A Case Study of

Psychoanalysis as an

Art Historical Method

Turn-of-the-nineteenth century Vienna was a fertile time for scientists, intellectuals and artists as the planets aligned to create what has been called “The Age of Insight.” The mind became an object of intense scrutiny for practitioners of medicine, psychiatry, psychology, and the literary and visual arts. New methods that were developed in pursuit of understanding human nature from a biological perspective found usefulness in the study of art and artists.

One resident of the city, Sigmund Freud, created a system of indirect investigation into the psyche using personal experiences like dreams, fantasies, slips of the tongue, and artistic productions. Calling his method psychoanalysis and taking it beyond the confines of his medical practice, Freud applied it everywhere without reservation, writing about jokes and everyday missteps, romance and war, and creativity and art.

Ever curious about Italy and its artists, Freud wrote a book-length analysis of Leonardo da Vinci based on a memory the artist had included in his Codus Atlanticus. In Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood, the doctor uses psychoanalysis with great conviction to answer intriguing questions about this Renaissance master and scientist.

The first German edition of the book, published in 1910, was followed by four more (1919, 1923, 1925 and 1943). An English translation titled simply Leonardo da Vinci appeared in 1916, followed by an additional two (1922 and 1932) before the one under consideration here. In 1964 Alan Tyson, working under the general editorship of James Strachey with Anna Freud and Alix Strachey for The Standard Edition, translated the text with an expanded title for this first American edition.

In his book-length essay, Freud takes as his starting point Leonardo’s description of an event from his childhood, using a flawed German translation of the original Italian, to understand why Leonardo traded art for other inventions and took off in pursuit of scientific knowledge. In typical Freud writing style, the psychoanalyst anticipates all manner of resistance throughout the piece, beginning by assuring those who would question his motives that his intentions are not “‘[t]o blacken the radiant and drag the sublime into the dust’” but rather to further understand a man that he referred to as “among the greatest of the human race.”

Before he tackles the childhood memory, Freud describes Leonardo’s struggles with his art, beginning with the perfectionism that made each painting a major endeavor of upwards of several years and left more than a few unfinished. He cites Vasari and later art historians who quote Leonardo’s contemporaries on the subject, and mentions several specific paintings as examples, including the Last Supper, where the artist’s frustration with the rapid execution required of fresco painting resulted in the technical disaster that has challenged conservationists ever since.

From there Freud begins an elaboration of Leonardo’s personality based on observations by those who knew him in some way, maneuvering closer to his primary thesis by proposing that the artist “represented the cool repudiation of sexuality.” He finds evidence for this in Leonardo’s own words as quoted by Edmondo Solmi, an Italian philosopher of Freud’s time. Soon enough the psychiatrist addresses Leonardo’s homosexuality, declaring that even though the fledgling artist had gotten into trouble with the law for it when he was in Verrocchio’s studio and surrounded himself with beautiful young boys once he was a master, for sure he never actually engaged in sexual activity.

In another secondary source, Freud finds Leonardo averring that “[o]ne has no right to love or hate anything if one has not acquired a thorough knowledge of its nature.” Applying that to the artist’s assumed abstinence, he notes that in this case “[t]he postponement of loving until full knowledge is acquired ends in a substitution of the latter for the former.” Thus, for Leonardo, investigating took the place of creating art and of producing much of anything else.

In his element now, Freud asserts that around age three most children go through a period of “infantile sexual researches” usually precipitated by the advent of a new sibling, which invites the question: whence babies? When repression puts an end to this phase, various outcomes are possible. Freud believed that Leonardo’s unconscious resolution was perfect; by channeling his sexual drive into non-practicing homosexuality and allowing his investigative instinct to reign supreme, the artist-scientist avoided a neurotic resolution, freeing his libido to “act in the service of [his] intellectual interests.”

After establishing this psychoanalytic foundation, Freud provides information about Leonardo’s childhood, noting that the artist was illegitimate, initially lived with his mother, and when five years old went to live with his father, who had recently married. That these inadequate bits of biographical data are poor substitutes for having the analysand before him doesn’t seem to deter the doctor from basing his conclusions on them.

Finally Freud presents the memory, translated for this book from the German text he quotes, Marie Herzfeld’s translation of the Italian original as it appeared in Nino Smiraglia-Scognamiglio’s edition of the Codex Atlanticus. Her version erroneously rendered nibio as vulture when in fact it means kite, a much smaller, non-carrion-eating raptor with the ability to hover in the air due to its long, forked tail. She also omitted dentro (within), which alters the action of the all-important tail. These changes have been indicated in brackets in the rendering of Leonardo’s words that follows.

It seems that I was always destined to be so deeply concerned with vultures [kites]; for I recall as one of my very earliest memories that while I was in my cradle a vulture [kite] came down to me, and opened my mouth with its tail, and struck me many times with its tail against [within] my lips.

After extolling the virtues of psychoanalysis as a tool for deciphering this passage, Freud points to the obvious erotic content, noting that “tail” (coda in Italian) is a common slang term for penis. He then goes on to construct an interpretation of the memory that defies Occam’s razor.

Although he acknowledges the similarity between Leonardo’s memory and the dreams and fantasies of women and passive homosexuals, Freud opts to see it as a symbolic representation of the baby suckling at its mother’s breast. He supports this hypothesis by pointing out that in Egyptian mythology a mother goddess, whose name was Mut (similar to the German mutter for mother), was pictured with a vulture’s head, adding that at the time all vultures were believed to be female.

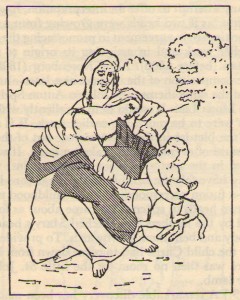

Freud concludes that the memory represents the overdependence on, and eroticization of, Leonardo by his mother, who used him when he was quite young as a substitute for his missing father. In the rest of the essay, Freud looks first for confirmation of his ideas to Leonardo’s art–in the special smiles that grace the faces of his women and in The Virgin and Child with St. Anne, with its hidden vulture.

As further support, the psychoanalyst pulls in his theories on infantile sexuality, the phallic mother, homosexuality and the Oedipal complex. He finds indirect evidence in Leonardo’s writings for a negative relationship with his father, linking it to the artist’s homosexuality and his rejection of religion. Freud even finds meaning in Leonardo’s obsession with flying machines, citing the connection between dreams of flying and sexual performance.

In the final chapter of the book, feigning humility, Freud addresses possible objections to his “pathographical review of a great man,” admitting the limitations of applying psychoanalysis to the biography of someone about whose early life so little is known. He nonetheless confidently asserts that he has accomplished what he set out to do, showing how the circumstances of Leonardo’s childhood, combined with his inherent capacity to repress and sublimate his primitive instincts, resulted in a celibate artist-scientist forever torn between his art and science. Although Freud was well satisfied with his conclusions, their unfavorable reception seems to have discouraged him from tackling other art historical subjects.

Freud came to this particular project via a long-standing interest in Leonardo–once remarking in a letter to his friend Wilhelm Fliess on the artist’s celibacy and left-handedness–and had read Dmitry Sergeyevich Merezhkovsky’s historical novel, Leonardo da Vinci, which he cites in the text as though it were a historical document. His other bibliographical resources include volumes written on Leonardo by an assortment of scholars as well as a long list of his own publications.

Not unlike Leonardo, Freud was enticed away from his original career path by his curiosity. Born in Moravia in 1856 but resident in Vienna from age three until he fled Austria for London in 1938, Freud studied biology and medicine, qualifying as a doctor in 1882. Three years later, a trip to the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris and time spent with the celebrated expert on hysteria, Jean-Martin Charcot, changed his professional direction from clinical neurology to medical psychology. With his Interpretation of Dreams, published in 1900, Freud moved even further away from the laboratory, confining his research to observations of his psychiatric patients and reflections on his own experiences and psyche. Out of that work, he developed the practice of psychoanalysis and his theories about the unconscious.

When he decided to pursue an analysis of Leonardo da Vinci, Freud turned to writings by prominent art historians, among them the German Jean Paul Richter (1847-1937) and the Frenchman Eugène Müntz (1845-1902), whose methods happened to be at odds with each other. Richter, a disciple of Giovanni Morelli (who believed art was best studied by looking at objects with a well-practiced scientific eye), published in 1883 The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci, a two-volume work, first in Italian, then German and English, the last of which Freud consulted. Müntz, on the other hand, believed in the importance of archival research and, opposing Morelli’s focus on connoisseurship, based his studies on documents he unearthed in Italian archives. His monograph Léonard de Vinci, released in 1899, was one of Freud’s references.

If the psychoanalyst was aware of the caldron of ideas that simmered close by, especially in the Vienna School but also elsewhere, about how best the discipline of art history should be practiced, his bibliography doesn’t reflect it. The ideological stew included empiricists who looked to science as a model for the investigation of artworks as physical entities in documented contexts, philosophers who approached the study of art from a metaphysical perspective–more concerned with ideas than things, and a new breed of cultural historians, who occupied a middle ground between the two, finding value in each and adding ethnography and psychology to the mix.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin and Child with St. Anne (c. 1508, oil on wood, 66″ x 44″ [168 x 112 cm]). Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Sketch of The Virgin and Child with St. Anne from Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of his Childhood, page 66.

Freud seems to have gravitated toward outliers like Walter Pater (1839-1894), a British aesthete whose Studies in the History of the Renaissance, a collection of essays published in 1873, had to be recalled because of their anti-religious nature. In his discussion of specific artwork by Leonardo, the analyst relied on those essays plus the work of two others: Oskar Pfister (1873-1956), a Swedish minister with an interest in philosophy and psychology with whom Freud maintained regular correspondence for many years, and whose discovery of a vulture in The Virgin and Child with St. Anne provided critical evidence for the hypothesis expounded in the book; and German-born Richard Muther (1860-1909), an emotionally expressive writer whose description of images tended toward the “lurid and erotic.” In fact, Freud’s insufficient knowledge of art history and the scholarship on Leonardo made mistakes inevitable and stood in the way of producing “a meaningful art historical essay on the artist.”

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa (1503-17, oil on poplar, 30″ x 21″ [77 x 53 cm]). Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Because his interest was primarily psychological, Freud could be expected to seek out those who approached the study of art from a similar perspective. While there is surely much to be gained through the understanding of artists’ intrapsychic development and interpersonal relationships, Freud’s system of thought–psychoanalysis–contains many flaws, not the least of which is his attribution of adult sexual feelings to infants and children.

In explaining Leonardo’s memory, the doctor first must explain how the vulture’s tail comes to be symbolic of the artist’s intense erotic attachment to his mother and how that desire later morphs into homosexuality. He does this by invoking the phallic mother who is imagined to possess a penis by the little boy appalled at the thought that someone he loves so dearly should lack such a precious appendage. This intense mother-son bond is reinforced by Leonardo’s oversolicitous mother and absent father, and the child’s unconscious identification with the idolized mother. The boy grows up to be a man who love boys in the same way his mother loved him. Here Freud confuses homosexuals with pedophiles; the former are attracted to other men while the latter prey on vulnerable children.

Because Freud’s reasoning about such Leonardo mysteries as his perfectionism, depiction of smiling women, and turn from art to scientific research depends so heavily on the Oedipus complex and other aspects of his theory of infantile sexuality, it’s important to know how he came to substitute those assumptions for his empirically based seduction theory of hysteria.

In his work with women suffering from what would now be called Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder but was then diagnosed as hysteria, Freud came to the unavoidable conclusion that their symptoms stemmed from “one or more occurrences of premature sexual experiences…[in] the earliest years of childhood,” incidents forced upon them by adults in their immediate family environment. Since most of his patients were women whose fathers came from prominent Viennese families, his observations were met with a chill that forced him to retract his basic premise and instead attribute his patients’ symptoms not to memories but to fantasies growing out of infantile sexual desires for their fathers. The construction of the Oedipus complex followed. Boys, Freud asserted, coveted their mothers, wished to do away with the competition, and feared castration at the hands of vengeful fathers.

Had Freud held to his original discovery, perhaps he would have understood Leonardo’s memory of a visit from a bird that places its long tail in his mouth as a screen memory for oral rape. On that stronger foundation, the doctor could have constructed a different theory about Leonardo’s homosexual activity in Verrocchio’s workshop and his later predilection for boys.

In The Aetiology of Hysteria, Freud observed a link between adult hysterical symptoms and adolescent trauma, which he then traced to childhood sexual assaults. Rather than seeing Leonardo’s interest in younger males as a manifestation of his over-identification with his mother, the analyst might have chosen the simpler conclusion, that to avoid intolerable feelings of victimization, the artist unconsciously took the role of perpetrator and re-enacted his abuse with others, a common outcome of early sexual trauma. With that far less complex connection, Freud might then have been able to link Leonardo’s perfectionism with his need to compensate for the shame he carried as a result of being sexually abused.

In addition to those missed opportunities, Freud was led on a wild vulture chase by a significant error in translation. His excursion into Egyptian hieroglyphics and mythology in support of his contention that Leonardo’s memory of the bird and the appearance of its image in The Virgin and Child with St. Anne (as illustrated by his good friend Pfister) proved the artist’s erotic attachment to his mother, while fascinating, must be disregarded.

It would be unfortunate if at this point one concluded that psychoanalysis has little if anything to contribute to the study of art and the artists who create it, for when Freud briefly left behind his obsession with Leonardo’s “vulture-fantasy” and sexualized relationship with his mother and looked instead at his paintings, he had much to offer. In associating the enigmatic smile of the Mona Lisa with Leonardo’s memory of his mother’s adoring gaze, and the mother-and-daughter dyad of The Virgin and Child with St. Anne with the five-year-old boy’s relationship with his adopted mother and paternal grandmother, both of whom lived in his father’s house and took over his care from his single mother, Freud kept it simple and raised intriguing questions. In expounding on those connections, he assumed kindness and tenderness on the part of the pictured women, but one could just as easily see in these images an unconscious wish for an ideal that never was.

In either case, in directly encountering Leonardo’s art, drawing upon limited but salient biographical data and applying the principals of psychoanalysis, Freud introduced to the study of art a potentially powerful tool. Had he not abandoned his initial discoveries about childhood trauma and spent his genius on devising convoluted theories to explain hysterical symptoms, he might have come to more convincing conclusions about the life of Leonardo da Vinci and made an important contribution to the field of art history.

Bibliography

– Fermi, Eric. Art History and its Methods. New York: Phaidon Press, 2011.

– Freud, Sigmund. Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood. Translated by Alan Tyson. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1964.

– _____________. On Creativity and the Unconscious: Papers on Art, Literature, Love, Religion. Edited by Benjamin Nelson. New York: Harper & Row, 1958.

– _____________. “The Aetiology of Hysteria.” In The Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory, by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson. New York: Penguin Books, 1984.

– Italian-English Dictionary. New York: Barron’s Educational Series, 2007.

– Kandel, Eric R. The Age of Insight: The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain, from Vienna 1900 to the Present. New York: Random House, 2012.

– Kultermann, Udo. The History of Art History. New York: Abaris Books, 1993.

– Onians, John. Neuroarthistory: From Aristotle and Pliny to Baxandall and Zeki. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

– Sorensen, Lee, ed. “Eugéne Müntz” in Dictionary of Art Historians, www.dictionaryofarthistorians.org.

– _______________. “Jean Paul Richter” in Dictionary of Art Historians, www.dictionaryofarthistorians.org.

– _______________. “Walter Pater” in Dictionary of Art Historians, www.dictionaryofarthistorians.org.

– Simmons, Laurence. Freud’s Italian Journey. New York: Rodopi B. V., 2006.

– Wikipedia. “Oskar Pfister.” Last modified September 21, 2013. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oskar_Pfister.

[A version of this review with footnotes is available. If interested, contact deborahfeller@verizon.net.]