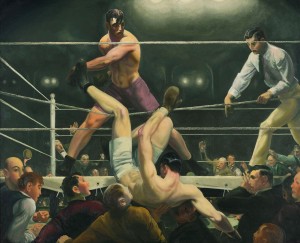

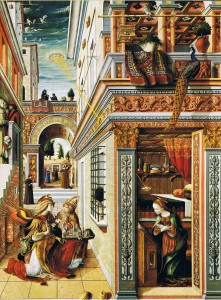

Carlo Crivelli, The Annunciation with Saint Emidius (1486, egg tempera and oil on canvas, 81½″ x 57¾″ [207 x 146.7 cm]). The National Gallery of Art, London. Contemporary in his use of perspective–most dramatically in the 1486 Annunciation with Saint Emidius–and in his illusionistic naturalism–noticeable in the profusion of still life objects in so many of his paintings (especially the enthroned Madonnas), Crivelli took what he liked and leaving the rest perfected an inimitable style that attracted few followers. 8 With a fastidiousness for decorative detail bordering on obsessive-compulsivity, he created visual feasts for the eye.

Carlo Crivelli, Saint George (1472, tempera on wood, gold ground (38″ x 13¼″ [96.5 x 33.7 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Just two paintings down the wall from the much quieter Pietá, Crivelli’s 1472 Saint George, aglow in his blue, white and gold armor accented with red straps, holds a candy-cane-striped lance. The artist designed a stunning cuirass that sports lion-headed shoulder protectors and includes a leonine face on the breastplate. Sharp blue rays emanate from the knee plates and lions’ mouths, finding resonance in the pointed incisors and long snout of the slain dragon who lies dying behind St. George, the broken-off tip of the saint’s lance lodged in its head. Crivelli’s relish for bright colors, gleaming gold and intricate design is obvious here, but so are the foreshortened feet, one of which protrudes over the marble ledge into the viewer’s space, reminding onlookers of the artist’s keen interest in three-dimensional space.

Carlo Crivelli, Madonna and Child Enthroned (1472, tempera on wood, gold ground, 38¾″ x 17¼″ [98.4 x 43.8 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.  Bartolomeo Vivarini, Madonna of Humility (c. 1465, tempera and gold on wood, 23″ x 18″ [58.4 x 45.7 cm]). Saint George’s graceful hand-on-hip contraposto pose reflects a closer affinity to the work of Bartolomeo Vivarini than that of his older brother Antonio, whose figures lack the animation with which Crivelli imbues his. Similarly, in the 1472 Madonna and Child Enthroned panel painting attached to the Saint George, the elaborately embroidered gold brocade with which Crivelli adorned his Madonna looks strikingly like the fabric with which Bartolomeo decorated his 1465 Madonna of Humility.

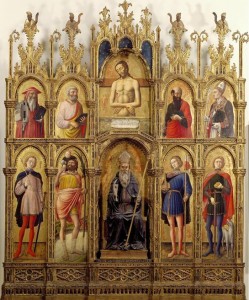

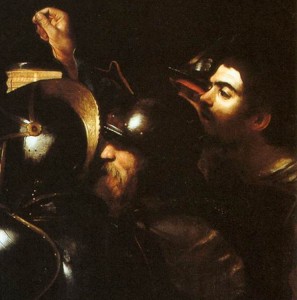

Antonio Vivarini, Pesaro Polyptych (1464). Pinacoteca Vaticana. For his 1476 Pietá, a scene of profound grief, Crivelli retained the gold-over-gesso background but toned down his colors in keeping with the somber subject matter. Originally part of a polyptych altarpiece in the church of San Domenico at Ascoli Piceno in the Marches,9 this lunette-shaped panel painting once occupied the position usually reserved for a Christ-Man of Sorrows, as in Antonio Vivarini’s 1464 Pesaro Altarpiece.

Carlo Crivelli, Pietà (1476, tempera on wood, gold ground, 28¼″ x 25⅜″ [71.8 x 64.5 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. In this representation of Christ after his crucifixion, Crivelli posed the dead body in a seated position in front of a ledge that makes more sense as a compositional device than as the sarcophagus assumed in The Met’s online catalog entry. 10 That the artist elected not to place the dead Christ’s body in its usual supine position on Mary’s lap suggests he might have purposely conflated the Pietá with a Christ-Man of Sorrows.

Here, the left arm of the dead Christ is draped over Mary’s left shoulder while she looks up into his lifeless face with its closed eyes and pallid skin. Her open mouth reveals upper teeth and tongue, as if caught in the middle of an agonized wail, and three large teardrops spring from her right eye. She wears a blue garment edged in reddish gold, damage to the paint surface of which reveals a higher-chroma-blue underpainting and Crivelli’s intentional muting of the overall color key of the painting.

Mary Magdalen appears at Christ’s right, the most colorfully attired of the four figures. Yet her green-lined red cloak, cool-blue dress with gold-embroidered edges, and gold-trimmed red bodice and sleeve were all rendered in a subdued manner appropriate to the narrative. Her golden-red hair cascades in rhythmic ripples from its central part. As she looks down at the wound in Christ’s left hand, three tears drop across her left check and one over her right. Creases form around the left corner of her mouth as she purses her lips, perhaps in the middle of a restrained sob.

In the background, a curly-haired male figure whose youth indicates he is John the Evangelist, opens his mouth and extends his tongue in an almost audible cry. With furrowed brow, lowered eyelids, and three tears coursing from his left eye and one from his right, he looks heavenward as if for an explanation of why this happened to his friend.

Crivelli bunched together his figures, confining them between the arch of the frame above and the horizontal line of the marble ledge below. Only the pierced hand of Christ escapes this claustrophobic space, drawing focus by breaking through the picture plane.

The four figures appear collaged onto the painting’s surface rather than situated in a three-dimensional space. With no indication of the structure on which it sits, the body of Christ mysteriously supports the weight of his mother Mary who throws herself at him in a desperate embrace as his lifeless head leans against hers. On the right, Mary Magdalene holds but does not quite lift Christ’s weightless left forearm. Behind the three-quarter-length figures, St. John the Baptist’s head floats free of a body barely hinted at by its neck and the white-trimmed collar of a brown garment. The flatness of the decorative gold backdrop–including the haloes–presses from behind, leaving little room for the unseen parts of the actors in this drama.

In keeping with his love of line, Crivelli created in this Pietá a symphony of visual rhythms, most obvious in the wavy hair of Christ and Mary Magdalene, the curly hair of John and the narrow bands of folds on Mary’s white head wrap. A spike on the far right of the crown of thorns perfectly overlaps one of the rays of Christ’s halo, and the pointy leaves of the golden background floral pattern further elaborate this theme. Lines pick out the form, with parallel hatching in areas of shadow but also in details like the random, curved lines of Christ’s pubic hair.

Despite Crivelli’s reliance on aspects of an increasingly out-of-fashion Gothic style, he showed interest in contemporary painting practices by using an external light source, which models form better, and dispensing with the use of a spiritual light emanating from one holy figure or another. With the hatch marks typical of tempera painting, he placed shadows strategically. Those below Mary’s right arm fall across Christ’s rib cage and bury in darkness the mildly bloody gash from the soldier’s spear. Those on Christ’s left arm provide a dark ground against which the left hand of Mary Magdalene stands out. Crivelli also used color to direct the eye, relating the green lining of the Magdalene’s cloak to the green of Christ’s crown of thorns, and the white of Mary’s head wrapping to that of the cloth across her son’s thighs.

While the grimacing, teary expressions depict emotional distress, Crivelli understated the traumatic nature of the event by cleaning up the blood from Christ’s forehead where the thorns penetrate below the skin on his forehead and leave evidence of their sharp presence by the mounds they raise. An area of redness is all that remains around the perfectly drawn spike hole on Christ’s left hand, hardly the evidence of torn flesh that would be expected under the circumstances. From Christ’s chest wound–painted to emulate the open mouths of Mary and John–seeps a narrow, transparent stream of blood that trickles down his torso, dividing into three lines that run down his abdomen.

Michele Giambono, Man of Sorrows (c. 1430, tempera and gold on wood, 21⅝″ x 15¼″ [54.9 x 38.7 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Crivelli’s Pietá tells a story about suffering. In contrast, Michele Giambono’s 1430 Man of Sorrows evokes in the viewer empathy for the afflicted. In this tempera-and-gold panel painting that sits in a vitrine just a few feet away from Crivelli’s work in the North Italian Gothic gallery, the older Venetian artist used gesso to model in relief the crown of thorns and the blood that flows copiously from the victim’s wounds. The faces of Christ and St. Francis are realistically rendered, further contributing to the image’s emotional pull. In comparison, Crivelli’s faces take on a highly stylized appearance that creates a comfortable distance between the painful subject matter and its audience.

Like Bartolomeo’s faces in The Death of the Virgin, those in Crivelli’s Pietá convey the idea of emotion rather than its actual appearance (note the calculated number of tear drops), perhaps in keeping with the humanistic trend of the time. More curious is the lack of believable space in a painting by an artist who established it in other works. Perhaps Crivelli’s goal here was to bring the narrative action as close as possible to the worshiping public by pressing the figures up against the picture plane.

Whatever Crivelli had in mind, in this Pietá he combined the best of his earlier influences with his own unique vision. In this, one of his sparer compositions, he arranged three mourners around the body of a recently tortured and murdered loved one. Their grief-stricken expressions reveal the pain that wracks their bodies while the oddly serene look on the victim’s face shows that unlike them, he is now free of human suffering. It is a picture that could only have been painted by Carlo Crivelli, Veneto.

____________________________

1 Gallery 627 description, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

2 Zampetti, Pietro, Carlo Crivelli (Florence: Nardini Editore, 1986), 12.

3 Lightbown, Ronald, Carlo Crivelli (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 3.

4 Ibid, 4.

5 Humfrey, Peter, Painting in Renaissance Venice (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 53.

6 Lightbown, 3.

7 Hills, Paul, Venetian Colour (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 162.

8 Rushforth, G. McNeil, Carlo Crivelli (London: George Bell and Sons, 1908), 78.

9 Zampetti, 140.

10 The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Catalog entry for “Pietà, Carlo Crivelli (Italian, Venice [?], active by 1457-died 1495 Ascoli Piceno),” 2011. Accessed February 16, 2014. http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/436053.

Posted in Art Historical Musings |

Print This Post Print This Post

December 1st, 2013

Through Spanish Eyes

Ribera

by Javier Portús

[To view the slide show in a separate tab while reading the text, place the mouse pointer over the first slide, right click, select <This Frame>, then <Open Frame in New Tab>.]

http://www.slideshare.net/DFeller2/ribera-28721572?from_search=5

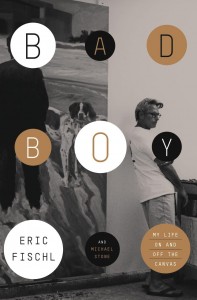

[Image 1: Book cover.]

When the Chief Curator of Spanish Painting (up until 1700) at the Prado Museum in Spain decides to write a monograph on Jusepe de Ribera as part of that institution’s series spotlighting several of its art stars, it’s a given that he assumes the artist belongs in his country’s pantheon. Lest there be any doubt, the note on the inside front dust jacket of Javier Portús’s Ribera claims the painter and printmaker as a “leading figure in the baroque Spanish tradition–alongside El Greco, Velázquez and Zurbarán,” and names him José rather than the more Italian, Jusepe.

In the very first paragraph, under the chapter heading “In Search of an Identity,” Portús acknowledges this inherent bias and addresses the tradition of categorizing Ribera as a Spanish painter even though the artist left Spain when he was barely twenty and never returned to the land of his birth. Aware of the exalted status of artists in Italy, Ribera chose it over a Spain that was “‘a pious mother to foreigners but a very cruel stepmother to her own native sons.’”

[Image 2: Map of Iberian Peninsula, 1270-1492.]

Born in Xátiva, Valencia, in 1591, Ribera vanishes in the record for the next twenty years. No documentation has so far been uncovered beyond his baptismal certificate, dated February 17, 1591, that indicates his whereabouts prior to June 11, 1611, when a record of payment for a painting places him in Parma, Italy.

There are, however, documents indicating that when Ribera was six years old, his father remarried and did so again ten years later. It’s likely that the reasons for the remarriages were the deaths in childbirth, or from illness, of the boy’s first two mothers. Perhaps the second loss, before the boy was sixteen, prompted the fledgling artist to leave home and seek his fortune where his work would be more highly regarded, a possibility that squares with recent scholarship that pushes back the date of his arrival in Italy–specifically Rome–by several years.

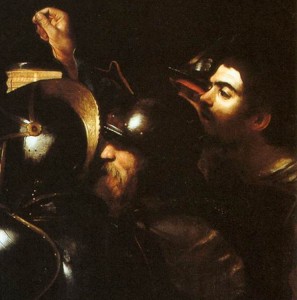

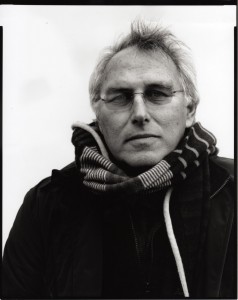

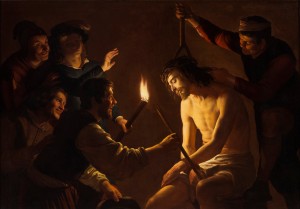

By 1613, Ribera was well enough established to receive an invitation to a meeting at the Accademia di San Luca in Rome. During his subsequent three years in that city, he came in contact with the legacy of Caravaggio, an artist who had fled the city by 1606, leaving behind many followers and plenty of artwork to impress and influence the young Spanish immigrant. That Ribera led “a disordered life” there suggests that he fell in with the artists who once accompanied Caravaggio on his nightly rounds and got into street brawls and entanglements with the law.

Portús picks up his narrative in Rome, laying out his position regarding Ribera’s national affiliation, first by noting how the painter’s style evolved from Caravaggesque tenebrism and undefined space to lighter-colored, multi-figured compositions in architectural settings, and then by drawing attention to the manner in which the artist signed his name.

[Image 3:

–Denial of St. Peter (c. 1614, oil on canvas, 64.2″ x 91.75″ [163 x 233 cm]). Galleria Corsini, Rome.

-Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Denial of St. Peter (c. 1610, oil on canvas, 37″ x 49.4″ [94 x 125.4 cm]). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Calling of St. Matthew (1599-1600, oil on canvas, 127″ x 130″ [322 x 340 cm]). San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome.]

That Caravaggio’s tenebrism had a strong impact on Ribera’s early works is readily accepted by Portús, who finds in the younger artist’s “painterly technique and…enthusiasm for chiaroscuro effect” a direct link. He seems to miss the other commonalities between the master and the newly minted artist that continued well into Ribera’s later years, similarities that include more than just the raking light that originates on the left. Caravaggio’s theatrical compositions placed gesturing, three-quarter-length figures, wearing dramatic facial expressions, in an undefined space, characteristics evident in the paintings Portús selects to connect the two painters.

In his Denial of St. Peter (c. 1614), Ribera borrows the denying saint’s pose directly from Caravaggio’s painting of the same name (about 1610) and includes figures around a table, a common theme among the Caravaggisti and traceable to Caravaggio’s The Calling of St. Matthew (1599-1600), which is also the source of Christ’s pointing finger in the younger painter’s Resurrection of Lazarus (c.1616), which Portús mentions in his comparison of the two artists’ work.

[Image 4:

–The Resurrection of Lazarus (c.1616, oil on canvas, 55″ x 90½” [171 x 289 cm]). Museo del Prado, Madrid.

-Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Calling of St. Matthew (1599-1600, oil on canvas, 127″ x 130″ [322 x 340 cm]). San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome.

-Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Raising of Lazarus (1608-9, oil on canvas, 149.6″ x 108.3″ [380 x 275 cm]). Museo Nazionale, Messina.]

The curator, in noting the power of tenebrism to heighten emotions, sees a qualitative difference between the “tumult and anxiety” in Caravaggio’s Raising of Lazarus (1608-9) compared with the toned down emotional content of Ribera’s version, observing too the contrast between the “deliberate crowding” in the former and a “clear distinct space” for each figure in the latter. It seems strange, though, that the writer would choose a painting with a compositional format so removed from Ribera’s and from the more relevant Caravaggios with their three-quarter-length figures in shallow space.

[Image 5: The Communion of the Apostles (1651, oil on canvas, 157.5″ x 157.5″ [400 x 400 cm]). Certosa di San Martino, Naples.]

Having compared and contrasted Ribera’s early Caravaggesque style with that of its originator, Portús goes on to illustrate how that style gradually evolved over time, retaining its naturalism. He uses the large-scale Communion of the Apostles (1651) done the year before Ribera’s death to chart those changes, particularly in the way the painter has brightened his palette and opened up space with a blue sky populated by flying angels and an arcade receding to some unspecified place. Portús sees the drapery across the top as the artist’s allusion to the painting’s artificial nature, though it could just as easily be read as a stage curtain pulled back to reveal the dramatic event. Marveling at Ribera’s skill, the writer points out the interplay of the five hands’ participating in this first offering of holy communion, as well as the parallel action of the kneeling St. Peter’s left hand with the right foot of the standing Christ.

[Image 6: The Immaculate Conception (1635, oil on canvas, 67.7″ x 112.2″ [502 x 329 cm]). Church of the Convento de las Agustinas Recoletas de Monterrey, Salamanca.]

To further note Ribera’s gradual move away from a Caravaggesque style, Portús cites two other paintings–The Immaculate Conception (1635) and St. Januarius Emerges Unscathed from the Oven (1646), both undeniably different in appearance from early works. The reader will discover in a matter of pages, however, that these paintings were contemporaneous with others that continued to include many elements from Ribera’s Rome years.

[Image 7:

–St. Januarius Emerges Unscathed from the Oven (1646, oil on copper, 126″ x 78.75″ [320 x 200 cm]). Real Cappella del Tesoro di San Gennaro, Naples.

-Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Martyrdom of St. Matthew (1599-1600, oil on canvas, 127.2″ x 135″ [323 x 343 cm]). San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome.]

In fact, a closer look at the composition and figures in the St. Januarius demonstrates Ribera’s memory of Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of St. Matthew (1599-1600), which he would have seen in the chapel where it did (and still does) reside in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome. First and most obvious is the quote of Caravaggio’s open-mouthed boy, wearing white and looking back over his shoulder at the impending execution. Ribera mirrors that expression and pose in his young man in red on the left, who looks out at the viewer. Less direct but clearly related is the placement of a foreground figure in each lower corner to frame the action. Like Caravaggio, Ribera positions one with his back to the audience and the other stretched out on the ground, body facing forward and head turning back toward the unmarred saint. Tumult abounds in both pictures.

The debate about Ribera’s nationality takes on new complexities once he relocates to Naples, where he is documented by 1616. The bustling city, capital of a Spanish viceroyalty, offered the artist opportunities to market himself to his compatriots, particularly the procession of viceroys who came and went during the 36 years Ribera lived there. Through commissions and sales to patrons who moved between Naples and Spain, the painter spread his influence to at-home Spanish artists, the names of which Portús lists as he picks up the thread about nationality with a focus on Ribera’s signature.

[Image 8: Balthasar’s Vision (1635, oil on canvas, 20.5″ x 25.2″ [52 x 64 cm]). Palazzo Arcivescovile, Milan.]

In Spain, writers like Francisco Pacheco claimed the artist as their own; in Italy, he was known as lo Spagnoletto, a nod to his place of origin. A diminutive with negative connotations, the nickname translated to the Spanish el españoleto but was bypassed by Ribera when he settled on signature styles. Portús points out how the painter signed an unusually large number of works compared to other artists of that time and chose the more dignified español over the well-known españoleto to emphasize his association with Spain.

The curator delves into a variety of signature issues in trying to discern whether Ribera identified himself as first and foremost Spanish. Whatever else the proliferation of signed works might indicate, they show that Ribera was “greatly concerned with leaving written evidence of the authorship of his work,” and Portús finds plenty of examples to prove that point.

Often the signatures call attention to themselves as integral parts of the composition. In the small canvas, Balthasar’s Vision (1635), Ribera painted “Jusepe de Ribera español F. 1635″ in the same script used by the hand that writes on the wall.

[Image 9:

–Drunken Silenus (1626, oil on canvas, 72.8″ x 90.2″ [185 x 229 cm]). Museo di Capodimonte, Naples.

-Detail of signature. Drunken Silenus (1626, oil on canvas, 72.8″ x 90.2″ [185 x 229 cm]). Museo di Capodimonte, Naples.]

In the Drunken Silenus (1626), in the lower left corner, a snake–that symbol of envy–tears apart a scrap of paper on which is written the artist’s name.

[Image 10: The Communion of the Apostles (1651, oil on canvas, 157.5″ x 157.5″ [400 x 400 cm]). Certosa di San Martino, Naples.]

In The Communion of the Apostles, in the lower left, the piece of paper is so large as not to be missed.

[Image 11:

–Large Grotesque Head (1622, etching, 8.5″ x 5.7″ [21.7 x 14.5 cm]). Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna.

–Head of a Man with Little Figures on His Head (c. 1630, pen and brown ink with brown wash over some black chalk on paper, 611/16″ x 41/16″ [17 x 10.4cm]). Philadelphia Museum of Art.]

Signed works like these are more abundant after 1625, but the desire to publicize his prowess as an artist is already evident several years earlier in etchings Ribera created and circulated to advertise his wares and generate income. Unlike paintings, prints lend themselves to mass production and widespread distribution, and Ribera exploited both attributes to reach potential customers throughout Europe.

These mostly signed works also constituted a showcase for the artist’s drawing skills and his command of the printmaking process. Portús sees the etchings, seventeen in number and created prior to 1630, as vehicles for Ribera’s “highly questing creative spirit,” observing in them “an unequivocally Riberesque world…of narrative resources, human types, varied subject matter and different emotional climates.” In the Large Grotesque Head (1622), the artist explores a particular type and in the drawing of a Head of a Man with Little Figures on His Head (c. 1630) he displays a touch of whimsy and playfulness, though a darker meaning might lurk nearby. Might those little men represent obsessional thinking and/or auditory hallucinations?

[Image 12:

–Calvary (c. 1618, oil on canvas, 132.25″ x 90.5″ [336 x 230 cm]). Collegiate Church, Osuna.

-Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Martha and Mary Magdalen (1595–96, oil and tempera on canvas, 39⅜” x 53″ [100 x 134.5 cm]). Detroit Institute of Arts.]

If Ribera identified himself as Spanish, his paintings anchor him firmly in the Italian Baroque and were seen as such by two practiced connoisseurs, Philip IV and Diego Velázquez, when they selected his artwork while redecorating El Escorial in the late 1650s. His “thoroughly Italianate” style qualified him as the only Spanish painter to be displayed in the company of such Italian masters as Titian and Veronese.

Straddling both worlds began to pay off for Ribera soon after he landed in Naples, with commissions for paintings that arrived at their destination–the Collegiate Church in Osuna, Spain–by 1627. Among these was a crucifixion, Calvary (c. 1618), a tour de force in tenebrism and emotion, whose colorful fabrics bring to mind those in Caravaggio’s Martha and Mary Magdalen (1595-96).

[Image 13:

-View of the nave of the Certosa di San Martino, Naples.

-Paintings of the prophets Joel and Amos above the church arches in the Certosa di San Martino, Naples.]

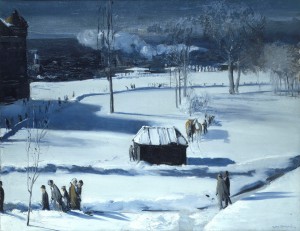

A decade later, Ribera would execute in Naples a series of prophets for the Certosa di San Martino, a monastery on a hill overlooking the city. The painter met the challenge of devising compositions that conformed to the irregular spaces into which they were to be placed by relating each figure to its surrounding architecture. Portús mentions that although a number of Ribera’s paintings did find their way to religious institutions like the Osuna church and Carthusian Monastery, commissions like these were rare. Instead, the artist specialized “in medium-size and small paintings, conceived for private collections and chapels and easily transportable,” mostly of a sacred nature.

[Image 14: St. Bartholomew (c. 1613, oil on canvas, 49.6″ x 38.2″ [126 x 97 cm]). Fondazione Roberto Longhi, Florence.]

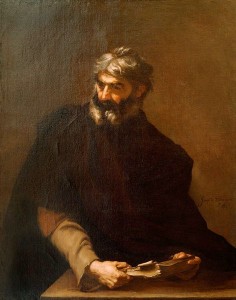

Portús soon delves into the “Riberesque” world depicted in those compositions, one “in which joy or happiness is hard to find, in which laughter creates a sinister effect and tenderness is rare.” At the same time, themes of “piety, stoicism, devotion, austerity, meditation and drama abound,” with “cruelty and the grotesque” an integral part of much of his work. Most of those qualities, particularly the last two, are quite evident in the bloodless but flayed St. Bartholomew (c. 1613) who holds in his right hand the instrument of his torture and drapes over his left arm his recently removed skin, replete with facial features and hair. The theme of flaying remains of interest to Ribera, who comes back to this saint in future paintings and also explores the myth of Marsyas and Apollo.

Of Ribera’s style, Portús notes its naturalism, as seen in the specific human types that populate the artist’s compositions, and its “precise and descriptive pictorial idiom.” He describes how the painter clothes his humble characters in earthy-colored, outdated garments that emphasize their poverty, and gives them bearded–they are mostly male–expressive faces with wrinkled, weatherbeaten skin. Portús traces this rejection of the prevailing Renaissance preference for idealization to certain antique Roman sculpture, while missing the possible influence of Caravaggio’s depiction of religious figures as ordinary people who sometimes reveal their dirty feet.

[Image 15:

–Smell (c. 1615, oil on canvas, 45.25″ x 34.65″ [115 x 88 cm]). Private collection, Madrid.

–Sight (c. 1615, oil on canvas, 44.9″ x 35″ [114 x 89 cm]). Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico, DF.]

Among Ribera’s secular subjects, a series of the five senses dates to his early years in Rome and reappears in later paintings that dramatically demonstrate the evolution of his style. A long-standing traditional theme in Western art, the senses presented opportunities for innovation that, according to Portús, Ribera exploited by situating all the figures behind a table, directing their gaze toward the viewer (except for the blind man in Touch [1615]), and giving them objects and behavior that illustrate the pictured sense. Light streams in from the upper left, illuminating the detailed depiction of still-life objects, facial features and cloth. Portús notes that in Sight, Ribera equipped the character with a telescope, a device only recently invented by Galileo.

[Image 16:

–Touch (1615, oil on canvas, 44.85″ x 35″ [114 x 89 cm]). Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California.

–Touch (1632, oil on canvas, 49.2″ x 38.5″ [125 x 98 cm]). Museo del Prado, Madrid.]

When the painter returned to the theme of the senses some fifteen years later with his 1632 Touch, he retained the trope of using a blind man perceiving a sculpted head to emphasize the absence of sight. What Portús calls the “unnecessary” portrait painting on the table in the 1615 version, echoed by a similar object in the later one, is ascribed to Ribera’s need to keep the composition of this sense parallel with that of the others in the series. It might also refer to the paragone, that age-old competition between sculpture and painting for highest artistic honors.

The most immediate differences between the two paintings occur in the lighting, range of color, pose, attire and detail with which Ribera renders it all. The raking light from the left that divides the background diagonally in the first work is replaced by a mostly dark backdrop that lacks any direct relationship to the light that picks out the details in the face, hands and sculpture. Where the blind man, wearing what might be a sculptor’s smock, turns from the viewer in the earlier version, he now wears tattered clothing and faces front, handling a less classical head. Finally, Ribera has aged him by greying his beard and wrinkling his skin.

[Image 17: Protagoras (1637, oil on canvas, 48.88″ x 38.75″ [124 x 98 cm]). Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut.]

The general layout the painter devised for picturing the senses became a handy template to be used freely in subsequent single-figure paintings. Using a limited palette, Ribera represented three-quarter-length philosophers and saints against a dark background, sitting or standing behind or near a table adorned with still-life objects symbolic of the subject–all depicted with remarkable detail.

Counting over thirty paintings of philosophers done by the artist, Portús writes about them at length, concluding that anyone standing before them “might believe they are in the presence of a collection of ragged ‘secular saints.’” In comparing a couple of Ribera’s philosophers to similarly presented saints, he observes that the clothing of the saints is considerably neater.

[Image 18:

–Democritus (1614, oil on canvas, 40.15″ x 29.9″ [102 x 76 cm]). Private collection, London.

–Democritus (1630, oil on canvas, 49.2″ x 31.9″ [125 x 81 cm]). Museo del Prado, Madrid.]

In revisiting one philosopher in particular, Ribera again provided an opportunity to compare the changes over time in his thinking about his subject and his art. The Democritus (1614) from his Rome years has a similar palette and lighting scheme as the contemporaneous Touch, while the Democritus executed in 1630 displays changes comparable to those associated with the 1632 Touch. In both renditions of Democritus, Ribera has associated philosophy with poverty by emphasizing the torn clothing.

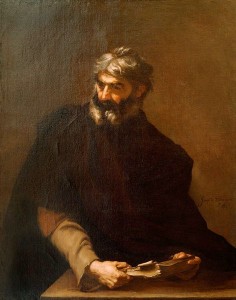

[Image 19: St. Jerome and the Angel of Judgment (1626, oil on canvas, 142.5″ x 64.5″ [362 x 164]). Museo di Capodimonte, Naples.]

Having focused mostly on paintings from Ribera’s years in Rome, Portús now moves with him to Naples, where the painter relocated around 1616, married and added to his repertoire large-format canvases of saints, many of which are shown at the moment of their martyrdom in various stages of exposure. As the writer puts it, Ribera “discovered one of the methods he would apply with great frequency and success [to transmit] feelings of religious devotion: description of flesh…[that endows] the human body with special significance as the scenario of saintliness.” Portús attributes this change of focus to Ribera’s encounter with a different client base, by implication less sophisticated.

An early example of Ribera’s exploitation of flesh’s potential for expressiveness is his St. Jerome and the Angel of Judgment (1626). In this vertical composition, the artist has raised the saint’s arms to expose his brightly illuminated bare torso, making it the center of interest and a testament to the vulnerability of the body, appropriate for a scene where St. Jerome is being called to his maker. The lighting, gestures and threatening dark clouds heighten the drama and make practically audible the trumpet’s ominous blare.

[Image 20:

–Magdalena Penitent (1637, oil on canvas, 38.2″ x 26″ [97 x 66 cm]). Museo del Prado, Madrid.

–St. Mary the Egyptian (1641, oil on canvas, 52.4″ x 41.75″ [133 x 106 cm]). Musée Fabre, Montpellier.]

Two paintings of penitent women–their creation separated by just a few years–demonstrate the impact bare skin can have on the expressive tone of a composition. In Magdalena Penitent (1637), a fully clothed Mary is shown with the furrowed brow and lowered upper eyelids of sorrow as she leans her head on her prayerfully clasped hands, which in turn are supported by a skull they partially embrace. Her remorse is as evident as her beauty.

In the starkly different St. Mary the Egyptian (1641), who is often confused with Mary Magdalene, Ribera places this patron saint of penitents in a barren environment near a skull and crust of bread. Hands joined in prayer, Mary of Egypt gazes upward, her ascetic penance underscored by the heavy brown cloth that doesn’t quite cover her weathered skin. By exposing her flesh, Ribera infused the scene with the same sense of vulnerable mortality that he did in his St. Jerome and the Angel of Judgment, a feeling absent from his lovely Magdalena Penitent.

[Image 21: The Martyrdom of St. Philip (1639, oil on canvas, 92.1″ x 92.1″ [234 x 234]). Museo del Prado, Madrid.]

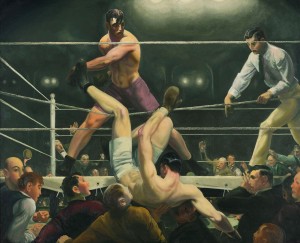

Further exploiting the expressive potential of nakedness, as Portús observes, Ribera arrived at a formula for his martyrdom narratives, key elements of which are nude or partially draped male saints whose nakedness and expressions of meditative acceptance stand in sharp contrast to those of their clothed torturers, intent on their murderous tasks with sadistic glee. In some of these paintings, figures populate the background, variously watching or not.

In one example, The Martyrdom of St. Philip (1639), two diagonals bisect the picture and meet at the saint’s spotlighted rib cage, which comes into view as his body is slowly hoisted up–his wrists tied to the crosspiece of his crucifixion. Among the spectators, expressions range from the amused interest of the man on the right who supports his head on his hand to the knowing look on the woman in the lower left who holds a baby and stares out at the viewer, implicating all in this act of torture.

[Image 22:

–Scene of Torture (1637-1640, pen and brown ink, brown wash, 5⅜” x 10⅝” [13.6 x 27.2 cm]). Teylers Museum, Haarlem.

–Torture Scene (N.d., drawing, no dimensions). Museo Civico, Bassano del Grappa.]

Ribera’s personal interest in such scenes of torture shows up in drawings he executed “for which no sources have been found in the Scriptures.” An undated one, apparently in pen and brown ink with brown wash, shows a tree festooned with miniature figures–easily mistaken for acrobats–involved in a hanging. A man in a small audience, with a child hanging onto him, indicates the performance to a newcomer who tips his hat in friendly greeting. No one seems troubled by the unfolding events. In another ink drawing, the executioner is about to hack into his defenseless victim who is stretched out between, and tied to, two sets of posts.

[Image 23: The Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew (1617, oil on canvas, 70.5″ x 52.75″ [179 x 139 cm]). Collegiate Church, Osuna, Spain.]

As mentioned earlier, flaying held a particular fascination for Ribera who explored that form of torture in at least five versions of The Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew. The Rome 1613 portrait of the saint holding his skin was followed in 1617 by perhaps the artist’s first Naples edition, which has an almost clinical quality to it.

[Image 24: The Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew (1628, oil on canvas, 57″ x 85″ [145 x 216 cm]). Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina, Florence.]

Over the years, Ribera would create additional compositions portraying St. Bartholomew, each exemplifying his stylistic preferences at the time.

[Image 25: The Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew (1630, oil on canvas, 79.5″ x 60.2″ [202 x 153 cm]). Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona.]

[Image 26: The Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew (1634, oil on canvas, 40.9″ x 44.5″ 104 x 113 cm]). National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.]

In the 1634 version, he simplified the composition by eliminating figures and zooming in on the face of the emotionally detached executioner who regards his victim with curiosity as he sharpens his knife. St. Bartholomew looks heavenward as if seeking out some source of comfort in this moment where his faith is being tested.

[Image 27:

–Apollo and Marsyas (1637, oil on canvas, 71.6″ x 91.3″ [182 x 232 cm]). Museo di Capodimonte, Naples.

-Detail of Marsyas’s face, flipped.

-Detail of Study of Noses and Mouths (c. 1622, etching). Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna.]

In discussing Ribera’s treatment of emotions, Portús isolates his special interest in those “related to devotion, piety, cruelty and pain,” recalling drawings and prints like the Study of Noses and Mouths (c. 1622) to illustrate the artist’s “penchant for these themes and for the grotesque.” The curator connects the wide-open mouth of that etching to the victim’s scream in Apollo and Marsyas (1637), a distinctly different response to the slicing knife from that of St. Bartholomew in the 1630 version of his ordeal.

[Image 28:

-Detail of Marsyas’s face, flipped, Apollo and Marsyas (1637, oil on canvas, 71.6″ x 91.3″ [182 x 232 cm]). Museo di Capodimonte, Naples.

-Detail of face, flipped, The Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew (1630, oil on canvas, 79.5″ x 60.2″ [202 x 153 cm]). Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona.]

Portús observes that in Ribera’s depiction of mythological subjects, “their facial expressions…invariably reveal all the horror…[while] the attitude of the saints is always one of piety and acceptance of torture,…a highly effective means…to convey religious feeling.” This difference is apparent in the faces of Marsyas and St. Bartholomew; the former screams in agony and looks directly at the viewer, while the latter contains his anguish and rolls his eyes upward in an attempt to mentally escape his pain.

[Image 29: The Trinity (1635, oil on canvas, 89″ x 46.5″ [226 x 118 cm]). Museo del Prado, Madrid.]

Using the emotionally expressive figures in the colorful St. Januarius Emerges Unscathed from the Oven as a bridge back to his opening thesis about Ribera’s later change in direction toward a less tenebristic style, Portús attributes the appearance in the 1630s of an “extension of the artist’s palette toward warm, sumptuous tones…[and] an engaging, relaxed, expansive piety…expressed through marked chromatic sensuality” to the Neo-Venetianism that was sweeping across Italy, and with the arrival in Naples during that decade of a number of classicizing artists. He cites The Trinity (1635) as one of several works that exemplify this shift.

A close look at that painting reveals more about the fluidity with which Ribera moved among his stylistic options than about any fundamental transformation in his artistic practices. Warm, high-value colors distinguish the heavenly sphere from the lower-register darkness out of which angels emerge and carry the body of Christ, whose pale skin and white shroud contrasts dramatically with the shadowy background.

[Image 30:

–St. Jerome in His Study (1613, oil on canvas, 48.4″ x 39.4″ [123 x 100]). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

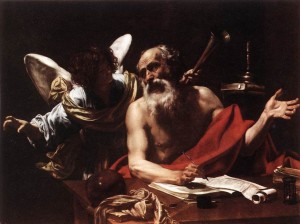

–St. Jerome Penitent (1652, oil on canvas, 30.4″ x 28.3″ [77.2 x 71.8]). Museo del Prado, Madrid.]

Ribera’s style continued to mature with time and practice and while there are noticeable differences between St. Jerome in His Study (1613)–his first signed painting–and St. Jerome Penitent (1652)–the last signed one completed before his death in 1652 (a comparison with which Portús ends his discourse), he never abandoned the tenebrism of his youth.

In St. Jerome Penitent, the saint bares a softly-modeled, anatomically descriptive right shoulder and boasts a head of shaggy grey hair with matching beard. Even at this late date, Ribera found uses for his earliest technique of zooming in close on brightly lit, half-to-three-quarter-length figures accompanied by identifying still-life objects. In this St. Jerome, he applied paint with short, confident brushstrokes that follow the contours of forms and animate the hair, hallmarks of the adept and brilliant painter he had become.

The mature Ribera sharply contrasts with the younger one, however, in the degree to which his subject now engages with the viewer, as Portús astutely points out. In the 1613 St. Jerome in His Study, the saint is occupied with his writing, unaware of the observer. In the later St. Jerome Penitent, the figure is positioned closer to the picture plane and looks through it–if not directly at the audience at least in its direction. The 61-year-old Ribera seems to have evolved not just as an artist but also as a man far more conscious of the power of relationship.

[Image 31: Magdalena Ventura (The Bearded Lady) (1631, oil on canvas, 77.2″ x 50″ [196 x 127 cm]). Exhibited at the Museo del Prado, Madrid.]

The life of Jusepe de Ribera came to an end on September 3, 1652. No contemporary writer chose to immortalize this Spanish-Italian artist with a biography that would have preserved vital facts about his life. In the absence of such a record, posterity has been left with no information about his psychologically formative childhood years nor about his early training as an artist–where or with whom that might have been. Perhaps a new generation of art historians will be inspired to rummage around the archives of Xátiva and Valencia in search of the missing pieces that will finally fill in the blanks of this great artist’s life. Meanwhile, art lovers can continue to marvel at the enigma who painted with such veracity the stunning portrait of Magdalena Ventura (The Bearded Lady) (1631).

References

Brown, Jonathan. Paintings in Spain: 1500-1700. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

_____________. Velázquez: Painter and Courtier. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

Marandel, J. Patrice, ed. Caravaggio and His Legacy. New York: Prestel Verlag, 2012.

Peréz, Alfonso E., and Nicola Spinosa. Jusepe de Ribera 1591-1652. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992.

Portús, Javier. Ribera. Barcelona, Spain: Ediciones Poligrafa, 2011.

[A version of this review with footnotes is available. If interested, contact deborahfeller@verizon.net.]

Posted in Art Book Reviews |

Print This Post Print This Post

November 24th, 2013

Doing Together

What Can’t Be Done Alone:

An Integrative Approach to

Raped by Käthe Kollwitz

***********************************************

The Blind Men and the Elephant

by John Godfrey Saxe (1816-1887)

It was six men of Indostan,

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind.

The First approach’d the Elephant,

And happening to fall

Against his broad and sturdy side,

At once began to bawl:

“God bless me! but the Elephant

Is very like a wall!”

The Second, feeling of the tusk,

Cried, -“Ho! what have we here

So very round and smooth and sharp?

To me ’tis mighty clear,

This wonder of an Elephant

Is very like a spear!”

The Third approach’d the animal,

And happening to take

The squirming trunk within his hands,

Thus boldly up and spake:

“I see,” -quoth he- “the Elephant

Is very like a snake!

“The Fourth reached out an eager hand,

And felt about the knee:

“What most this wondrous beast is like

Is mighty plain,” -quoth he,-

“‘Tis clear enough the Elephant

Is very like a tree!”

The Fifth, who chanced to touch the ear,

Said- “E’en the blindest man

Can tell what this resembles most;

Deny the fact who can,

This marvel of an Elephant

Is very like a fan!”

The Sixth no sooner had begun

About the beast to grope,

Then, seizing on the swinging tail

That fell within his scope,

“I see,” -quoth he,- “the Elephant

Is very like a rope!”

And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong!

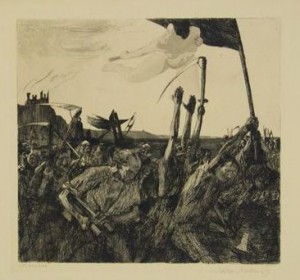

Raped (Vergewaltigt) (1907/08, etching on heavy cream wove paper, 11¾″ x 20⅝″ [29.9 x 52.4 cm)]. Plate 2 from the cycle Peasant War. Proof before the edition of about 300 impressions of 1908. Knesebeck 101/Va. Photo © Kollwitz Estate. The way to the blockbuster show led through a long corridor that at its beginning widened into an area whose walls the museum exploited for temporary exhibitions of works on paper too light-sensitive for permanent display. Attracted by the drawings and prints in this accidental gallery, some visitors slow for a more sustained look.

One image, which looked like an ill-kept garden, revealed itself via the wall text to be a 1907/8 etching called Raped by a German artist named Käthe Kollwitz,1 who lived between 1867 and 1945. Viewers who took the time to look more closely would detect amid the foliage a woman with legs splayed and head thrown back, the subject of the picture’s title. At that point most would move on to look at other works. Some few would linger, wanting to learn more about this depiction of sexual assault.

The only other information available at that moment–the description nearby on the wall–identified the brown-ink print as a plate from the Peasant War series executed on heavy cream wove paper. Although unschooled in art historical methods, an intrigued viewer might intuitively know that much could be gained by exploring every aspect of this simply-framed etching.

Drawing the viewer’s immediate attention and bisecting the bottom of the almost-double-square (approximately 12-by-21-inch) composition, the woman’s foot–set off from lighter surroundings by its dark sole–meets the picture plane and beckons the onlooker to follow its arch to the foreshortened, thick-set leg that disappears under a skirt. The eye continues along an arc, through the torso and extended neck, stopping at the chin beyond which lies the shadowed face with its features distorted by the angle of view.

Searching for the rest of her, the observer discovers behind a bent-over, wilted sunflower the right leg, forming a horizontal line with the top edge of the skirt and ending in a foot that points toward the upper left corner. Assisted by a nearby still-upright flower slanted at an angle running parallel to it, the foot directs the gaze to a blossoming sunflower in the background’s deep shadow, the form of which echoes the head of a barely discernible child with a pony tail (or braid) who drapes her right arm over a fence and looks down at the body before her. Faintly silhouetted against a patch of open space, the young girl can easily be missed by all but the most attentive viewers as she blends in with the leafy plants around her.

Once noticed, the child leads the eye to a structure suggested by two sets of vertical lines hiding in the dark recesses of the upper register–perhaps a house. Across the rest of this small patch of verdant landscape, damaged plants and flowers tell a story of struggle and recent destruction in what might have been a well-tended, backyard vegetable garden.

A shadow originating from outside the picture plane on the left ends in a point that meets the prone woman’s right foot and relates to her dark skirt. Cast by a structure with straight edges and therefore of human origin, its top boundary becomes one side of a flattened diamond, the other three edges of which are the overgrown part of the fence that supports the girl, its dark extension to the right, and the left side of the woman on the ground. Ominous in nature, the sharply angled shadow seems a stand-in for the recently-fled rapist.

Following the perimeter of that diamond shape brings the inquisitive observer to the figure’s left hand, the fingers of which curl around the edge of her torn garment near some trickles of blood on her torso and provide the final clue to the story. A peasant woman working in her garden has been raped and stabbed, then left for dead. Hearing the commotion and perhaps some screams, her daughter has come to see what happened and now stares sadly at the sight of her mother, wondering what to do.

Having followed the trail of clues and figured out the narrative, the formerly-naive tourist, seduced by a compelling work of art, has unwittingly entered the empirical world of the connoisseur. Questions tumble forth about the decisions that went into creating the etching. Who was Käthe Kollwitz? What was the Peasant War and why did the artist choose it as a subject? Why did she make a print instead of a painting? If this is a series, what does the rest of it look like? Most curious, why didn’t Kollwitz just tell her story directly and not force her audience to work so hard?

As often happens in exhibits, another visitor approaches and, noticing the engrossed tourist with nose scant inches from the print’s protective glass, engages in conversation about the piece. An art historian by trade, the newcomer eagerly offers information about a favorite artist, her work and her art. An exchange ensues.

First they talk about the etching itself. When the tourist points out the little girl in the background and the trickles of blood near the victim’s left hand, the art historian is surprised, having never before engaged closely enough with the image to notice these elements. More concerned with Kollwitz’s subject matter in general and how it relates to the context in which the artist lived and worked, the art historian appreciated this new insight and resolved to be more attentive in the future to the object itself.

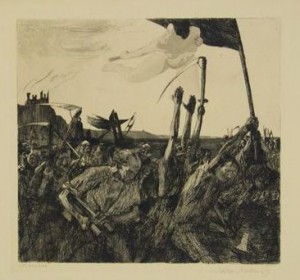

Uprising (1902-03, etching on heavy beige wove paper, 20¼″ x 23⅜″ [51.4 x 59.4 cm]). Plate 5 from the cycle Peasant War. From the 1908 edition of approximately 300 impressions. Knesebeck 70/VIIIb. Private collection. Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY. Familiar with most of Kollwitz’s oeuvre, this knowledgeable viewer knew that Raped was the second plate of seven in the print cycle Peasant War, commissioned by the Association for Historical Art in Germany following submission for consideration of the first completed etching of the series, Uprising (originally called Outbreak).2 In that print, a powerful woman, Black Anna, leads a contingent of fellow peasants armed with makeshift weapons against their feudal lords.3

Revolt (1899, etching on heavy cream wove paper, 11⅝” x 12½” [29.5 x 31.8 cm]). First concept for plate 5 (Knesebeck 70) from the cycle Peasant War. Knesebeck 46/V. Private collection. Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY. The idea for the cycle began in 1899 with a plate Kollwitz etched, variously translated as Uprising and Revolt, that pictured a rag-tag but triumphant mob of scythe-wielding farmers accompanied by a nude woman flying above, carrying a torch from which a flame leaps into the distant background to set ablaze the manor house, home of the oppressors. Coming from a long line of socialists, 4 Kollwitz had already explored the topic a few years earlier in her gold-medal-winning first cycle, A Weaver’s Rebellion.

From childhood, when the young Käthe had enacted barricade scenes with her father and brother, she had imagined herself a revolutionary. It followed that as an artist she would draw strong women into her narratives, depicting them as they sharpened scythes, galvanized men into action, cared for the wounded and identified the dead. When Kollwitz read Wilhelm Zimmermann’s 1841 General History of the Great Peasants’ War and discovered Black Anna, an actual participant in the 1525 revolt by peasants against their overseers, the idea for this cycle was born.

Answering the tourist’s questions about Kollwitz’s choice of printmaking, the art historian explained that after struggling unsuccessfully to master color in her studies at a Berlin academy for women and later in a painter’s studio, and being introduced in 1884 to the work of master printmaker Max Klinger, the young artist finally gave up on painting and in 1890 took up etching, a technique at which she soon excelled. Although Kollwitz later devoted herself to the medium of sculpture, in which she modeled emotionally compelling figurative pieces, she never abandoned printmaking. Expanding her practice to include lithographs and woodcuts, she valued the reproductive capabilities inherent in these mediums, guaranteeing the widest possible audience for her socio-political ideas.

The composition of Raped differs markedly from Kollwitz’s usual images of women who are shown in active roles, not supine on the ground. It is also the only instance where she tackled landscape with enough details to identify cabbage leaves, sunflowers and other plants.5 As for its narrative, in correspondence about this print the artist referred to Raped as “the next to the last plate,” which would have made it the sixth out of seven (though it was published as Plate 2) and described it as “an abducted woman, who after the devastation of her cottage is left lying in the herb garden, while her child, who had run away, looks over the fence.”6

Knowing the artist’s intentions and how she came to etch Raped served only to whet the tourist’s appetite for more information. Just then someone else approached, walking directly up to the two viewers who were blocking access to the print. As chance would have it, the latest arrival turned out to be a psychotherapist who worked with trauma survivors and had a long-standing interest in art depicting sexual abuse and other forms of personal violence.

Käthe Kollwitz, whose work is permeated with meditations on struggle and death, naturally aroused the psychotherapist’s curiosity, especially with respect to how the artist came to focus on those themes. Joining the already in-progress discussion, the clinician related how the printmaker’s son, Hans, had nagged his mother into writing about her life and her development as an artist, and how despite her initial objections, she had surprised him with a manuscript in 1922 that he later augmented with diary entries and letters, and published in 1955.7 Hearing what had already been learned by exploring the image and its creation, the therapist added to the discourse aspects of Kollwitz’s psychosocial history crucial to understanding her choice of subject matter for the etching.8

In recounting her early years, Kollwitz described seeing a photo of her stoic mother holding her firstborn son, “‘the holy child,’” who had died within a year of his birth. Her mother lost a second son before Kollwitz’s older brother Konrad was born. When Käthe was nine, her mother had Benjamin, who also failed to survive beyond his first year, dying from the same meningitis that took the firstborn.

The artist remembered how one night, during her baby brother’s illness, the nurse had burst into the kitchen where her mother was dishing out soup and yelled that the infant was throwing up again. Her mother had stiffened and then went on serving dinner, her refusal to cry in front of her family failing to conceal her suffering from her young daughter, to whom it was obvious.

After that dinner, Käthe–with her younger sister Lise–was sent to play in the nursery where she built with her blocks a temple to Venus and began preparing a sacrifice to a goddess she had learned about in a book on mythology, and who she had chosen to worship over the Christian “Lord”–a stranger to her despite her family’s devotion to him. When her parents walked into the room to convey the bad news that her little brother had died, Käthe was certain “God had taken him” as punishment for her disbelief and sacrifice to Venus.

Because the family’s way was to grit teeth and carry on, with no discussion or even expression of loss and grief, Käthe carried the burden of guilt for her brother’s death into her adult years. Her mother’s unexpressed sorrow suffused their home and her oldest daughter lived in fear that her parents would come to harm.

Stopping the story at that point, the psychotherapist retrieved an ebook reader from a handbag and read from Kollwitz’s autobiography. “I was always afraid [my mother] would come to some harm…If she were bathing…I feared she would drown.” Reflecting on watching through the apartment window as her mother walked by, Kollwitz continued, “I felt the oppressive fear in my heart that she might get lost and never find her way back to us…I became afraid Mother might go mad.”

As the clinician tucked away the ebook reader, the trio of observers turned back to the etching Raped. Suddenly they understood what the artist might not have known herself, that the young girl looking over the fence was nine-year-old Käthe and the woman on the ground was her mother, finally felled by a trauma too insistent to be repelled.

As the three viewers continued contemplating the poignant image before them, another person approached. They eagerly began sharing their recent discoveries as they made room for the newcomer who, noticing the dates of the artist’s life, explained that Käthe Kollwitz was not a twentieth century artist but a woman born, raised and educated in the second half of the nineteenth century.9 Living in Germany in the late 1800s must have affected her art, they all agreed.

But that’s a story for another time.

____________________________________________________

1A print of the etching was displayed for a while in the Drawing and Print Gallery of The Metropolitan Museum of Art several years ago. The work under consideration, a proof, is in the private collection of the writer.

2Martha Kearns, Käthe Kollwitz: Woman and Artist (New York: The Feminist Press at The City University of New York, 1976), 85.

3See Elizabeth Prelinger, Käthe Kollwitz (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 30-39, for a description of the evolution and content of The Peasant War cycle.

4See Jane Kallir, “Käthe Kollwitz: The Complete Print Cycles” (Galerie St. Etienne, exhibit essay, October 8 through December 28, 2013) for additional information about Kollwitz’s print cycles.

5 Hildegard Bachert, “Käthe Kollwitz: The Complete Print Cycles,” gallery talk (Galerie St. Etienne, November 7, 2013).

6Käthe Kollwitz, quoted in Käthe Kollwitz: Werkverzeichnis der Graphik, by Alexandra von dem Knesebeck, trans. James Hofmaier (Bern: Verlag Kornfeld, 2002), 291. Relevant excerpt of text included in provenance documents accompanying the proof.

7The Diary and Letters of Kaethe Kollwitz, ed. Hans Kollwitz, trans. Richard and Clara Winston (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1955).

8See Ibid., 18-20, for information about Kollwitz’s childhood experiences of loss.

9Bachert, gallery talk.

Käthe Kollwitz: The Complete Print Cycles

The Galerie St. Etienne

24 West 57th Street

New York, NY 10019

(212)245-6734

Now till December 28, 2013.

Posted in Art Historical Musings, Art Reviews |

Print This Post Print This Post

October 17th, 2013

A Case Study of

Psychoanalysis as an

Art Historical Method

Turn-of-the-nineteenth century Vienna was a fertile time for scientists, intellectuals and artists as the planets aligned to create what has been called “The Age of Insight.” The mind became an object of intense scrutiny for practitioners of medicine, psychiatry, psychology, and the literary and visual arts. New methods that were developed in pursuit of understanding human nature from a biological perspective found usefulness in the study of art and artists.

One resident of the city, Sigmund Freud, created a system of indirect investigation into the psyche using personal experiences like dreams, fantasies, slips of the tongue, and artistic productions. Calling his method psychoanalysis and taking it beyond the confines of his medical practice, Freud applied it everywhere without reservation, writing about jokes and everyday missteps, romance and war, and creativity and art.

Ever curious about Italy and its artists, Freud wrote a book-length analysis of Leonardo da Vinci based on a memory the artist had included in his Codus Atlanticus. In Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood, the doctor uses psychoanalysis with great conviction to answer intriguing questions about this Renaissance master and scientist.

The first German edition of the book, published in 1910, was followed by four more (1919, 1923, 1925 and 1943). An English translation titled simply Leonardo da Vinci appeared in 1916, followed by an additional two (1922 and 1932) before the one under consideration here. In 1964 Alan Tyson, working under the general editorship of James Strachey with Anna Freud and Alix Strachey for The Standard Edition, translated the text with an expanded title for this first American edition.

In his book-length essay, Freud takes as his starting point Leonardo’s description of an event from his childhood, using a flawed German translation of the original Italian, to understand why Leonardo traded art for other inventions and took off in pursuit of scientific knowledge. In typical Freud writing style, the psychoanalyst anticipates all manner of resistance throughout the piece, beginning by assuring those who would question his motives that his intentions are not “‘[t]o blacken the radiant and drag the sublime into the dust’” but rather to further understand a man that he referred to as “among the greatest of the human race.”

Before he tackles the childhood memory, Freud describes Leonardo’s struggles with his art, beginning with the perfectionism that made each painting a major endeavor of upwards of several years and left more than a few unfinished. He cites Vasari and later art historians who quote Leonardo’s contemporaries on the subject, and mentions several specific paintings as examples, including the Last Supper, where the artist’s frustration with the rapid execution required of fresco painting resulted in the technical disaster that has challenged conservationists ever since.

From there Freud begins an elaboration of Leonardo’s personality based on observations by those who knew him in some way, maneuvering closer to his primary thesis by proposing that the artist “represented the cool repudiation of sexuality.” He finds evidence for this in Leonardo’s own words as quoted by Edmondo Solmi, an Italian philosopher of Freud’s time. Soon enough the psychiatrist addresses Leonardo’s homosexuality, declaring that even though the fledgling artist had gotten into trouble with the law for it when he was in Verrocchio’s studio and surrounded himself with beautiful young boys once he was a master, for sure he never actually engaged in sexual activity.

In another secondary source, Freud finds Leonardo averring that “[o]ne has no right to love or hate anything if one has not acquired a thorough knowledge of its nature.” Applying that to the artist’s assumed abstinence, he notes that in this case “[t]he postponement of loving until full knowledge is acquired ends in a substitution of the latter for the former.” Thus, for Leonardo, investigating took the place of creating art and of producing much of anything else.

In his element now, Freud asserts that around age three most children go through a period of “infantile sexual researches” usually precipitated by the advent of a new sibling, which invites the question: whence babies? When repression puts an end to this phase, various outcomes are possible. Freud believed that Leonardo’s unconscious resolution was perfect; by channeling his sexual drive into non-practicing homosexuality and allowing his investigative instinct to reign supreme, the artist-scientist avoided a neurotic resolution, freeing his libido to “act in the service of [his] intellectual interests.”

After establishing this psychoanalytic foundation, Freud provides information about Leonardo’s childhood, noting that the artist was illegitimate, initially lived with his mother, and when five years old went to live with his father, who had recently married. That these inadequate bits of biographical data are poor substitutes for having the analysand before him doesn’t seem to deter the doctor from basing his conclusions on them.

Finally Freud presents the memory, translated for this book from the German text he quotes, Marie Herzfeld’s translation of the Italian original as it appeared in Nino Smiraglia-Scognamiglio’s edition of the Codex Atlanticus. Her version erroneously rendered nibio as vulture when in fact it means kite, a much smaller, non-carrion-eating raptor with the ability to hover in the air due to its long, forked tail. She also omitted dentro (within), which alters the action of the all-important tail. These changes have been indicated in brackets in the rendering of Leonardo’s words that follows.

It seems that I was always destined to be so deeply concerned with vultures [kites]; for I recall as one of my very earliest memories that while I was in my cradle a vulture [kite] came down to me, and opened my mouth with its tail, and struck me many times with its tail against [within] my lips.

After extolling the virtues of psychoanalysis as a tool for deciphering this passage, Freud points to the obvious erotic content, noting that “tail” (coda in Italian) is a common slang term for penis. He then goes on to construct an interpretation of the memory that defies Occam’s razor.

Although he acknowledges the similarity between Leonardo’s memory and the dreams and fantasies of women and passive homosexuals, Freud opts to see it as a symbolic representation of the baby suckling at its mother’s breast. He supports this hypothesis by pointing out that in Egyptian mythology a mother goddess, whose name was Mut (similar to the German mutter for mother), was pictured with a vulture’s head, adding that at the time all vultures were believed to be female.

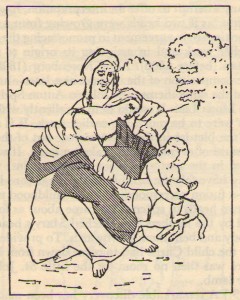

Freud concludes that the memory represents the overdependence on, and eroticization of, Leonardo by his mother, who used him when he was quite young as a substitute for his missing father. In the rest of the essay, Freud looks first for confirmation of his ideas to Leonardo’s art–in the special smiles that grace the faces of his women and in The Virgin and Child with St. Anne, with its hidden vulture.

As further support, the psychoanalyst pulls in his theories on infantile sexuality, the phallic mother, homosexuality and the Oedipal complex. He finds indirect evidence in Leonardo’s writings for a negative relationship with his father, linking it to the artist’s homosexuality and his rejection of religion. Freud even finds meaning in Leonardo’s obsession with flying machines, citing the connection between dreams of flying and sexual performance.

In the final chapter of the book, feigning humility, Freud addresses possible objections to his “pathographical review of a great man,” admitting the limitations of applying psychoanalysis to the biography of someone about whose early life so little is known. He nonetheless confidently asserts that he has accomplished what he set out to do, showing how the circumstances of Leonardo’s childhood, combined with his inherent capacity to repress and sublimate his primitive instincts, resulted in a celibate artist-scientist forever torn between his art and science. Although Freud was well satisfied with his conclusions, their unfavorable reception seems to have discouraged him from tackling other art historical subjects.

Freud came to this particular project via a long-standing interest in Leonardo–once remarking in a letter to his friend Wilhelm Fliess on the artist’s celibacy and left-handedness–and had read Dmitry Sergeyevich Merezhkovsky’s historical novel, Leonardo da Vinci, which he cites in the text as though it were a historical document. His other bibliographical resources include volumes written on Leonardo by an assortment of scholars as well as a long list of his own publications.

Not unlike Leonardo, Freud was enticed away from his original career path by his curiosity. Born in Moravia in 1856 but resident in Vienna from age three until he fled Austria for London in 1938, Freud studied biology and medicine, qualifying as a doctor in 1882. Three years later, a trip to the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris and time spent with the celebrated expert on hysteria, Jean-Martin Charcot, changed his professional direction from clinical neurology to medical psychology. With his Interpretation of Dreams, published in 1900, Freud moved even further away from the laboratory, confining his research to observations of his psychiatric patients and reflections on his own experiences and psyche. Out of that work, he developed the practice of psychoanalysis and his theories about the unconscious.

When he decided to pursue an analysis of Leonardo da Vinci, Freud turned to writings by prominent art historians, among them the German Jean Paul Richter (1847-1937) and the Frenchman Eugène Müntz (1845-1902), whose methods happened to be at odds with each other. Richter, a disciple of Giovanni Morelli (who believed art was best studied by looking at objects with a well-practiced scientific eye), published in 1883 The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci, a two-volume work, first in Italian, then German and English, the last of which Freud consulted. Müntz, on the other hand, believed in the importance of archival research and, opposing Morelli’s focus on connoisseurship, based his studies on documents he unearthed in Italian archives. His monograph Léonard de Vinci, released in 1899, was one of Freud’s references.

If the psychoanalyst was aware of the caldron of ideas that simmered close by, especially in the Vienna School but also elsewhere, about how best the discipline of art history should be practiced, his bibliography doesn’t reflect it. The ideological stew included empiricists who looked to science as a model for the investigation of artworks as physical entities in documented contexts, philosophers who approached the study of art from a metaphysical perspective–more concerned with ideas than things, and a new breed of cultural historians, who occupied a middle ground between the two, finding value in each and adding ethnography and psychology to the mix.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin and Child with St. Anne (c. 1508, oil on wood, 66″ x 44″ [168 x 112 cm]). Musée du Louvre, Paris. [

Sketch of The Virgin and Child with St. Anne from Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of his Childhood, page 66. Freud seems to have gravitated toward outliers like Walter Pater (1839-1894), a British aesthete whose Studies in the History of the Renaissance, a collection of essays published in 1873, had to be recalled because of their anti-religious nature. In his discussion of specific artwork by Leonardo, the analyst relied on those essays plus the work of two others: Oskar Pfister (1873-1956), a Swedish minister with an interest in philosophy and psychology with whom Freud maintained regular correspondence for many years, and whose discovery of a vulture in The Virgin and Child with St. Anne provided critical evidence for the hypothesis expounded in the book; and German-born Richard Muther (1860-1909), an emotionally expressive writer whose description of images tended toward the “lurid and erotic.” In fact, Freud’s insufficient knowledge of art history and the scholarship on Leonardo made mistakes inevitable and stood in the way of producing “a meaningful art historical essay on the artist.”

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa (1503-17, oil on poplar, 30″ x 21″ [77 x 53 cm]). Musée du Louvre, Paris. Freud referred to the more mainstream writers earlier in the book when introducing Leonardo, his practices and milieu, but switched over to the others later on when analyzing the latent meaning he espied in the artist’s words and images. For the Mona Lisa, he liked Pater’s perception that it contained “a presence…expressive of what…men had come to desire…the unfathomable smile, always with a touch of something sinister in it, which plays over all Leonardo’s work.” And he turned to Muther for observations on the physical relationship among the mothers and baby, and St. Anne’s perpetual youth in The Virgin and Child with St. Anne.

Because his interest was primarily psychological, Freud could be expected to seek out those who approached the study of art from a similar perspective. While there is surely much to be gained through the understanding of artists’ intrapsychic development and interpersonal relationships, Freud’s system of thought–psychoanalysis–contains many flaws, not the least of which is his attribution of adult sexual feelings to infants and children.

In explaining Leonardo’s memory, the doctor first must explain how the vulture’s tail comes to be symbolic of the artist’s intense erotic attachment to his mother and how that desire later morphs into homosexuality. He does this by invoking the phallic mother who is imagined to possess a penis by the little boy appalled at the thought that someone he loves so dearly should lack such a precious appendage. This intense mother-son bond is reinforced by Leonardo’s oversolicitous mother and absent father, and the child’s unconscious identification with the idolized mother. The boy grows up to be a man who love boys in the same way his mother loved him. Here Freud confuses homosexuals with pedophiles; the former are attracted to other men while the latter prey on vulnerable children.

Because Freud’s reasoning about such Leonardo mysteries as his perfectionism, depiction of smiling women, and turn from art to scientific research depends so heavily on the Oedipus complex and other aspects of his theory of infantile sexuality, it’s important to know how he came to substitute those assumptions for his empirically based seduction theory of hysteria.