Art Historical Musings

Print This Post

Sunday, July 9th, 2017 Print This Post

Sunday, July 9th, 2017

Possessing Strangeness:

Don Fernando Enríquez Afán de Ribera

and Jusepe de Ribera’s Bearded Lady

[To view the slide show in a separate tab, place the mouse pointer over the first slide, right click, select <This Frame>, then <Open Frame in New Tab>.]

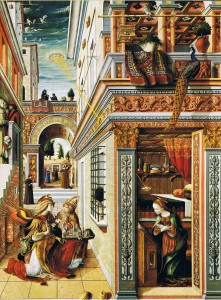

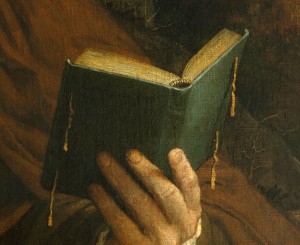

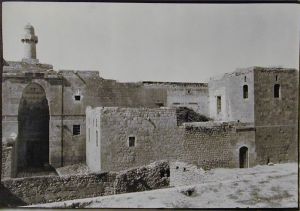

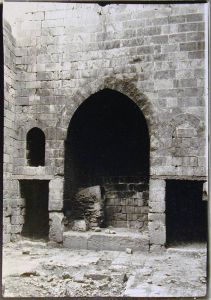

A most unusual painting (Fig. 1) hung among the portraits, landscapes and religious scenes decorating the walls of the room in the Casa de Pilatos (Fig. 2) where the Third Duke of Alcalá–don Fernando Enríquez Afán de Ribera–took meals with his family. Commissioned in 1631 and completed by February 11 of that year (though dated several weeks later), Jusepe de Ribera’s Magdalena Ventura with Husband and Child (The Bearded Woman) was hailed at the time of its creation by the Venetian ambassador to the royal court in Naples as “[…] a thing of wonder.”

Over six feet high, the startling image of what looks like a man in women’s clothing with a perfectly spherical bared breast, must have been an imposing presence in the palace dining room. Centrally located on the canvas, the object of wonder is flanked in the background shadows on her right by her husband, who turns his head slightly to look at his wife. With wide-open eyes, brows arched upwards and pulled together, arms pressed against his body, shoulders raised ever so slightly, he fidgets with his hat. Ribera, a master in portraying emotion through gesture and facial expression, here conveys a man’s apprehension about his wife as a target for the penetrating gaze of an artist.

Magdalena Ventura, with the raised, pushed out lower lip and knitted brows of angry contempt, resolutely looks straight ahead at the viewer. Broad-shouldered, symmetrical and echoing the impassivity of the nearby stone, she cradles her infant in large, masculine hands. The baby, swaddled in an orange-red blanket with white edging, looks impassively upwards, taking no notice of the proffered breast that looms over it. The three are posed in an undefined space devoid of furnishings, presented to the collector as specimens ready to be arranged among other, similar types of curiosities.

Magdalena’s lace-trimmed white apron and collar, the ring on her left forefinger and the decorative ornament on the child’s bonnet suggest the couple was of some means. This implausible-but-real family originated in a town in the Abruzzi, part of the viceroyalty of Naples, and according to the inscription on the stele pictured on the far right of the painting, moved to the capital city when Magdalena was fifty-two. As the story went, she suffered from a malady–peculiar to the southern latitudes–of excessive hair growth, which began for her at the age of thirty-seven and included the flourishing of a luxuriant black beard.

Having somehow learned of the proximity of this human rarity, Don Fernando went about acquiring her for his collection in the only way possible. He had her image captured on canvas. For his personal viewing, he placed her in one of the least public spaces in his palace in Seville, perhaps an indication of his attachment to the portrait and/or simply for the sake of propriety. Judging from many of the items listed in the 1637 inventory made after his death, the duke was quite fond of oddities of all kinds. In fact, a good case can be made for his having conceptualized his entire Casa de Pilatos as a cabinet of curiosities (Wünderkammer)–a setting where naturalia and artificialia could be flaunted. Possessing the hirsute mother of three must have been quite a triumph for him and perhaps the envy of his peers.

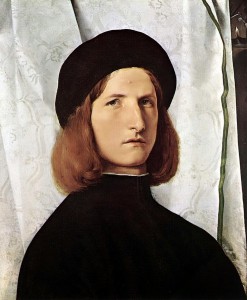

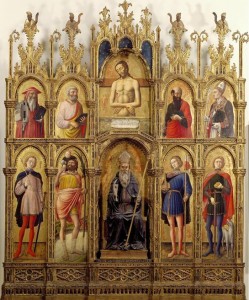

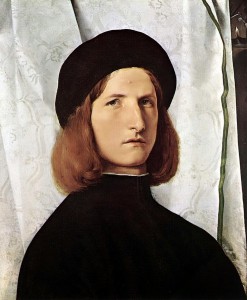

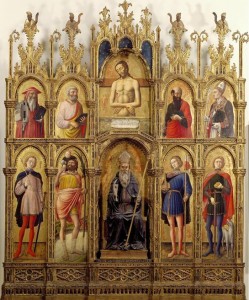

Both the subject of the painting and the duke’s collecting habits indicate his awareness of the proper pursuits for a man of his station. Born into a noble Sevillian family in 1583, the son of Fernando Enríquez de Ribera–a man who took for his own mentor Francisco de Medina, one of the great humanist scholars of the time, Don Fernando Third Duke of Alcalá (Fig. 3) could count in his ancestry the first kings of Castile and Leon. Left fatherless at the age of seven, the duke received an education reflective of that heritage and his father’s immersion in intellectual, literary and aesthetic pursuits.

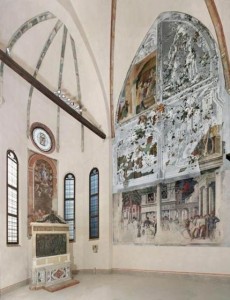

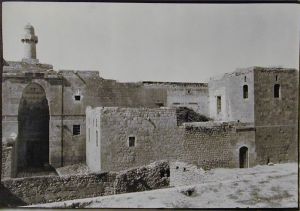

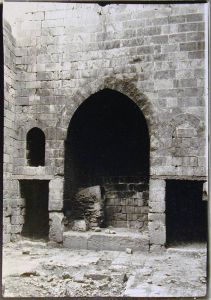

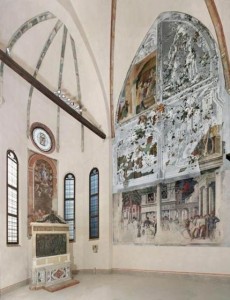

His home, the Casa de Pilatos (Figs. 4 and 5), had its own grand history. Created in the late fifteenth century by the first Marquis of Tarifa Fadrique Enríquez de Ribera, stocked at its inception with books, paintings, tapestries, and souvenirs of the earliest inhabitant’s travels, the palace hosted as well the collection of antique sculpture and inscribed stones purchased by the Third Duke’s great-uncle Pedro Enríquez y Afán de Ribera during his tenure as viceroy of Naples (1559-71).

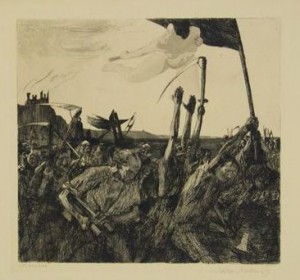

Following in the steps of his forebears, the Third Duke sought service to his king, Philip III, though not without encountering self-erected stumbling blocks along the way. Having lost his father early on and then four years later his grandfather (the First Duke of Alcalá), Fernando came into his inheritance of wealth and responsibilities before he was twenty, at which time he had already been married for four years. In exercising one of those hereditary duties, that of constable of Seville, he found himself brought up on charges of abuse. Two years later, he was again in trouble, facing steep fines after his servants assaulted a municipal officer whose lack of sufficient deference to Alcalá triggered the violent reaction.

Not surprising then that it was a while before Don Fernando earned his first major royal appointment, that of Viceroy to Catalonia in 1618, where his lack of political acumen made him a poor representative of the crown. After overseeing for three years a friction-plagued administration, he was recalled. In a 1622 letter, he described how the misery of his time in Barcelona had been relieved by the chance to look at art and examine manuscripts, and by little else.

Schooled in Latin, logic, philosophy and theology as a teenager, the young Alcalá demonstrated a keen interest in the liberal arts, learning to write music and play the guitar, and to draw and paint. It was documented that he was especially adept in coloring and though little by his hand has survived, the sketches that do–of archaeological subjects–testify to the accuracy of the reports. His easel of diverse inlaid woods, whether or not acquired at the outset of his artistic activities, was later kept in the camarín grande, a large space frequented by many visitors. The easel painted its user as a member of a special class of “cultivated Baroque gentleman” who participated actively in the study and practice of the liberal arts.

Don Fernando’s career as a connoisseur began in those early years, as did his role as sponsor of an Academy where Sevillian scholars and other intellectuals met to discuss literature and the arts. Common among the nobility throughout Spain, these gatherings were not formally organized like their counterparts in Italy and France. Instituted by his grandfather in 1589 and attended by Fernando despite his tender age, it met in the camarín grande–the gallery built by the First Duke to display antiquities, and later expanded by the Third Duke to accommodate his collection of small ancient and contemporary bronzes, classical busts, urns and an assortment of other objects that would come over time to constitute a major section of his cabinet of curiosities. Large enough to accommodate the four thousand books accumulated by the First Duke, which were later augmented by Don Fernando with a single purchase of another five thousand, a library that large would have been quite a resource for the visiting discussants.

Esteemed as “[…] one of the most cultivated nobles in Spain” by no less than Francisco Pacheco (author of Arte de la pintura and father-in-law to Diego Velázquez), Alcalá invested the good fortune of his inheritance in his palace, initiating in 1603 much needed repairs, along with new construction. As part of the renovation, Pacheco–Alcalá’s friend, advisor and artist–executed paintings for the ceilings (Figs. 6 and 7), the centerpiece of one of which was The Apotheosis of Hercules (1604, Fig. 8), designed to provide direction for a nobleman in need of a virtuous path.

The most noteworthy architectural additions (Figs. 4 and 5), the set of rooms on the upper floor between the patio overlooking the courtyard and the Jardín Grande (large garden), provided room for the duke’s collections to grow. Included here were the library and armory, reception room and cabinet of paintings–all essential ingredients for any Wünderkammer. Undoubtedly aware of the marvelous Sevillian museum of Gonzalo Argote de Molina (Pacheco authored that earlier collector’s biography), Alcalá might have felt both inspired by, and challenged to compete with, his compatriot.

Though relatively modest, Argote’s assemblage, begun in the middle of the sixteenth century and lasting till its dispersion sometime before 1586, was noteworthy for its stable of fine horses, armory filled with arms old and new, library of rare books, picture gallery of mythological scenes, and portraits commissioned from Alonso Sánchez Coello (Philip II’s painter). He also laid out within his cabinet a stash of stones, coins, antique gems, and what seemed to be a natural history museum of taxidermic animal heads and birds.

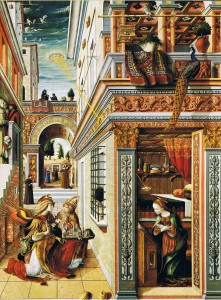

A major afficionado of hunting, Argote penned a book on the subject that included a description of the picture gallery in the royal hunting lodge, the Pardo Palace, taking note of what he called its “wonders of nature.” One of the objects within that category, a bearded woman by Antonis Mor, probably perished in the blaze that destroyed much of the place in 1604. Mor’s painting might have been known to Juan Sánchez Cotán (the Spanish still-life painter), whose Brígida del Río, la barbuda de Peñaranda (1560, Fig. 9) depicted a well-known curiosity of the late sixteenth century.

An experienced and accomplished collector like the Duke of Alcalá would have surely been familiar with the stories and accompanying pictures of the bearded woman of Peñaranda and with the Mor painting in the Pardo. An avid devotee of the strange, he would eventually commission his own version of the subject for the Casa de Pilatos, where it joined many, mostly art-related, objects later listed in an inventory drawn up in advance of the estate sale to be held in Genoa. The document catalogued the contents of the nine major areas of the house, including those in the camarín grande–the location of some eye-catching items.

Exemplary of a cabinet of curiosities, objects present in that scholarly arena embodied the zeitgeist of the seventeenth century, when the opening of trade routes to the transatlantic west and exotic Far East brought novel products of human and natural design to Spain, Italy and elsewhere, enticing those with the inclination and means to attempt to possess the world in a room. That seems to have been what Don Fernando sought to accomplish when he accrued during his travels unusual objects like feather pictures from the “Yndias” (Spanish colonies in the New World), a package (or quiver) of Indian arrows, an ivory horn in one piece (Fig. 10), an astronomical ring–perhaps an astrolabe (Figs. 11 and 12), glass vessels believed to have been used by the ancients to store the tears of mourners (Fig. 13), a nail from the Pantheon portico in Rome, two thin branches and a flask of water from the Jordan River, an iron tool for opening bars/grills, a large gunpowder horn (Fig. 14), and many spherical pieces (marbles come to mind) of agate, amethyst and different colored jasper, and so on and on.

The potential for acquiring such curiosities increased considerably when the Third Duke of Alcalá returned to the royal court in Madrid in late 1624. With a new king, Philip IV, a new and anti-Spanish pope, Urban VIII (née Maffeo Barberini), an existing vacancy for an ambassador to secure diplomatic relations between Spain and the Vatican, and the recommendation of the royal favorite Count-Duke of Olivares, Alcalá was sent to Rome in hopes that his intellectual prowess would impress the similarly endowed pontiff. The Third Duke was in Rome by the summer of 1625, making a favorable impression on Urban VIII, but not enough of one to fulfill his charge to win over the pope to Spain’s agenda. It wasn’t until 1629, therefore, that Olivares and Philip IV saw fit to grant the duke another assignment. When they did, it was to replace the Duke of Alba as Viceroy of Naples.

Naples was not unknown to Don Fernando. There–the third stop on his 1626 tour of Italy that began with Genoa and Venice during the year of his ambassadorship–he acquired what was perhaps his first painting by Ribera. Securely identified from documentation as Christ Being Prepared for the Cross (ca. 1626, Fig. 15), in the 1637 inventory it merited an unusually lengthy description, signaling the importance of this canvas by the hand of “R[iber] Valenc[ian]” to at least the auditor if not the late Alcalá himself. Perhaps its singularity related to its having been a diplomatic gift from the Duke of Alba, Viceroy of Naples from 1622-29 and eventual nemesis of Don Fernando.

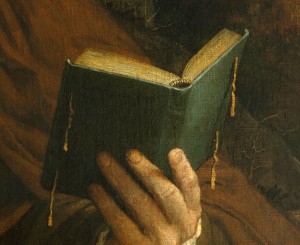

Hanging in the small chapel of the Casa de Pilatos–the first of the nine main sections described in the death inventory, Christ Being Prepared for the Cross belonged to a category of work for which Ribera had developed a reputation: paintings small enough to be conveniently moved, and hence perfect for private collections and chapels. Another line of the artist’s production–compositions of half-length saints, apostles and secular notables with their relevant accessories, in undefined, tenebristic spaces (Figs. 16 and 17)–apparently also served well Don Fernando’s program of decoration for his palace, part of which was the theme of beggar philosopher, fitting for the erudito the duke styled himself to be. Numbering eight in all, four were commissioned from Ribera and hung in pairs in different rooms of the house (Figs. 18 and 19).

Analogously, when Alcalá considered securing a bearded lady for his Wünderkammer, he turned to Ribera, an artist known for his commitment to drawing and painting from life, and for his depictions of oddities like grotesques, and narratives of extreme human behavior. Surely this collector and artist were meant for each. Don Fernando’s “[…] interest in unusual human behavior” was noted by Brown and Kagan in their introduction to the 1637 inventory when they singled out a painting attributed to Alcalá’s private painter Diego de Rómulo of “[…] the ‘portrait of the buffoon who eats everything that is painted on his plate’ [iv. 23].”

Rómulo’s painting hung in the fourth room of the palace (as divided in the inventory), keeping company with a Gianbologna three-horned bull (probably a rhinoceros), landscapes, Venetian portraits, still lifes (another passion of Alcalá’s), a few saints, two more philosophers, a Gianbologna bronze on a mahogany table, and other furniture and sculpture. In the fifth room, where the duke ate, Ribera’s Bearded Woman held court with a large painting of a butcher shop and a canvas of Herod with the Head of Saint John the Baptist. Joining them in the dining room were–among others–pictures of religious subjects, paintings with attributions to Palma il Giovane and Albrecht Dürer, landscapes of ruins (reminders to Don Fernando of his visits to archaeological sites in Rome), portraits of emperors and a bare-breasted Venetian woman holding a bouquet of herbs, perhaps Flora.

Truly an eclectic selection, the contents of these rooms continued Don Fernando’s decorative agenda throughout the house into more private spaces, echoing the cabinets of curiosities of other Spanish nobles, who in their grand galleries brought together paintings, objets d’art, wonders of nature and marvels of human craft. These Wünderkammers, often indistinguishable from Kunstkammers, could grow to huge proportions and encompass a high degree of variety (Fig. 20).

A compendium of many of the grandest ones appeared in Vincente Carducho’s 1633 Diálogos de la Pintura, though it made no reference to Alcalá’s. Nonetheless, the kinds of objects encountered during the chronicler’s visits to these treasure troves were identical to many in the Third Duke’s death inventory.

The Wünderkammers Carducho did document could contain upwards of a thousand or more paintings within which were found some by great masters like Titian, Raphael, Leonardo and Bassano–all of whom were represented on select walls of Alcalá’s house along with notable artists Artemisia Gentileschi, Velázquez, Dűrer, Guido Reni, Perugino and Michelangelo, many in room three of the Casa de Pilatos, the corridor with the door to the loggia overlooking the garden. Two of Ribera’s philosophers (Figs. 16 and 17) lived there, too.

Other items Carducho encountered were sculptures, swords, knives, shields, carved and engraved rock crystals and ivory, escritoires and buffets, balls of jasper, clocks, mirrors, globes, spheres, relics, and mathematical and geometrical instruments. Versions of all of these once filled the galleries and gardens of the Casa de Pilatos, where objects proclaimed their fine craftsmanship, exotic origin, rarity, variegated mediums and materials, antiquity, and natural origins–all characteristic of a cabinet of curiosities.

In addition to the rooms already described, a small, private space adjoining the dining room–noteworthy for its maps–was followed by a seventh room described as small, “where the duke received visitors.” Within its walls sixty-two objects, many of high quality, vied for visitors’ attention. Catalogued were paintings like that identified by Pacheco as a famous one by Tintoretto, a large canvas by Andrea del Sarto (Fig. 21), a group of fourteen still lifes in golden frames, and a portrait of a cleric by Leonardo. Here, too, were quite a few desks, some of ebony and walnut (Fig. 22), sculptures of bronze, marble and black stone, several chairs and mirrors, and a cherry-wood box for chess pieces by then missing.

In this intimate space overlooking the garden–which functioned as a portal to the Casa de Pilatos, Don Fernando crammed an impressive selection of objects, again showcasing for visitors a pair of Ribera philosophers (Figs. 18 and 19). From here, the duke could guide his guests into his camerín grande where they would be greeted by souvenirs from his travels, scientific instruments, his collection of small bronzes–many by Gianbologna, eighteen pictures on paper of animals by Bassano, nine paintings of muses by Alonso Vázquez, a portfolio of prints and drawings (unfortunately none specified), a self-portrait of Titian and a copy of his Danaë, and so much more, adding up to a dizzying array of two hundred and fourteen fabulous objects.

From the small chapel filled with devotional images and the dining room with Ribera’s Bearded Lady, to chambers filled with paintings, sculptures and decorative objects, reaching a crescendo in the camerín grande with its mix of naturalia and artificialia, the Casa de Pilatos epitomized a seventeenth-century Wünderkammer. While the inventory says nothing about the manner in which the small exotic objects were displayed, by virtue of their inclusion among such illustrious pieces as old master paintings and bronze sculptures, curiosities like the nails from the Pantheon must have been shown in a way that communicated their value to the auditor, who made sure to inscribe them in the inventory. How exactly Don Fernando managed that, how he placed each piece within its respective room–in conversation with what other item–remains as yet and perhaps forever unknown. Perchance some yet undiscovered print or painting of the interior of a Spanish Baroque gentleman’s palace will prove the key to the mysteries still locked away in the Third Duke of Alcalá’s Wünderkammer.

_______________

For citations and bibliography, contact the author at: deborahfeller@verizon.net

Posted in Art Historical Musings |

Print This Post

Thursday, August 25th, 2016 Print This Post

Thursday, August 25th, 2016

Courting the Contemporary

Art-Historical Museums Follow the Money

[To view the slide show in a separate tab, place the mouse pointer over the first slide, right click, select <This Frame>, then <Open Frame in New Tab>.]

Enjoying the centuries-old paintings in the gently-lit exhibit on Japanese collections at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the visitor entering the rooms at the hairpin curve of the u-shaped circuit of galleries was confronted with a narrow, lightly curved, soaring piece of gleaming white metal on a thin, highly-polished, black stone plinth (Slide 2, Fig. 1). In a space at the very end of her tour, contemporary paintings surrounded a glass sculpture of a deer (Slide 2, Fig. 2) affectionately called “Bubbles” because of its skin of varied-sized glass spheres.

Such incidents have become quite common in encyclopedic/universal art museums, where the primary focus on objects–from all over the world–with aesthetic and historic value has been slowly eroded by a pressing need to attract more people to guarantee enough income to keep this type of art venue alive. Even a frozen-in-time institution like The Morgan Library and Museum splashed a detail of an Andy Warhol book jacket–decorated with a couple of flirtatious nude angels–on the cover of its Calendar of Events: Winter & Spring 2016 (Slide 3, Fig. 3) to trumpet its upcoming exhibit, Warhol by the Book–a departure from its usual, more staid fare. In yet another incident of new art keeping company with old, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC situated Roy Lichtenstein’s classically toned painting Entablature on the wall above a quintessentially Canova reclining nude (Slide 3, Fig. 4).

Other manifestations of these contemporary times can be found on the websites of all museums–like that of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Slide 4, Fig. 5), where links to social media like Twitter and Facebook have become de rigueur, and redesigns of logos as part of rebranding campaigns–like the one undertaken by The Met in 2016 (Slide 4, Fig. 6)–attempt to alter perceptions by presenting a more with-it, though aesthetically flawed, veneer.

Museum education programs have morphed, too, into vehicles engineered to engage a more diverse audience. In the face of this increasing proliferation of contemporary art, new approaches have been developed to help museum goers deal with incomprehensible objects that baffle and irritate them. Traditional, information-based explanations have in some places yielded to Socratic questioning to elicit viewers’ responses to, and thoughts on, the art object.

When museums turn their spotlights on the contemporary in this way, they are responding to outside forces, primarily those of the marketplace. Since at least the late eighties, when artists began departing from ordinary means of expression, (painting, drawing, sculpture, even video) and embarking on experiments with largely conceptual and otherwise unusual materials, new art has been edging out its competition. Increased demand has turned contemporary art into big business, creating a veritable “asset class” of great interest not just to collectors but also to hedge fund managers, who buy low in quantity–driving up prices of little-known artists’ work–and then, after holding onto the objects for an average of two years, sell high–sometimes, in the process, flooding the market.

Growing numbers of collectors with major holdings of contemporary art, looking to place their work strategically–either through loans or outright donations, offer financial support to those institutions receptive to their artists. Art-historical museums like The Met can’t afford to ignore such a large pool of prospective patrons, but when they invite them and their cohorts–galleries, dealers and auction houses–into their hallowed halls, they risk practicing “checkbook art history.”

When an encyclopedic museum that has historically limited its holdings to that of the past, acquires an art object of a certain age, the effect on the artwork’s market value will be little affected by the positive regard thus bestowed. But when a piece created by a living artist enters a museum’s permanent collection, all of that artist’s production will increase in value, much to the advantage of the dealer/gallery who represents the artist and has sold it.

These and other dangers have not served as a deterrent to universal museums like The Met in New York–which plans to reconfigure and expand its current modern and contemporary wing, and in 2015 leased from the Whitney its vacated Breuer building (Slide 5, Fig. 7) to mount related exhibitions during that process–and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art (Slide 5, Fig. 8) in Arkansas–which announced in 2016 its intention to transform an old cheese factory into a display box for new art, explaining how it would become “one of the hottest destinations in the country” and be “huge for the younger generation, the millennials.” The Met, however, was later forced to put its well-underway program on indefinite hold due to financial troubles, some of which have been ascribed to the outpouring of funds needed to cover the refurbishing and staffing of its new annex.

For boosting numbers, such architectural add-ons are good bets. The results of a 2015 study found that “[m]useums that expanded between 2007 and 2014 saw their attendance rise significantly faster than museums that did not…,” although in time those gains became less dramatic.

This pressing need to bring in more visitors and hence more money originated in the early nineties when a stagnant economy forced the United States government to question its commitment to funding the arts. The Republican takeover of Congress in 1994 provided fertile ground for the culture wars that ensued, when politicians like the mayor of New York railed against the Brooklyn Museum of Art’s cutting-edge exhibit Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection (Slide 6, Fig. 9), and the Corcoran cancelled its upcoming retrospective of Robert Mapplethorpe, whose homoerotic photographs, bordering on the pornographic (Slide 6, Fig. 10), had the potential to trigger a defunding backlash from the federal government.

Other economic pressures have accrued to art museums in the ensuing years. Afficionados of contemporary art with large enough collections and deep enough pockets began at the beginning of the twenty-first century to build their own museums rather than target a favored museum as the final resting place for their beloved objects. The alternative to donations–purchasing art outright–has become less of an option for museums, whose acquisition budgets can’t keep up with prices like that of Amadeo Modigliani’s Recumbent Nude, which sold at auction for $170.4 million (Slide 7, Fig. 11).

In their desperate competition for limited funds, art museums today are trapped in a maelstrom of inexorable growth. Reduced government spending has led to greater reliance on corporate and individual funding, which requires museums to substantiate their worth with healthy attendance figures. Nothing does that quite so well as blockbuster exhibitions, whose increased costs call for even more individual donor support. To attract new patrons, museums have to appeal to their artistic tastes, now overwhelmingly contemporary, with reimagined and expanded old buildings and newly constructed minimalist ones that reflect their art.

Enlargement brings its own challenges. Growing to resemble major corporations, museums have to meet the demands of their metamorphosis by expanding existing departments like administration, visitor services, development and membership, creating new ones like media relations and establishing novel positions like that of chief digital officer–the holder of which at The Met commands a staff of seventy–all of which costs money. Increased overhead requires additional income, which calls for more fundraising efforts aimed at corporate sponsors and individual collectors, and forces museums to lure even more people through the door with ever more dramatic exhibitions for which new donors must be found, repeating the cycle ad nauseam.

These financial stresses have bred questionable practices. Nonprofit museums now extract payments, which they call donations, from galleries whose artists they show, requesting anywhere from $5,000 to $200,000 to help cover expenses. They might also squeeze them for referrals of potential donors. The larger the gallery, the more it can afford to cooperate, which apparently garners maximum benefits. Almost a third of major one-person exhibits in the US between 2007 and 2013 went to artists represented by just five galleries, with the figure staggeringly greater for contemporary art museums like the Guggenheim (ninety percent) and the Museum of Modern Art (forty-five percent), a cautionary statistic for art-historical museums that insist on playing in this league.

Artists already represented by big-name galleries become widely known and hence more popular, enticing museums to use as a criterion for inclusion the fame factor. In its press release about its Collectors Committee’s recent purchases, the National Gallery of Art proudly declared that it had acquired Janine Antoni’s chocolate-and-soap sculpted self-portraits, “Lick and Lather …, arguably her most famous work (Slide 8, Fig. 12).” [Italics added for emphasis.]

The statement highlights the elusive nature of defining the artistic value of mainly conceptual, contemporary art. Not only do curators find themselves in competition with sales-related departments like marketing and digital media services, but when they and other apologists for the new are asked to delineate criteria for it, they avoid answering the question.

Art seasoned by time can accrue value over the course of its existence simply by virtue of survival. Too, historical criteria for its quality and importance will have already been established. Not so with brand new works that have not been subjected to that test of time. An art that indiscriminately encompasses every self-defined work as art invites a leveling of expectations and hence quality.

Scholars and other arts writers romantically obsessed with the latest artists and their productions often enjoy cozy relationships with their subjects, depending on them for information and explanations, a situation that impedes the objectivity that time and distance can bestow. The risk is real that these so-called art historians will become “glorified publicist[s] or ventriloquist[s] for the artist.” Because the living never remain as constant as the dead, specialists in this field might also find themselves sorting out conflicting responses.

This love affair with the contemporary finds expression in other museum activities. One example is The Met, which for their rebranding intentions commissioned a design and marketing firm–whose website’s tag line proclaims “We are creative partners to ambitious leaders who want to design radically better businesses”–to construct for it a new logo (Slide 9, Fig. 13) and graphical identity. The choice of consultant should not surprise anyone who has heard the director of The Met, Thomas Campbell, refer to the museum as a business.

The split between curatorial mission and corporate practices was nowhere more obvious than at a Met staff meeting regularly presided over by Director Campbell during which a representative of the design company presented its ideas to a roomful of curators and other staff in the fall of 2015. A young student intern confided her shock at the way the woman spoke to the assemblage as if to grade-schoolers who needed simplified instructions to grasp her meaning.

Reactions to the new logo have been almost unanimously negative, including among guards who now display it on their jackets. In focusing excessively on marketing and other business-like strategies, a museum like The Met risks losing status and public trust. Several years before he became the former director of The Met, Philippe de Montebello cautioned: “How we market our museums tells much about how we view ourselves, and we should not expect our public to be unaffected by such attitudes.”

In devising strategies to gain new audiences, museums have again looked to business models, shifting from a “selling mode” that uses its wares–art objects–to attract visitors, to a “marketing mode” that researches (e.g., through focus groups) the needs, interests and character of prospective guests to more effectively lure then in. Museum organizations’ statements reflect this change. No longer placing emphasis on collection-related activities, they demonstrate a new concern with public service and education, even envisioning museums as instruments of “communal empowerment” and “social change.”

This evolution has not stopped there as museums have sought to become everything to everybody. One need only look at the proliferation of concerts, dance performances (Slide 10, Fig. 14) and completely novel events like exercise routines (Slide 10, Fig. 15) that have become staples for many of them. The need of visitors to have a good time, and not that of curators and their collections to inform, has turned the museum experience into one that seeks to provide “…social interaction…spiritual sustenance, emotional connection, intellectual challenge,…[and] consumerist indulgence,” even happiness.

That’s in stark contrast to the original purpose of museums, which was to provide a place for experiencing art. Today the museum not the art has become the destination–as in “let’s go to The Met” as opposed to “let’s go look at some Italian Baroque paintings and sculpture.”

Some of the events offered by these repositories of art have little to do with their contents, although they do have the potential to generate income, like the cash bar on the Great Hall balcony at The Met (Slide, 11, Fig. 16), which on MetFridays becomes a place to meet and hang out with friends (Slide 11, Fig. 17). Much further south, when Tom Walton announced that Crystal Bridges would be converting an old factory into a space for contemporary art, he envisioned “a ‘kind of living room for the community,’ where art, music, performance and food would be on offer in unexpected ways.”

A contemporary museum like the Guggenheim can unapologetically develop events designed to gather “the ‘in-crowd’ of society” under its roof. In the late nineties, the museum’s director of communications and sponsorship could unabashedly admit:

“We are in the entertainment business, and competing against other forms of entertainment out there. We have a Guggenheim brand that has certain equities and properties…[I]f they are here for a party and happen to look at the art and come back again, that’s valuable to us.”

His was the time when many cultural institutions in New York City were beginning to entice new audiences with offerings of up-to-date music and high-styled fashion.

No one summed up this change in targeted audience better than the entrepreneurial former director of the Guggenheim in the 2001 press release on his museum’s partnership with the Venetian Resort Hotel-Casino in Las Vegas and the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia:

“…today the profile of a typical Las Vegas visitor increasingly approximates the profile of the visitors upon which every major museum in the world…depends, and to which they communicate.”

Contending with that kind of attitude, curators find themselves called upon to partner with, rather than guide, audiences through their collections. One trend has museums mounting shows–virtually or on their walls–consisting solely of selections made by “citizen curators,” as if there were no special qualifications for assembling artwork into coherent and informative exhibitions (Slide 12, Fig. 18).

The success of all these schemes has brought crowding and noise to formerly quiet settings conducive to contemplation and extended viewing. At The Met, the Costume Institute has become notorious for taking over galleries already filled with art, effectively shutting down entire viewing areas for months at a time. The 2015 show China:Through the Looking Glass obliterated the Chinese galleries, turning them into rooms reminiscent of discotheques–loud music permeating darkened spaces illuminated with bright spotlighting (Slide 13, Fig. 19).

Curators now must consider crowd flow when they lay out galleries, especially for blockbusters–those temporary exhibitions devised to generate massive numbers. In designing new museum spaces, architects have to choose between cavernous rooms to accommodate the hoards and intimate galleries to provide optimum viewing opportunities for visitors naturally inclined to look at the art.

Museums cannot, however, survive on their gate alone and in addition to relying on the support of individual donors, must also pursue government and corporate funding, contending with a new emphasis on educating children. The study of art for its own sake no longer qualifies a museum’s existence but now must guarantee the acquisition of important academic and/or other life skills.

Providing enlightenment for both adults and young students about the works of art on display (e.g., their origins, materials, subject matter and former contexts) has been giving way to focusing on the viewers’ perceptions, paralleling the shift to indulging entertainment needs rather than offering up works of art as means of engagement.

The matter remains unsettled, however. On one side are those who believe in the value of the old way (providing information), and worry about dumbing down museum education, meeting visitors at their current level of knowledge instead of challenging them with more sophisticated fare. On the opposing side are those who would use art education to teach other skills, including how to look at the art itself–as though a masterpiece could not speak on its own to an untutored audience.

Singlehandedly, modern and contemporary art, now ubiquitous, could easily account for this sea change in approach. One educator with many years experience observing audience response to new art, noted:

“…both modern and contemporary art can produce a great deal of angst, if not negativity…[Visitors] are confused and often hostile when confronted with, for example, an all black canvas.”

Naturally, he had to distract audience attention from the irritant, redirecting their gaze to their own feelings and thoughts. After all, what can be said about an all black, or all white, or all red, canvas that isn’t purely conceptual, having nothing at all to do with the thing before one’s eyes?

In the end, visitors voted with their feet for the art that most appealed to them. In a 2015 compilation of statistics from museums worldwide, art-historical museums monopolized the top five spots (Slide 14, Fig. 20), attesting to the type of museum experience the viewer still prefers. Encyclopedic museums would do well to take stock of the treasures they already possess rather than looking elsewhere for solutions to their financial woes.

Like Glinda told Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, “…you’ve always had the power (Slide 15, Fig. 21).” It’s time for art-historical museums to click those ruby slippers together and return home to what they alone know how to do so well.

[To get a copy of this paper with the endnotes, send your request to deborahfeller@verizon.net]

References

Altshuler, Bruce. “The Met gets a second chance to get contemporary art right.” The Art Newspaper, April 1, 2016, accessed April 3, 2016, http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/the-met-gets-a-second-chance-to-get-contemporary-art-right/.

Bunzl, Matti. In Search of a Lost Avant-Garde: An Anthropologist Investigates the Contemporary Art Museum. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Crow, Kelly, Sara Germano and David Benoit. “New Masters of the Art Universe.” The Wall Street Journal Arts & Entertainment Section, January 23, 2014, accessed April 17, 2016, http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303448204579337154245172202.

Cuno, James, editor. Whose Muse? Art Museums and the Public Trust. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Davidson, Justin. “The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s New Logo Is a Typographic Bus Crash.” Vulture, February 17, 2016, accessed May 5, 2016, http://www.vulture.com/2016/02/metropolitan-museums-new-logo-the-met.html.

Fabrikant, Geraldine. “European Museums Are Shifting to American Way of Giving.” The New York Times Art & Design Section, March 15, 2016, accessed on March 16, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/17/arts/design/ european-museums-are-shifting-to-american-way-of-giving.html

Gamarekian, Barbara. “Corcoran, to Foil Dispute, Drops Mapplethorpe Show.” The New York Times Arts Section, June 14, 1989, accessed on May 1, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/1989/06/14/arts/corcoran-to-foil-dispute-drops-mapplethorpe-show.html.

Goodnough, Abby. “Giuliani Threatens to Evict Museum Over Art Exhibit.” The New York Times Arts Section, September 24, 1999, accessed on May 1, 2016, https://partners.nytimes.com/library/arts/092499brooklyn-museum.html.

Halperin, Julia. “Almost one third of solo shows in US museums go to artists

represented by five galleries.” The Art Newspaper, April 2, 2015, accessed May 5, 2016, http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/ almost-one-third-of-solo-shows-in-us-museums-go-to-artists-represented-by-five-galleries/

____________. “Museums that expand get more visitors, our data analysis shows.” The Art Newspaper, March 31, 2016, accessed April 3, 2016, http://theartnewspaper.com/reports/visitor-figures-2015/if-you-build-it-they-will-come-at-least-for-a-while/.

Kallir, Jane. “Recent Acquisitions (And Some Thoughts on the Current Art Market).” Galerie St. Etienne Newsletter, July 21-October 16, 2015.

Kennedy, Randy. “Crystal Bridges Museum to Open New Space for Contemporary Art.” The New York Times Art & Design Section, March 29, 2016, accessed on March 30, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/30/arts/design/ crystal-bridges-museum-to-open-new-space-for-contemporary-art.html?_r=0.

Kirschbaum, Susan M. “Noticed; Dinner, Dancing and, Oh Yes, Art.” The New York Times Style Section, March 14, 1999, accessed on April 21, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/1999/03/14/style/noticed-dinner-dancing-and-oh-yes-art.html

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “David Copperfield Names as Architect to Redesign Metropolitan Museum’s Modern and Contemporary Art Wing and Adjacent Areas.” Press Release, March 11, 2015, accessed April 10, 2016, http://www.metmuseum.org/press/news/2015/david-chipperfield.

__________________________. “Sree Sreenivasan Named the Metropolitan

Museum’s First Chief Digital Officer.” Press Release, June 20, 2013, accessed April 17, 2016, http://www.metmuseum.org/press/news/2013/sree-sreenivasan.

Meyer, Richard. What was Contemporary Art? Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2013.

de Montebello, Philippe. The Museum: An Imperfect Construct. Course at the Institute of Fine Arts, 2016.

The Morgan Library & Museum. Calendar of Events Winter & Spring, 2016

_________________________. Calendar of Events Spring & Summer, 2016.

Munro, Cait. “What Noteworthy New Artist Records Were Set at New York’s Fall Auctions?” artnet news, November 13, 2015, accessed April 17, 2016, https://news.artnet.com/market/world-auction-records-november-2015-362609.

National Gallery of Art. “Janine Antoni, Sally Mann, Christina Ramberg, and Roger Brown Acquisitions Made Possible by the Collectors Committee Enter the National Gallery of Art’s Collection.” April 22, 2016, accessed May 5, 2016, http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/press/2016/march-cc.html.

Pes, Javier, José da Silva and Emily Sharpe. “Visitor Figures 2015: Jeff Koons is the toast of Paris and Bilbao.” The Art Newspaper, March 31, 2016, accessed April 3, 2016, http://theartnewspaper.com/reports/visitor-figures-2015/ jeff-koons-is-the-toast-of-paris-and-bilbao/.

Pogrebin, Robin. “Art Galleries Face Pressure to Fund Museum Shows.” The New York Times Art & Design Section, March 7, 2016, accessed April 3, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/07/arts/design/art-galleries-face-pressure-to-fund-museum-shows.html?_r=0.

_____________. Robin Pogrebin, “Met Plans a Gut Renovation of Its Modern Wing.” The New York Times Art & Design Section, May 19, 2014, accessed April 10, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/20/arts/design/ in-mets-future-a-redesigned-modern-art-wing.html?_r=0.

_____________. “Metropolitan Museum of Art Plans Job cuts and Restructuring.” The New York Times Art & Design Section, March 7, 2016, accessed April 21, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/22/arts/design/metropolitan-museum-of-art-plans-job-cuts-andrestructuring.html.

_____________. “NOTICED; Dinner, Dancing and, Oh Yes, Art.” The New York Times Style Section, March 14, 1999, accessed April 21, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/1999/03/14/style/noticed-dinner-dancing-and-oh-yes-art.html.

_____________.“2 Art Worlds: Flush MoMA, Struggling Met.” The New York Times Arts Section, April 22, 2016, accessed April 22, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/22/arts/two-art-worlds-rich-modern-and-struggling-met.html.

Rice, Danielle, and Philip Yenawine. “A Conversation on Object-Centered Learning in Art Museums.” Curator 45, no 4 (October 2002).

Rodney, Seph. “The Evolution of the Museum Visit, from Privilege to Personalized Experience.” Hyperallergic: Sensitive to Art & its Discontents, January 22, 2016, accessed January 25, 2016, http://hyperallergic.com/267096/ the-evolution-of-the-museum-visit-from-privilege-to-personalized-experience/.

Schulte, Erin. “Most Creative People: A Q&A With The Met’s Chief Digital Officer, Sree Sreenivasan.” Fast Company, April 7, 2014, accessed April 17, 2016, http://live.fastcompany.com/Event/Most_Creative_People_Sree_Sreenivasan.

Sutton, Benjamin. “Crunching the Numbers Behind the Boom in Private Art Museums.” Hyperallergic: Sensitive to Art & it Discontents, January 21, 2016, accessed January 22, 2016, http://hyperallergic.com/269548/crunching-the-numbers- behind-the-boom-in-private-art-museums/.

Tomkins, Calvin. “The Met and the Now: The museum finally goes modern.” The New Yorker, January 25, 2016, 32-36.

Vogel, Carol. “Relentless Bidding, and Record Prices, for Contemporary Art at Christie’s Auction.” The New York Times Art & Design Section, November 14, 2012, accessed April 17, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/15/arts/design/record-breaking-prices-at-christies-auction.html?_r=0.

Voon, Claire. “Report Advises Museums on How to Be More Inclusive and Maximize Happiness.” Hyperallergic: Sensitive to Art & its Discontents, March 10, 2016, accessed March 3, 2016, http://hyperallergic.com/ 281215/report-advises-museums-on-how-to-be-more-inclusive-and-maximize-happiness/.

Weil, Stephen E. “From Being about Something to Being for Somebody: The Ongoing Transformation of the American Museum” in Making Museums Matter. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2002.

Posted in Art Historical Musings |

Print This Post

Tuesday, May 12th, 2015 Print This Post

Tuesday, May 12th, 2015

Drawn to Perfection:

Annibale Carracci

Works on Paper

[To view the slide show in a separate tab while reading the text, place the mouse pointer over the first slide, right click, select <This Frame>, then <Open Frame in New Tab>.]

[slide 1: Title]

[slide 2: Self-Portrait [Autoritratto col cappello “a quatre’acque”] (April 17, 1593, oil on canvas, 9½ x 7? in [24 x 20 cm]). Galleria Nazionale, Parma, Italy.]

Legend has it that when Annibale Carracci was a young boy returning to Bologna with his father from a trip to Cremona and they were set upon by robbers, the lad’s precocious ability to render in line what presented itself to his eye aided in the apprehension of the criminals. The youthful Annibale sketched the culprits from memory so accurately that they were easily recognized and brought to justice quickly enough to ensure return of his father’s stolen money.1

While that and other stories that grew up around the famed artistic family of Carracci might well be apocryphal, the existence of these tales of artistic prowess do bear witness to the high regard in which the two brothers and their cousin were held, and in particular to Annibale’s prodigious drawing skills. Born in 1560 in Bologna, the youngest of the triumvirate that included Agostino (his older brother by three years) and their older cousin Ludovico (born in 1555), Annibale was characterized by one of his early biographers as a scruffy, introverted, envious and financially naive prankster.2

Never one to be ashamed of his social standing, Annibale often chided the scholarly, upwardly-striving Agostino–who was far more educated than his younger brother–on the way he hobnobbed with courtiers and the like. To put Agostino in his place, one day in Rome where they were working in the Palazzo Farnese, Annibale handed his pompous brother a letter while they were in the midst of a well-bred group that then eagerly awaited the unveiling of its contents. Much to Agostino’s embarrassment, the opened missive contained a drawing of their parents: father in his spectacles threading a needle and mother holding a pair of scissors,3 a not-so-gentle reminder of the brothers’ humble origins.

For Annibale, drawing trumped speech when it came to personal expression, a stance he made quite clear in another face-off with his loquacious brother who was going on at length about the antique marvels he was discovering after his recent move to Rome to help out at the Farnese. When Agostino made the mistake of taking to task the silent Annibale for not joining in the erudite conversation, accusing him of lacking appreciation for the ancient works, Annibale once again got the better of his older brother with charcoal.

Unbeknownst to Agostino until too late, on a nearby wall Annibale had begun a drawing designed to communicate his reverence for the Roman art he was discovering. When done, he stepped aside to display a perfect rendering from memory of the Laocoön. The onlookers praised the younger artist. Agostino fell silent, and Annibale walked away triumphant–but not before laughingly admonishing his brother, “Poets paint with words; painters speak with works.”4

From very early on, reaching for a drawing implement had been Annibale Carracci’s first impulse and it continued to be throughout his life even into his last few years, when the heavy toll that illness took on his expressive abilities left him unable to do much else. From the pleasurable exercise of sketching his surroundings to the serious study of posed studio models, this master draftsman always looked first to his teacher nature for whatever answers he needed, supplementing it with metaphorical (and sometimes actual) forays into the studios of other artists to draw from their work. Not only did Annibale “speak with [his] works,” he also thought with them–evident in the many surviving pages of preliminary ideas for compositions that he hatched and developed, and often later discarded. Ultimately, these various aspects of his drawing practice would coalesce into a full-size cartoon used for transferring his final design onto wall, canvas or copper plate.

[slide 3: A Man Weighing Meat (c. 1582-83, red chalk on beige paper, 1015/16 x 61/16 in [278 x 170 cm]). Collection Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

The Butcher Shop (1583, oil on canvas, 73 x 105 in [185 × 266 cm]). Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford, UK.]

By the time he drew A Man Weighing Meat (c. 1582-83), the twenty-something-year-old Annibale had already been drawing for many years, but now his interest in depicting everyday life found expression in genre paintings of a type unlike the pastoral idylls of his contemporaries.5 Here he has posed his model, probably a workshop apprentice,6 in the garb of a butcher and given him props–a balance (stadera) for weighing meat along with a stand-in for a slab of flesh–that find their way into The Butcher Shop (1583), one of his earliest known paintings.

The bare-elbow study to the right of the figure in the red-chalk drawing reflects a rethinking of the pose that will appear in the final composition; Annibale angled upward the forearm and rolled back the sleeve. Highlighting the artist’s selection of an expedient rather than exact model, the character of the butcher shop worker in the painting differs from the assistant in the studio; he is older with a neatly trimmed beard, taller stature and somewhat slimmer build. His hat, of a different style, sits back on his head rather than forward as in the drawing.

Early on in the absence of significant commissions for the Carracci shop, genre paintings, like small devotional pictures, provided a quick and relatively easy way for the three young men to churn out work that they could sell on the open market and that would also advertise their skills.7 For Annibale, who had been sketching from life for years, it provided a natural extension of his artistic interests, “demand[ing] little more than a direct and forthright approach to the visual material.”8

[slide 4: A Domestic Scene (1582-1584, pen with brown and gray-black ink, brush with gray and brown wash, over black chalk, 12⅞ x 9¼ in [32.8 x 23.6 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.]

In a very different kind of scene as well as medium, Annibale assembled three figures and a cat around a fire. A young woman, holding a cloth or garment, leans over the flame and looks back toward a young girl, vaguely indicated in line and wash, while a much younger child merges visually with his caretaker’s skirt. A close look at the actual drawing revealed a lack of spontaneity in the manner in which the ink wash was applied, especially in the woman’s skirt, where Annibale–instead of drawing the brush down the form and guiding the pool of diluted ink–seems to have attempted to blend it as he would have done with oil paint, resulting in a somewhat overworked appearance and mild abrasion of the paper. It would not be long before he began to produce far more accomplished ink drawings.

[slide 5: The Virgin and Child Resting Outside a City Gate (n.d., pen and brown ink, brush with traces of brown wash, on light brown beige paper; traces of framing outlines in pen and brown ink, 7⅜ x 8½ in [18.8 x 21.6 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.]

A small, undated compositional sketch of The Virgin and Child Resting Outside a City Gate contrasts in ink handling with the earlier genre scene. Here evenly spaced, parallel hatching designates shadow while sure lines pick out the landscape and architectural features. Schematic rays of the sun–which reappear in a very late pen drawing9–disappear behind horizontal bands of clouds, and figures diminishing in size create a feeling of recession into space. A discreetly contoured area of thinned ink on the shaded side of the Virgin’s head has been applied without any fuss, first a middle-value wash and then a much darker band in the deeper shadow on the periphery of the head–no attempt being made to blend the two. The Virgin’s face, redolent with Correggio sweetness,10 also suggests a date later than the domestic scene.

Not only did Annibale borrow from the output of other artists, he thought deeply about the differences in their styles, forming definite opinions about their work, a fact that runs contrary to the impression of him given by his early biographers as someone uninterested in the theoretical aspects of art. The postilles (marginal notes) in his copy of Vasari’s Lives demonstrate this awareness. Lauding Andrea del Sarto and Michelangelo, Annibale disparaged the “mannered tradition of Florentine painting,”11 noting too the uselessness of comparing Michelangelo with Titian. “Titian’s things are not like Michelangelo’s; they may not be totally successful but they are more lifelike than Michelangelo’s; Titian was more of a ‘painter’…and if Raphael was superior in some parts to Titian, Titian nonetheless surpassed Raphael in many things.”12

Apparently no less contemplative than his scholarly brother or intellectual cousin, Annibale joined them both in their first major commission–two rooms in the Palazzo Fava in Bologna, secured through family connections and their willingness to work at a discounted rate, beginning the project about 1583. The smaller room, which was to contain a frieze about the myth of Europa, was assigned to Annibale and Agostino, while Ludovico, the older and at that time accepted head of their workshop, tackled the larger one, which would tell the story of Jason and the golden fleece. Before all the frescoes were completed, the brothers would join their cousin in the more important space.13

[slide 6: The Meeting of Jason and King Aeëtes (c. 1584, fresco). Palazzo Fava, Bologna, Italy.

The Meeting of Jason and King Aeëtes (c. 1584, pen and black ink with gray-brown wash over black chalk, squared twice in black and red chalk, 10 x 12⅜ in [25.4 x 31.5 cm]). Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich, Germany.]

Annibale’s small ink drawing squared twice for transfer that illustrates The Meeting of Jason and King Aeëtes (c. 1584) shows the composition in a well advanced state as probably presented to the patron, Count Filippo Fava. On the verso containing one of the earliest studies, Annibale had inked figures in their respective perspectival planes, including the accompanying termine,14 those illusionistically painted statues that framed the fresco panels.

[slide 7: The Meeting of Jason and King Aeëtes (c. 1584, pen and black ink with gray-brown wash over black chalk, squared twice in black and red chalk, 10 x 12⅜ in [25.4 x 31.5 cm]). Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich, Germany.

Orpheus Holding a Lyre (before 1584, oiled black chalk over black chalk, heightened with white chalk, on gray-blue laid paper, mounted on wove paper, 16⅓ x 9⅓ in [41.5 x 23.8 cm]). National Gallery of Art, Ontario, Canada.]

Following such compositional imaginings and before the construction of the modello for his client, the artist would research individual poses,15 using not just models from the studio but also from his recollections of previously observed persons and/or sculpture. Annibale’s Orpheus Holding a Lyre (before 1584) shows how well stocked his pictorial memory bank already was. Too general to have been a life study, it might also have been based on one already executed, or refer to some other two-dimensional image.

Lauded for his visual memory, Annibale was reported to have told a friend that “he never–except once, with certain bas-reliefs–had to record for purposes of future recall anything he had looked at carefully.”16 As a group, the Carracci made a regular practice of honing their ability to mentally retain what they had observed. Upon returning home from life drawing sessions and before doing anything else, they would each pick up a scrap of paper and endeavor to commit to it what they had just recently seen, enlivening it with more animation than the original pose.17

[slide 8: Polyphemus (early 1590s, black chalk with traces of white heightening on blue-gray paper, laid down, 1611/16 x13⅞ in [42.4 x 35.2 cm]). Galleria degli Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Florence, Italy.]

Another good example of Annibale’s drawing from his internal image bank, the black-chalk drawing of Polyphemus for a later cycle of frescoes at the Palazzo Fava sets an almost caricatured head on a rippling mass of torqued muscle and bone, about to catapult the small boulder gripped by the one-eyed giant. Pentimenti in the hand suggest final figural considerations in an image already close to the painted one, including reflections on the play of light and shadow to be used in the fresco.

[slide 9: Sheet of Caricatures (c. 1595, ink on paper, 7⅞ x 5⅛ [20.1 x 13.9 cm]). British Museum, London.]

Drawn to facial features, Annibale joined his cohorts in exaggerating them in a form of art that derives its name from theirs: caricature. Playful by nature, known for their love of practical jokes,18 always looking to exploit drawing’s potential to distill essence from reality, the artists had fun deliberately distorting the appearance of certain individuals. In a sheet of these faces, Annibale has sketched in the upper left an ordinary looking profile of a man and in the lower right has riffed on this, opening the eyes wider and hooking the nose more. The receding mouth of the man is exaggerated in several of the profiles on the sheet. Such exercises are to be distinguished from the creation of grotesques–products of the imagination.19

Quite opposite in emotional tone, Annibale’s portrait drawings have a quiet intensity, especially those of children, the models for which he drew from youngsters around the studio–“assistants and friends or relatives who frequented the Carracci shop and academy.”20 As with his other subjects, these young people furnished handy objects to study, though Annibale seems to have had a special affinity for the “serious and meditative”21 interiority that children often manifest in their quiet moments.

[slide 10: Profile Portrait of a Boy (1584-1585), red chalk on ivory paper, 813/16 x 6⅜ in [22.4 x 16.2]). Galleria degli Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Florence, Italy.]

In the early red-chalk drawing Profile Portrait of a Boy (1584-1585), the artist has posed the lad in strict profile and taken considerable care to sculpt his form with light and shadow, gently blending strokes on the smooth-skinned cheek and distinctly denoting the direction of hair strands. Annibale deftly reserved the ivory of the page for the glittering highlights of the hair and the prominent helix of the ear.

[slide 11: Head of a Boy (c. 1585-1590, black chalk on reddish brown paper, laid down, 227/16 x 915/16 in [316 x 252 cm] including a 2 cm horizontal strip added at the top). Musée du Louvre, Départment des Arts Graphiques, Paris, France.]

A similarly finished portrayal, the black-chalk Head of a Boy (c. 1585-1590) captures the tension of the neck muscle as the child strains to look with wide-eyed concern at something on his right. The down-turned corners of the mouth impart a melancholy mood, suggesting that whatever is outside the viewer’s field of vision might not be welcome. As with the earlier portrait, here too Annibale is far less interested in the clothing than in the boy’s head.

[slide 12: Head of a Smiling Young Man (c. 1590-92, black chalk on gray-blue paper with added strips at top and bottom, laid down, 153/16 x 97/16 in [358 x 240 cm]). Musée du Louvre, Départment des Arts Graphiques, Paris, France.

Madonna and Child in Glory with Six Saints (c. 1591-92, San Ludovico Altarpiece). Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna, Italy.]

Identified as a preparatory sketch for a subsequent altarpiece,22 Head of a Smiling Young Man (c. 1590-92) has been so named because of its perceived happy expression. Yet the face of Saint John the Baptist in the San Ludovico altarpiece, for which it is a study, tells a more complex story of the triumphant validation of miracle that the apparition of the Madonna and child provides, a look for which Annibale was searching in this particular drawing, one unlikely to have been taken from life.

[slide 13: The Lutenist Mascheroni (c. 1593-1594, red chalk heightened with white chalk on reddish brown paper, the lower left corner slightly cut, 163/16 x 113/16 in [411 x 284 cm]). Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, Austria.

The Lutenist Mascheroni (c. 1593-1594, pen and brown ink on cream paper, laid down, the lower left corner cut and made up, 77/16 x 415/16 [188 x 126]). Collection Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

Portrait of the Lutenist Mascheroni (c. 1593-1594, oil on canvas, [305/16 x 253/16 in 77 x 64 cm]). Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden, Germany.]

For The Lutenist Mascheroni (c. 1593-1594), another preparatory drawing, Annibale picked up his red chalk again and using much the same approach as he did for the earlier Profile Portrait of a Boy, brought the picture to a high level of finish, perhaps to serve as an immediate model for the painting.23 That the eyes are similarly out of convergence in all three versions implies that Annibale deliberately arranged Mascheroni’s facial features to block eye contact with the viewer. Posed stiffly, the disengaged lutenist reveals little about himself–a common feature of this artist’s portraits24–but a lot about Annibale’s own interpersonal style and his tendency to treat people as objects rather than subjects.

The studies of male nudes for the herms and ignudi that adorn the haunches of the Palazzo Farnese’s barrel vault, however, seem far more animated, exuding sensual energy. When the newly appointed nineteen-year-old Cardinal Odoardo Farnese decided to decorate various rooms in his palazzo in Rome, he would have none other than the Carracci.25 Annibale as the first to become available, arrived in the antique city to begin work in November 1595,26 the beneficiary of what seemed like an unparalleled opportunity but one that ultimately led to disappointment, despair and death.

[slide 14: Project for the Decoration of the Farnese Gallery (1597-98, red chalk with pen and brown ink on cream paper, 15 ¼ x 10⅜ in [38.8 x 26.4 cm]). Musée du Louvre, Départment des Arts Graphiques, Paris, France.]

After first completing the Camerino (the Cardinal’s study), Annibale was joined in 1597 by his brother Agostino to assist him with the much larger project of the ceiling of the Farnese gallery.27 After playing with various concepts in a series of ink drawings, Annibale settled on an illusionistic array of framed paintings covering two-dimensional architectural elements supported by herms, and a frieze of scenes framed by ignudi, eschewing a single point of view for the entire project.

[slide 15: Palazzo Farnese Ceiling (fresco, 1597/98-1601). Rome, Italy.]

When Agostino “pressed for a unified illusion based on one-point perspective,” Annibale mocked his brother’s idea by suggesting they install a sumptuous chair at the only spot in the huge room from which the paintings would be viewable in a way that made spatial sense to the onlooker.28 The result of the lead artist’s decision was a design that could be read from any place in the room, but one that would always include some upside-down images.

[slide 16: Atlas Herm with Arms Raised (1598-99, black chalk heightened with white on gray-blue paper, 189/16 x 14¼ in [47.2 x 36.3 cm]). Biblioteca Reale, Turin, Italy.]

Atlas Herm (1598-99, red chalk on cream paper, laid down, 13⅝ x 713/16 in [34.5 x 19.8 cm]). Musée du Louvre, Départment des Arts Graphiques, Paris, France.]

To create the three-dimensional architectural illusion of his intentions, Annibale had to turn flesh into stone.29 Atlas Herm with Arms Raised (1598-99), the end drawing result of one such attempt, shows how he enhanced an original male nude study by pumping up the muscles and juxtaposing bright highlights with lower-value black chalk to impart a marmoreal quality to the form. Highly unusual for Annibale is the come-hither direct eye contact the herm makes with the beholder–originally the artist. The turned-away head in the lower left might represent some second thoughts but in the fresco Annibale kept to his original idea.

In returning to red-chalk in a different Atlas Herm (1598-99), at a time when he favored black and white chalk on blue paper,30 Annibale might have wanted to take advantage of the medium’s potential for rendering the warmth of flesh. In comparison with the Atlas Herm with Arms Raised, this herm would then represent an earlier stage in the transformation of the living model into a marble sculpture.

[slide 17: A Seated Ignudi with a Garland (1598-99, black chalk heightened with white chalk on gray paper, 16¼ x 16⅛ in [41.2 x 41 cm]). Musée du Louvre, Départment des Arts Graphiques, Paris, France.

Detail of Ignudi and Herms, Palazzo Farnese Ceiling (fresco, 1597/98-1601). Rome, Italy.]

Inspired by Michelangelo’s male ignudi on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican,31 Annibale populated his Farnese vault with analogous figures. Lightly sketched construction lines and first-thought contours in A Seated Ignudi with a Garland (1598-99) provide a window into the artist’s drawing process. Among other changes, he reduced the size of the proper right lower leg, further accentuating the tapering of the massive torso toward the pelvis and legs. In making that choice, Annibale further demonstrated his preference for design over accurate perspective.

[slide 18: Study of a Recumbent Nude, Lying on his Side (n.d, black chalk with white and pink heightening, on gray-blue paper, 14½ x 19⅔ in [36.8 x 49.9 cm]. Royal Library, Windsor, England.

Study of a Recumbent Nude, Viewed from the Head (n.d., black chalk with white heightening on gray-blue paper, 8½ x 15½ [21.5 x 39.5 cm]). Musée du Louvre, Cabinet des Dessins, Paris, France.]

Very different in overall appearance are two black-chalk life studies executed during Annibale’s Roman sojourn,32 each a Study of a Recumbent Nude, one Lying on his Side and the other Viewed from the Head. In the former, the artist has faithfully observed the unadorned truth of the effect of gravity on muscle and skin, particularly noticeable where the bones jut out along the uppermost contour of the rib cage, pelvis and greater trochanter. Unlike in Annibale’s imaginative male nudes, here only the left biceps is rounded, accurate for a flexed position, the right one being flat as appropriate for extension.

Annibale was less satisfied with reality in Study of a Recumbent Nude, Viewed from the Head, thickening the left thigh considerably and, less so, the right arm. This drawing might have started out as a life study and accrued revisions along the way, including a slight change in pose for better effect. Both drawings bear witness to the artist’s intense absorption in the task at hand.

Content in the practice of his art, Annibale never adjusted to the rarified atmosphere and courtly trappings of the Palazzo Farnese, preferring instead the solitude of his room and the company of his students. Minimally attentive to his physical presentation and melancholic in disposition, he actively avoided any unnecessary association with nobility. On an evening stroll when caught carrying a knife, Annibale’s chosen silence about his service to the Cardinal led to time in jail. Likewise, at another time on learning of an impending personal visit from the Pope’s nephew, he escaped through a side door.33

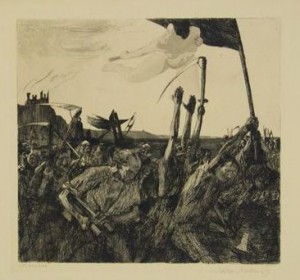

[slide 19: An Execution (1600-03, pen and brown ink on dark cream paper, laid down, 7½ x 119/16 in [19 x 29.3 cm]). Collection Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.]

In Rome, Annibale’s idiosyncrasies stood out far more than they did in Bologna,34 causing no small distress to an already sensitive soul. No wonder, then, that he would be drawn to the ritual of a public hanging, capturing the salient details with brown ink in An Execution (1600-03). In the pictured narrative, as an audience peers over the back wall, exercising its communal responsibility in a purification rite designed to ensure the conversion and repentance of the condemned, a friar holds up a devotional image for the criminal to ponder as he is dragged up the ladder to the gallows,35 his fate foretold by the hanging corpse nearby. Another instrument of death awaits employment on a table to the right.

For Annibale, life soon imitated the morbidity of a hanging when the payment he received for eight years of loyalty to the Farnese projects failed to meet his expectations and in fact, proved to be more of an insult than a reward. The five hundred gold scudi brought on a saucer to the artist’s quarters, perhaps the result of the machinations of a sycophant at court, plunged Annibale into a depression from which he never recovered.36

In the summer of 1605, before tackling the Cardinal’s next project–the decoration of the great hall of the Palazzo Farnese–Annibale fled permanently from the court bustle, seeking seclusion in lodging behind the vineyards of the Farnesina across the Tiber. Later he took up residence on the Quirinal Hill, where the open air and pleasant view could have been more conducive to recovery.37 By 1606 he was in yet another area of Rome some distance from the Palazzo.38

The nature of his illness was such that Annibale experienced intermittent periods of productivity during which he produced a few paintings, supervised and assisted with projects by his students–especially his favorite, Domenichino39 –and continued to draw. He even began to experiment with a new technique, using a thick-nibbed pen (perhaps made of reed) and skipping any ink wash.40

[slide 20: Danaë (1604-05, pen and brown ink on cream aper, laid down, upper right corner cut, 7⅝ x 10⅛ in [19.4 x 25.7 cm]). Collection Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

Titian, Danaë (1545, oil on canvas, 47.2 × 67.7 in [120 × 172 cm]). Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy.]

After a hiatus of four years during which he had resigned from painting, Annibale resumed activity for a few years beginning in 1604,41 accepting a commission from Camillo Pamphilj to paint a Danaë. Perhaps challenged by the presence of Titian’s painting of the same subject in the Palazzo Farnese,42 the artist borrowed the general idea from the Venetian painter of a reclining female nude, on a bed, in a landscape setting, along with the voluptuous form of her body, changing the pose of the princess and the position of Cupid to make the composition his own. Manipulating the thick-nibbed pen to produce both fat and thin lines, Annibale has his Danaë (1604-5) eagerly reaching for the gold coins as they descend from above and come to rest on her left inner thigh.

[slide 21: Self-Portrait on an Easel and Other Studies (c. 1604, pen and ocher-brown ink on cream paper, 9¾ x 7⅛ in [24.8 x 18.1 cm]). Collection Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

Daniele da Volterra (Daniele Ricciarelli), Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) (c. 1544, oil on wood, 34¾ x 25¼ in [88.3 x 64.1 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.]

Self-Portrait on an Easel (c. 1604, oil on canvas). The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.]

The period of relative inactivity was bracketed by two self-portrait drawings, the later one a meditation on portraiture in general and perhaps more specifically, on the artist’s own legacy. In a picture related to the painting Self-Portrait on an Easel (1604), Annibale has positioned a bearded, older man resembling Michelangelo to the right of his arrangement of images that strike poses similar to that of a portrait of this revered forebear (Ricciarelli’s oil on wood) that resided at the Palazzo Farnese from 1600 onward.43 In addition, a similar profile portrait of a seventy-one-year-old Michelangelo introduced a biography of him that had been circulating in Rome since 1553.44

Multiplying his own image, Annibale suggested mirrors, windows, picture frames and the interior of a studio inhabited by a painted canvas on an easel, accompanied by a small menagerie of household pets. Again, inked lines vary in thickness, and darks are indicated by overlapping and hatched lines. The self-portrait in the finished painting is all eyes, wide open, looking out at the viewer, while the mouth disappears into a blur of shadow, an apt representation of an artist not known for eloquence.

[slide 23: Self-Portrait (c. 1600, pen and brown ink on buff paper, laid down on another sheet on which is drawn a decorative border in pen and black ink with gray wash over graphite, 5¼ x 4 [13.3 x 10.2 cm]). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California.]

Although done about 1600, the earlier of the two self-portrait drawings from this period resonates well with Annibale’s last days. Depicting himself leaning on the picture frame, the artist rendered his visage in fading brown ink, cast a shadow over eyes with lowered lids of sadness, turned down the corners of his mouth in a frown, and darkly superimposed over the top of the cartouche a suggestion of a skull.45

Both self-portraits portend death, undoubtedly reflecting Annibale’s deteriorating physical and mental condition. On July 16, 1609, he “died miserably.”46 Since then writers have made much of Annibale’s melancholic disposition47 and its link to his ultimate demise.48 Most likely he died from tertiary syphilis. In his biography of the artist, Bellori asserted that his “death…was hastened by amorous maladies of which he had not told his doctors”49 and in fact, the artist’s symptoms as described by Mancini50 and Agucchi51 conform to those of end-stage syphilis.52

Though the world lost a master draftsman when Annibale Carracci died prematurely at the age of forty-nine, it gained a treasure trove of drawings, cherished enough to survive the centuries. Among those who looked to the Bolognese artist for inspiration was a certain Dutch painter living in Amsterdam in the seventeenth century. The owner of a drawing of people swimming in a landscape penned by Annibale was none other than Rembrandt himself. Unfortunately, the exact identity of the scene has yet to be determined.53

__________________________________

1 Giovanni Pietro Bellori, The Lives of Annibale & Agostino Carracci, trans. Catherine Enggass (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1968), 7.

2 Carlo Cesare Malvasia, Malvasia’s Life of the Carracci, Commentary and Translation, translated and annotated by Anne Summerscale (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press), 250–51, 254.

3 Ibid., 251.

4 Bellori, 16.

5 Donald Posner, Annibale Carracci: A Study in the Reform of Italian Painting Around 1590, Vol I (New York: Phaidon Publishers, 1971), 9.

6 Daniele Benati, et al, The Drawings of Annibale Carracci (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1999), 49.

7 Posner, 23.

8 Ibid., 24.

9 See Landscape with the Setting Sun (1605-09) in Benati, et al, 289.

10 The Metropolitan Museum of Art online object label. Accessed April 9, 2015: http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/ search/338420?rpp=30&pg=1&ao=on&ft=annibale+carracci+drawings&pos=7&imgno=0&tabname=label.

11 John Gash, “Hannibal Carrats: The Fair Fraud Revealed,” Art History 13:2 (June 1990), 245.

12 Ibid.

13 Posner, 53-54.

14 Benati, et al, 58.

15 Benati, et al, 44-45.

16 Malvasia devoted many pages to describing Carracci pranks. See 274-289.

17 Malvasia, 290.

18 Ibid., 267.