Art Reviews

Print This Post

Sunday, November 24th, 2013 Print This Post

Sunday, November 24th, 2013

Doing Together

What Can’t Be Done Alone:

An Integrative Approach to

Raped by Käthe Kollwitz

***********************************************

The Blind Men and the Elephant

by John Godfrey Saxe (1816-1887)

It was six men of Indostan,

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind.

The First approach’d the Elephant,

And happening to fall

Against his broad and sturdy side,

At once began to bawl:

“God bless me! but the Elephant

Is very like a wall!”

The Second, feeling of the tusk,

Cried, -“Ho! what have we here

So very round and smooth and sharp?

To me ’tis mighty clear,

This wonder of an Elephant

Is very like a spear!”

The Third approach’d the animal,

And happening to take

The squirming trunk within his hands,

Thus boldly up and spake:

“I see,” -quoth he- “the Elephant

Is very like a snake!

“The Fourth reached out an eager hand,

And felt about the knee:

“What most this wondrous beast is like

Is mighty plain,” -quoth he,-

“‘Tis clear enough the Elephant

Is very like a tree!”

The Fifth, who chanced to touch the ear,

Said- “E’en the blindest man

Can tell what this resembles most;

Deny the fact who can,

This marvel of an Elephant

Is very like a fan!”

The Sixth no sooner had begun

About the beast to grope,

Then, seizing on the swinging tail

That fell within his scope,

“I see,” -quoth he,- “the Elephant

Is very like a rope!”

And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong!

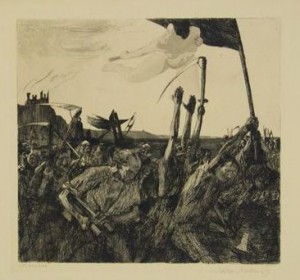

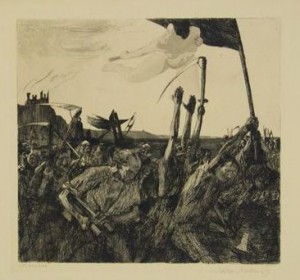

Raped (Vergewaltigt) (1907/08, etching on heavy cream wove paper, 11¾″ x 20⅝″ [29.9 x 52.4 cm)]. Plate 2 from the cycle Peasant War. Proof before the edition of about 300 impressions of 1908. Knesebeck 101/Va. Photo © Kollwitz Estate. The way to the blockbuster show led through a long corridor that at its beginning widened into an area whose walls the museum exploited for temporary exhibitions of works on paper too light-sensitive for permanent display. Attracted by the drawings and prints in this accidental gallery, some visitors slow for a more sustained look.

One image, which looked like an ill-kept garden, revealed itself via the wall text to be a 1907/8 etching called Raped by a German artist named Käthe Kollwitz,1 who lived between 1867 and 1945. Viewers who took the time to look more closely would detect amid the foliage a woman with legs splayed and head thrown back, the subject of the picture’s title. At that point most would move on to look at other works. Some few would linger, wanting to learn more about this depiction of sexual assault.

The only other information available at that moment–the description nearby on the wall–identified the brown-ink print as a plate from the Peasant War series executed on heavy cream wove paper. Although unschooled in art historical methods, an intrigued viewer might intuitively know that much could be gained by exploring every aspect of this simply-framed etching.

Drawing the viewer’s immediate attention and bisecting the bottom of the almost-double-square (approximately 12-by-21-inch) composition, the woman’s foot–set off from lighter surroundings by its dark sole–meets the picture plane and beckons the onlooker to follow its arch to the foreshortened, thick-set leg that disappears under a skirt. The eye continues along an arc, through the torso and extended neck, stopping at the chin beyond which lies the shadowed face with its features distorted by the angle of view.

Searching for the rest of her, the observer discovers behind a bent-over, wilted sunflower the right leg, forming a horizontal line with the top edge of the skirt and ending in a foot that points toward the upper left corner. Assisted by a nearby still-upright flower slanted at an angle running parallel to it, the foot directs the gaze to a blossoming sunflower in the background’s deep shadow, the form of which echoes the head of a barely discernible child with a pony tail (or braid) who drapes her right arm over a fence and looks down at the body before her. Faintly silhouetted against a patch of open space, the young girl can easily be missed by all but the most attentive viewers as she blends in with the leafy plants around her.

Once noticed, the child leads the eye to a structure suggested by two sets of vertical lines hiding in the dark recesses of the upper register–perhaps a house. Across the rest of this small patch of verdant landscape, damaged plants and flowers tell a story of struggle and recent destruction in what might have been a well-tended, backyard vegetable garden.

A shadow originating from outside the picture plane on the left ends in a point that meets the prone woman’s right foot and relates to her dark skirt. Cast by a structure with straight edges and therefore of human origin, its top boundary becomes one side of a flattened diamond, the other three edges of which are the overgrown part of the fence that supports the girl, its dark extension to the right, and the left side of the woman on the ground. Ominous in nature, the sharply angled shadow seems a stand-in for the recently-fled rapist.

Following the perimeter of that diamond shape brings the inquisitive observer to the figure’s left hand, the fingers of which curl around the edge of her torn garment near some trickles of blood on her torso and provide the final clue to the story. A peasant woman working in her garden has been raped and stabbed, then left for dead. Hearing the commotion and perhaps some screams, her daughter has come to see what happened and now stares sadly at the sight of her mother, wondering what to do.

Having followed the trail of clues and figured out the narrative, the formerly-naive tourist, seduced by a compelling work of art, has unwittingly entered the empirical world of the connoisseur. Questions tumble forth about the decisions that went into creating the etching. Who was Käthe Kollwitz? What was the Peasant War and why did the artist choose it as a subject? Why did she make a print instead of a painting? If this is a series, what does the rest of it look like? Most curious, why didn’t Kollwitz just tell her story directly and not force her audience to work so hard?

As often happens in exhibits, another visitor approaches and, noticing the engrossed tourist with nose scant inches from the print’s protective glass, engages in conversation about the piece. An art historian by trade, the newcomer eagerly offers information about a favorite artist, her work and her art. An exchange ensues.

First they talk about the etching itself. When the tourist points out the little girl in the background and the trickles of blood near the victim’s left hand, the art historian is surprised, having never before engaged closely enough with the image to notice these elements. More concerned with Kollwitz’s subject matter in general and how it relates to the context in which the artist lived and worked, the art historian appreciated this new insight and resolved to be more attentive in the future to the object itself.

Uprising (1902-03, etching on heavy beige wove paper, 20¼″ x 23⅜″ [51.4 x 59.4 cm]). Plate 5 from the cycle Peasant War. From the 1908 edition of approximately 300 impressions. Knesebeck 70/VIIIb. Private collection. Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY. Familiar with most of Kollwitz’s oeuvre, this knowledgeable viewer knew that Raped was the second plate of seven in the print cycle Peasant War, commissioned by the Association for Historical Art in Germany following submission for consideration of the first completed etching of the series, Uprising (originally called Outbreak).2 In that print, a powerful woman, Black Anna, leads a contingent of fellow peasants armed with makeshift weapons against their feudal lords.3

Revolt (1899, etching on heavy cream wove paper, 11⅝” x 12½” [29.5 x 31.8 cm]). First concept for plate 5 (Knesebeck 70) from the cycle Peasant War. Knesebeck 46/V. Private collection. Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY. The idea for the cycle began in 1899 with a plate Kollwitz etched, variously translated as Uprising and Revolt, that pictured a rag-tag but triumphant mob of scythe-wielding farmers accompanied by a nude woman flying above, carrying a torch from which a flame leaps into the distant background to set ablaze the manor house, home of the oppressors. Coming from a long line of socialists, 4 Kollwitz had already explored the topic a few years earlier in her gold-medal-winning first cycle, A Weaver’s Rebellion.

From childhood, when the young Käthe had enacted barricade scenes with her father and brother, she had imagined herself a revolutionary. It followed that as an artist she would draw strong women into her narratives, depicting them as they sharpened scythes, galvanized men into action, cared for the wounded and identified the dead. When Kollwitz read Wilhelm Zimmermann’s 1841 General History of the Great Peasants’ War and discovered Black Anna, an actual participant in the 1525 revolt by peasants against their overseers, the idea for this cycle was born.

Answering the tourist’s questions about Kollwitz’s choice of printmaking, the art historian explained that after struggling unsuccessfully to master color in her studies at a Berlin academy for women and later in a painter’s studio, and being introduced in 1884 to the work of master printmaker Max Klinger, the young artist finally gave up on painting and in 1890 took up etching, a technique at which she soon excelled. Although Kollwitz later devoted herself to the medium of sculpture, in which she modeled emotionally compelling figurative pieces, she never abandoned printmaking. Expanding her practice to include lithographs and woodcuts, she valued the reproductive capabilities inherent in these mediums, guaranteeing the widest possible audience for her socio-political ideas.

The composition of Raped differs markedly from Kollwitz’s usual images of women who are shown in active roles, not supine on the ground. It is also the only instance where she tackled landscape with enough details to identify cabbage leaves, sunflowers and other plants.5 As for its narrative, in correspondence about this print the artist referred to Raped as “the next to the last plate,” which would have made it the sixth out of seven (though it was published as Plate 2) and described it as “an abducted woman, who after the devastation of her cottage is left lying in the herb garden, while her child, who had run away, looks over the fence.”6

Knowing the artist’s intentions and how she came to etch Raped served only to whet the tourist’s appetite for more information. Just then someone else approached, walking directly up to the two viewers who were blocking access to the print. As chance would have it, the latest arrival turned out to be a psychotherapist who worked with trauma survivors and had a long-standing interest in art depicting sexual abuse and other forms of personal violence.

Käthe Kollwitz, whose work is permeated with meditations on struggle and death, naturally aroused the psychotherapist’s curiosity, especially with respect to how the artist came to focus on those themes. Joining the already in-progress discussion, the clinician related how the printmaker’s son, Hans, had nagged his mother into writing about her life and her development as an artist, and how despite her initial objections, she had surprised him with a manuscript in 1922 that he later augmented with diary entries and letters, and published in 1955.7 Hearing what had already been learned by exploring the image and its creation, the therapist added to the discourse aspects of Kollwitz’s psychosocial history crucial to understanding her choice of subject matter for the etching.8

In recounting her early years, Kollwitz described seeing a photo of her stoic mother holding her firstborn son, “‘the holy child,’” who had died within a year of his birth. Her mother lost a second son before Kollwitz’s older brother Konrad was born. When Käthe was nine, her mother had Benjamin, who also failed to survive beyond his first year, dying from the same meningitis that took the firstborn.

The artist remembered how one night, during her baby brother’s illness, the nurse had burst into the kitchen where her mother was dishing out soup and yelled that the infant was throwing up again. Her mother had stiffened and then went on serving dinner, her refusal to cry in front of her family failing to conceal her suffering from her young daughter, to whom it was obvious.

After that dinner, Käthe–with her younger sister Lise–was sent to play in the nursery where she built with her blocks a temple to Venus and began preparing a sacrifice to a goddess she had learned about in a book on mythology, and who she had chosen to worship over the Christian “Lord”–a stranger to her despite her family’s devotion to him. When her parents walked into the room to convey the bad news that her little brother had died, Käthe was certain “God had taken him” as punishment for her disbelief and sacrifice to Venus.

Because the family’s way was to grit teeth and carry on, with no discussion or even expression of loss and grief, Käthe carried the burden of guilt for her brother’s death into her adult years. Her mother’s unexpressed sorrow suffused their home and her oldest daughter lived in fear that her parents would come to harm.

Stopping the story at that point, the psychotherapist retrieved an ebook reader from a handbag and read from Kollwitz’s autobiography. “I was always afraid [my mother] would come to some harm…If she were bathing…I feared she would drown.” Reflecting on watching through the apartment window as her mother walked by, Kollwitz continued, “I felt the oppressive fear in my heart that she might get lost and never find her way back to us…I became afraid Mother might go mad.”

As the clinician tucked away the ebook reader, the trio of observers turned back to the etching Raped. Suddenly they understood what the artist might not have known herself, that the young girl looking over the fence was nine-year-old Käthe and the woman on the ground was her mother, finally felled by a trauma too insistent to be repelled.

As the three viewers continued contemplating the poignant image before them, another person approached. They eagerly began sharing their recent discoveries as they made room for the newcomer who, noticing the dates of the artist’s life, explained that Käthe Kollwitz was not a twentieth century artist but a woman born, raised and educated in the second half of the nineteenth century.9 Living in Germany in the late 1800s must have affected her art, they all agreed.

But that’s a story for another time.

____________________________________________________

1A print of the etching was displayed for a while in the Drawing and Print Gallery of The Metropolitan Museum of Art several years ago. The work under consideration, a proof, is in the private collection of the writer.

2Martha Kearns, Käthe Kollwitz: Woman and Artist (New York: The Feminist Press at The City University of New York, 1976), 85.

3See Elizabeth Prelinger, Käthe Kollwitz (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 30-39, for a description of the evolution and content of The Peasant War cycle.

4See Jane Kallir, “Käthe Kollwitz: The Complete Print Cycles” (Galerie St. Etienne, exhibit essay, October 8 through December 28, 2013) for additional information about Kollwitz’s print cycles.

5 Hildegard Bachert, “Käthe Kollwitz: The Complete Print Cycles,” gallery talk (Galerie St. Etienne, November 7, 2013).

6Käthe Kollwitz, quoted in Käthe Kollwitz: Werkverzeichnis der Graphik, by Alexandra von dem Knesebeck, trans. James Hofmaier (Bern: Verlag Kornfeld, 2002), 291. Relevant excerpt of text included in provenance documents accompanying the proof.

7The Diary and Letters of Kaethe Kollwitz, ed. Hans Kollwitz, trans. Richard and Clara Winston (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1955).

8See Ibid., 18-20, for information about Kollwitz’s childhood experiences of loss.

9Bachert, gallery talk.

Käthe Kollwitz: The Complete Print Cycles

The Galerie St. Etienne

24 West 57th Street

New York, NY 10019

(212)245-6734

Now till December 28, 2013.

Posted in Art Historical Musings, Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Sunday, August 4th, 2013 Print This Post

Sunday, August 4th, 2013

An Unlikely Master,

Caravaggio Brings Light

To the World of Painting

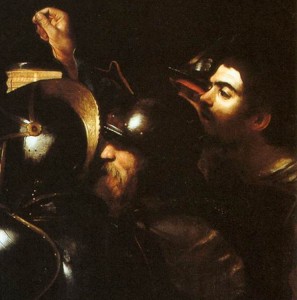

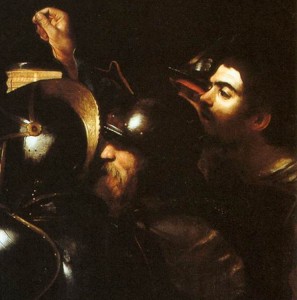

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Taking of Christ (detail) (1602, oil on canvas, 135.5 x 169.5 cm). National Gallery of Ireland. Courtesy of the Jesuit Community, Leeson St. Dublin. Photograph © National Gallery of Ireland. In 1610 in the Italian coastal city of Port’Ercole, at the all-too-young age of 38, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio succumbed to either malarial fever (historically preferred version) or violence (supported by newer research).1 He left behind several paintings on a boat wending its way without him (another story) to his patrons in Rome and more critically, a new way of painting that had already changed the practices of many of his contemporaries, and would continue to inspire artists in the near and distant future.

In the spring of 2013, Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art hosted the final stop on an international tour of the exhibition, Burst of Light: Caravaggio and His Legacy. The multi-venue show, which grew out of a collaboration among the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Atheneum and several French museums, displayed a selection of works by Caravaggio and his many followers that could be seen in its entirety in the finely illustrated catalog but only enjoyed in part at each site.

For the movie-going, novel-reading public, facts and fantasies about Caravaggio’s tumultuous social life might be better known than the significance of his contributions to the practice of figurative painting. Two well-attended gallery talks in the space of a few hours on a beautiful Saturday afternoon in June demonstrated that given the opportunity, a contemporary audience could be captivated by the images that centuries ago first attracted fans.

A visitor asking at the Atheneum information desk for directions to the exhibit was told that straight ahead at the top of the grand staircase was a room with the Caravaggios and on either side of it, ones with the work of other artists. Unlike with the usual blockbuster that sprawls over an endless succession of galleries, the close proximity of these 32 paintings allowed for comparisons among them via a short walk from one to the other.

Only four of the five Caravaggios originally slated for the show were on display. Apparently the Metropolitan Museum of Art had decided to hold onto its jewel, The Denial of Saint Peter (1610), for the spring opening of its new European painting galleries. A late work, the painting demonstrates how far the master had gone in his ability to pick out light from darkness with just a few deftly applied swipes of high-value color.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy (c.1595–96, oil on canvas, 36⅜″ x 50¼″ [92.5 cm x 127.8 cm]). Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut. Caravaggio’s potential to do a lot with a little was already evident fifteen years earlier when he created Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy (c.1595–96). In a three-by-four composition with a sweeping diagonal, an angel with a highlighted bare left shoulder supports the weight of Saint Francis, whose head is thrown back in dreamy contentment as he indicates with his right hand a chest wound similar to the one inflicted on Christ when he was crucified.

In the right half of the painting, Caravaggio’s light draws attention to the action as it lands on the angel’s face, upper body and right hand (which tugs on the rope around the saint’s habit), and Francis’s face and hands. Following the sweep of the brown cloth brings the viewer to a bright spot that opens up the rest of the scene where a man curled in a fetal position leans against a tree and props up his head with his hand, perhaps sleeping, unaware of the drama taking place nearby.

Behind him several much smaller figures gather around the bright spot–a fire–intent on something outside the picture on the left. Further back, light of unknown origin, either from an unseen full moon or a spiritual presence, illuminates a body of water.

The tenderness with which the spiritual being gazes upon and cradles in his arms the ecstatic mortal borders on a far more profane tableau of post-coital bliss. The barely open, unfocused eyes, slightly upturned corners of the mouth, and limp body of the saint remind the viewer of the thin line between religious ecstasy and sexual arousal.

That double entendre was probably not accidental. Caravaggio ran with a wild bunch of like-minded painters in Rome and when not working in his studio to “destroy the art of painting”2 with his rebellious naturalism, managed to repeatedly come into conflict with the law. As unconventional with his sexual behavior as he was with his brush, the great iconoclast enjoyed an intimate relationship with one of his young followers nicknamed Cecco del (as in belonging to) Caravaggio. An accomplished artist in his own right, Cecco modeled for his master and accompanied him on his travels.3

Caravaggio, having lost his father at age six and a brother several years later, sent by the time he was thirteen to live in the house of the painter with whom he apprenticed, then having his mother die when he was nineteen,4 arrived in Rome at age twenty–a young man with a history of many losses and maybe even exploitation. Born in Milan in 1571 as Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, this fledgling artist soon after his mother’s death cashed in his inheritance and headed to Rome where, within the next few years, he found a wealthy supporter and developed a revolutionary style of painting.

Proclaiming Nature as his teacher, Caravaggio painted from life; he found his models among the street people he met on his usual rounds and portrayed them as they appeared–without idealization. Using a single source of light that raked across figures placed in a shallow, dark space without an identifying context, the artist sometimes encountered outright rejection of his in-your-face realism when one patron or another refused to accept a commissioned piece (usually one bound for a church). But the look caught on and others emulated it, though none except perhaps Jusepe de Ribera came close to wielding a brush the way this virtuoso could.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Martha and Mary Magdalen (1595–96, oil and tempera on canvas, 39⅜″ x 53″ [100 x 134.5 cm]). Detroit Institute of Arts. In what was to become that signature style, in another early work, Martha and Mary Magdalen (1595–96), Caravaggio again used light to differentiate between the spiritual and material. Bright spotlighting on the compositionally central Magdalen’s face emphasizes her enlightenment at the same time it draws attention to her cleavage-revealing low-cut dress, a reminder of her former attachment to worldly things. A bright island amid an area of dark colors, her left hand points to an almost pure white rectangle in a mirror that supports her arm. While probably meant to represent the presence of the Divine, the reflection also suggests Caravaggio’s light source: a small (basement?) window high up in an otherwise very dark room.

The curve of Mary’s red-satin-clad right arm leads to a white flower held close to her heart and onwards to the yellow sash that ends at a sponge in a bowl near a comb, all of symbolic value. Open-mouthed Martha, in the midst of a debate with her sister, enumerates her first point with brightly defined hands. Her shadowed face and far more sober attire attest to her attachment to good deeds as the path to spiritual attainment in contrast to Mary’s preferred life of contemplation.

The purple of Mary’s dress, green of the cloth near the mirror, and variety of hues of Martha’s attire, painted in large areas of local color, would continue for a while in Caravaggio’s early paintings and later be supplanted by mostly monochromatic images with an occasional bright red section, perhaps because of the high cost of other pigments.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Salome Receives the Head of Saint John the Baptist (c. 1606–10, oil on canvas, 36″ x 42″ [91.5 x 106.7 cm]). The National Gallery, London. The late work Salome Receives the Head of Saint John the Baptist (c. 1606–10) is a good example of the way Caravaggio eventually distilled his style to a tenebristic scene of light and dark with few hints of color. In a setting lacking description, three half-length figures joined by the head of another are caught in the moment immediately following a decapitation. Looking at something outside the picture frame, Salome turns her head away from the platter she holds on which the executioner places that part of Saint John she had requested, while an elderly, ghost-like woman behind her rests head on clasped hands and looks downward. The grim-faced executioner, with his characteristically Caravaggio light-bathed bared shoulder, extends his arm to deliver Salome’s trophy, as if to create distance between himself and his deed.

Similar in style and format to The Denial of Saint Peter, the Salome seems to have been cut off on the left. A few more inches on that side would bring it closer to the three-by-four proportion of the Denial and other Caravaggio paintings. Also, although identified as Salome, the woman receiving the head is entirely too dressed down to be the seductress of myth.

At this point in his career, Caravaggio painted with light. Notorious for having left behind few if any drawings, he scratched his ideas directly onto a wet underpainting and built upon that with observations from life. In the Salome, unhesitant brush strokes of almost pure white describe the folds in the cloths and pick out the highlights on the cross-like sword. The few notes of warm color can be seen in the slight blush on Salome’s face and in the sun-exposed visage of the executioner, in the still-flushed ear of the saint’s head and the neat little trickle of blood below it, pooling in the dish. The artist’s true genius can be found in his ability to model barely perceptible form in very dark shadows.

Early on, Caravaggio’s rapid rise to artistic prominence in Rome, along with his notoriety, attracted the attention of the many other young artists who had come to the ancient city in search of fame and fortune. Among them was Bartolomeo Manfredi (1582-1622), who adopted his teacher’s tenebrism and half-length figures set in dramatic, often violent, tableaux, and eventually influenced future generations of artists with what came to be known as the Manfrediana methodus.5

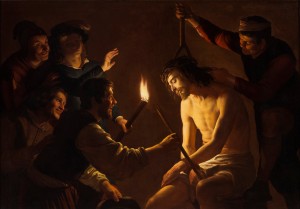

Bartolomeo Manfredi, Christ Crowned with Thorns (c. 1620, oil on canvas, 33″x 44″ [82.6 x 110.5 cm]). Michele and Donald D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, Massachusetts. Caravaggio’s influence on this older artist was especially evident in one of the two Manfredi paintings at the exhibit, Christ Crowned with Thorns (c. 1620). In a zoomed-in view of Christ’s tormentor yanking on a rope that seems to simultaneously force his captive to bend over while at the same time embedding the wreath of thorns securely into the skin, Manfredi emulated Caravaggio’s use of dramatically lit half-length figures–even including a spotlighted bare shoulder–and the latter’s often imitated head-bowed Christ as seen in his The Crowning with Thorns (1604).

Neither Manfredi nor most of the others desirous of cashing in on this much-in-demand new style of painting could approach Caravaggio’s drawing ability and paint handling. Where the master’s brushstrokes demonstrate the same swaggering self-confidence that was his undoing in the streets, Manfredi’s reveal the effort required to accurately render his intentions.

Orazio Riminaldi, Daedalus and Icarus (c. 1625, oil on canvas, 52″ x 37″ [132 x 96.1 cm]). Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut. Another member of the club was Orazio Riminaldi (1593-1630), whose Icarus with open mouth, red lips and come-hither expression in the homoerotic show stopper Daedalus and Icarus (c. 1625) shares an affinity with the lute player in Caravaggio’s The Concert (c. 1595), who presents himself to the onlooker in much the same way.

Ostensibly, Riminaldi has illustrated the myth of the architect of the Labyrinth, imprisoned with his son in his own creation, who fashioned wings from wax and feathers to enable their escape, and is here seen affixing them to the boy, who will fly too close to the sun and perish. Interpreted by some as an allegory of the risks of creative genius,6 the subject affords this artist an opportunity to exquisitely contrast the freshness of youth with the weathered appearance of maturity.

The wrinkled skin on the forehead of the older man, his tan and muscular right arm, and the prominent veins on the hand holding the wing are set against the curly hair, silky smooth pale complexion and less developed musculature of the boy. The brightly lit, perfectly painted flesh of the latter’s thigh, the softness of which is alluded to by the nearby downy feathers, invites the viewer to caress it.

Taking away the wings and the title, one sees a much older man about to embrace a rather fey, nude, prepubescent boy who supports himself with his right arm as he leans back, perhaps in response to the pressure of the other between his legs. Riminaldi discreetly draped a red cloth down the front of the man’s body to avoid the appearance of skin-to-skin contact in the area of the youth’s genitals. The boy’s raised arm, which provides freer access to his body, parallels that of the man’s and avoids direct contact with it.

Riminaldi’s compositions indicate substantial knowledge of Caravaggio’s paintings, primarily via Orazio Gentileschi (1565-1639) and Manfredi but also from Simon Vouet (1590-1649).7 Much more challenging to trace was how Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652) came to incorporate in his own work the tenebrism and brute naturalism of Caravaggism.

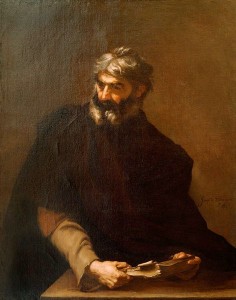

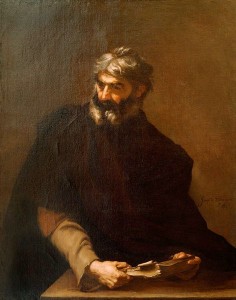

Jusepe de Ribera, Protagoras (1637, oil on canvas, 48⅞″ x 38¾″ [124 x 98 cm]). Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut. A Spanish artist working for a while in Rome and later in Naples–called Lo Spagnoletto by the Italians–Ribera produced a large body of work during his stay in the birthplace of Caravaggism, enough to push back his dates of residence to those contemporaneous with Manfredi and his cohorts (as early as 1604-5), and allow for at least eight of his formative years for absorbing their influence. 8

Tucked away in a small room where visitors could thumb through the exhibition catalog and other relevant books was Ribera’s Protagoras (1637), a prime example of Roman lessons well learned. Luminescent thanks in part to direct lighting, this exquisitely drawn and painted oil places in a nondescript setting a three-quarter length figure whose hands hold a book that abuts the picture plane. Other black-infused canvases from these later years, epitomized by the 1637 Apollo Flaying Marsyas, demonstrate the continued appeal to Ribera of Caravaggio’s use of starkly lit figures in the depiction of suffering, martyrdom and death.

Simon Vouet, The Fortune Teller (c. 1620, oil on canvas, 47″ x 67″ [120 x 170 cm]). National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Another arrival from foreign shores, Simon Vouet (1590-1649) built a very successful career in Rome by cashing in on the Caravaggism craze, initially with portraits of spotlighted subjects and later with amusing genre subjects like The Fortune Teller (c. 1620), the subject of which was popularized by Caravaggio with at least two versions of The Gypsy Fortune Teller (1595). In these scenes, costume-clad characters enact comical scripts of chicanery for the entertainment and perhaps instruction of the viewer, not unlike theater performances.

In Vouet’s reading, the shining smile of the fancily dressed woman on the right, who makes eye contact with the audience, directs attention to the unfolding events. An astounding interplay of five hands in the center of the composition distract the eye from the missing three hands of the expected eight possible among four actors.

The scruffy looking guy with the strange mouth rests his right hand on the lady’s shoulder in a too-familiar gesture, points at her with his other hand, and looks toward the other man who raises a finger in a just-a-moment pose while ransacking the gypsy’s shoulder bag for means of payment. The lack of jewelry (other than a simple ring) on the well-dressed woman adds yet another clue that she is not some wealthy woman visiting a poor neighborhood to find out her future. The fortune teller seems poised to drop a coin into the extended hand while looking across at its owner with the slightly raised eyebrows of curiosity and expectancy.

Lest anyone miss the joke, Vouet painted a red sash on the brown-skinned woman’s bag, leading the eye straight to the action. Likewise, the high-value white of the fortune teller’s blouse in contrast with the dark tone of her skin draws focus to the right side of the painting and the man in the shadows behind her. Each facial expression adds to the drama played out by three-quarter length figures set close to the picture plane in an indeterminate setting lit in typical Caravaggesque fashion.

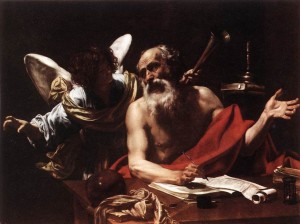

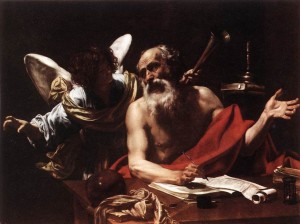

Simon Vouet, Saint Jerome and the Angel (c. 1622, oil on canvas, 57″ x 70″ [144.8 x 179.8 cm]). The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Picking up on another well-known Caravaggio theme, Vouet painted his own Saint Jerome and the Angel (c. 1622), a tour de force of gesture and facial expression with even more dramatic lighting accenting the action. The same red garment, exposed torso, balding head and white beard that characterize the protagonist in Caravaggio’s Saint Jerome Writing (c. 1606) appear in Vouet’s rendition of the story. The debt to his predecessor is further evident in the angel’s right hand, which takes its pose from the left hand of the Boy Bitten by a Lizard (1595), an early painting by Caravaggio.

Arriving trumpet in hand to announce to Jerome his imminent death, the curly-haired angel with its sweet smile of compassion encounters the busy scholar in the midst of his work transcribing ancient Greek and Hebrew biblical texts into Latin.9 Jerome turns from his work, makes eye contact with his visitor and raises his left hand as if to say, “Give me a break! I’ve barely made a dent in this stuff.”

Vouet choreographs the figures within a diamond shape, the top point of which is the angel’s left wing and the bottom the foremost corner of the table, lying just beyond the picture plane. All but one of the their combined four arms synchronize with each other in their movement upwards. The rebellious exception remains adamantly planted on the desk, its hand poised to continue writing if given the chance.

Despite wrinkles, receding hairline and long white beard, Jerome sports the musculature of a much younger man. The red drapery against which his left arm must work to achieve levitation serves to define part of the lower left side of the diamond while doing nothing to cover that by-now-familiar, well-lighted, bare male shoulder.

Some of the abilities that made Vouet so successful in Rome are apparent in his modeling in the dark of the angel’s face and his skill in rendering a great variety of textures, especially the characters’ hair and skin. Never fully wedded to Caravaggism, however, this artist went on to paint in other styles.

Nicolas Tournier, The Denial of Saint Peter (c. 1625, oil on canvas, 63″ x 94″ [160 x 240 cm]). High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia. In contrast, Nicolas Tournier (1590-1639) completely adopted the current fashion of painting in Rome when he arrived there sometime around 1619 10–quite obvious in The Denial of Saint Peter (c. 1625), his one work in the exhibit. Eager to demonstrate his skill at depicting the prevailing themes among the Caravaggisti, Tournier combined two separate stories in his one large canvas.

On the left, Peter denies to the soldier about to arrest him that he knows Christ. On the right, another soldier watches three colorfully dressed men in a game of dice. The beautifully painted sword that adorns the one in the skin-tight leggings and blousy, yellow shirt, and the hilt of another peaking out from the dice player who stares with wide-eyed, open-mouthed alarm at the events unfolding nearby, bring to mind the artists who originally ran with Caravaggio; they also carried blades and often got into street brawls. Perhaps Tournier’s idea was to show on one side a biblical scene a la Caravaggio and Manfredi, and on the other, the artists who looked closely at their work.

This multi-figured composition contains plenty of action along an arc that begins with the head of the sleeping disciple on the left and travels through all the heads to the back of the young man on the far right. Tournier adeptly portrays facial expression and packs into the painting lots of opportunity to display his talent for depicting texture, from hard, shiny armor to coarse cloth, and throws in a pail of very convincing burning coals for viewers’ enjoyment. While his artistic model was Caravaggio, unlike the master, Tournier applied paint in thin and carefully applied layers to slowly build up form and define surfaces.

Francisco de Zurbarán, Saint Serapion (1628, oil on canvas, 475/16″ x 4015/16″ [120.2 x 104 cm]). Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut. A Spanish artist with a much thinner connection to the crowd in Rome, Francisco de Zurbarán (1598-1664) might have been chosen by the Atheneum’s curators because a stunning example of his work, Saint Serapion (1628), already hung on their walls. Studying in Seville when awareness of Ribera’s work ran high, 11 he seems to have incorporated the tenebristic lighting of Caravaggism, if little else.

Zurbarán brilliantly summarizes the martyrdom of Serapion–by crucifixion, beheading and quartering–in the pose. The slumping saint’s body held up by ropes that fix his outstretched arms above his head represents death on the cross. His head falling to the side, disconnected from his body by the hood of his habit, suggests decapitation. And the securely tied rope around his right wrist references his quartering.

Lacking the usual bloody drama of Caravaggesque martyrdom scenes, Zurbarán’s almost square composition provides a sense of stability. His placement of the saint’s head in repose on his right shoulder and the calm look on his face have little in common with the theatrics found among other works in the exhibit.

By affixing to the canvas with a tromp l’oeil pin a torn scrap of paper with his signature in ultra thin lettering, and rendering the red and yellow shield of Serapion’s monastic order in a decidedly unrealistic fashion, Zurbarán calls attention to the artifice of painting. Unlike the three-dimensional drapery folds, and the hands and head of the figure, the shield–with its central placement and sole use of color in this monochromatic picture–loudly calls attention to the two-dimensional nature of the canvas by appearing to float on the picture plane rather than be attached to the robe.

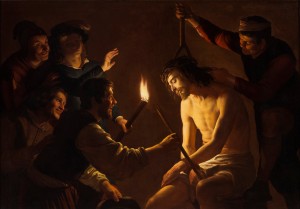

Gerrit van Honthorst, Christ Crowned with Thorns (c. 1617, oil on canvas, 51⅜″ x 67⅜″ [146 x 207 cm]). Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Unlike Zurbarán with his attenuated connection to Caravaggio’s circle of followers, Gerrit van Honthorst (1592-1656) lived and painted in Rome starting in 1616. Part of a small community of other Dutch artists, he quickly adapted the latest style of painting, especially apparent in Christ Crowned with Thorns (c. 1617), one of three of his paintings in the exhibit.

Taking compositional ideas from Manfredi and company, particularly in his choice of subject matter,12 tenebristic lighting, undefined background and zoomed-in view, van Honthorst followed his own path in the material execution of the painting. Figures are contained within their own contours. Fabrics are devoid of identifying details. And brushstrokes are barely detectable. He differed too in his choice of body types for his figure of Christ, which lacks the buff male body with its bared shoulder(s) so popular among the Roman crowd.

Instead, van Honthorst’s mocked man, with sad resignation, gracefully submits to the humiliation and physical pain being forced upon him; though he bows his head, he doesn’t resist the thorns being implanted there. Slightly slumped forward, Christ accepts the stick placed in his hand by one of his tormentors, a man whose open-mouthed laugh, wrinkled brow and wide-open eye express a sadistic enjoyment rarely depicted among Christ’s torturers.

Georges de La Tour, Old Man (c. 1618–19, oil on canvas, 35⅞″ x 23″ [91 x 60.5 cm]). The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, California.  Georges de La Tour, Old Woman (c. 1618–19, oil on canvas, 35⅞″ x 23″ [91 x 60.5 cm]). The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, California. Awareness of the work of northern European artists like van Honthorst contributed to the spread of Caravaggism beyond the Alps and might have been how Georges de La Tour acquired knowledge of this new way of painting. Whether or not he ever made it to Rome remains indeterminable and his inclusion seemed like an afterthought, quite literally since his were the last three works in the exhibit.

Unlike the first of those (de La Tour’s much later candlelit scene of The Magdalen with the Smoking Flame [1638-40]), the other two–a pair of full length figures, Old Man and Old Woman (c. 1618–19)–were far from Caravaggesque. These striking portrayals of an elderly couple lack most of what had come to be associated with artists inspired by the works of Caravaggio.

The man, whose painting was displayed to the left of the woman’s, supports his weight on a walking stick, leans over as if to peer around the picture frame, and casts a sidelong glance at the woman in the other picture. The object of his gaze stands with hands on hips–perhaps removing the apron that falls away as her left hand slips under it–and looks back at him with her mouth open, as if in midsentence.

De La Tour made the man the more colorful subject, with his green jacket, orange-red pants, yellow leggings and suntanned skin, and indicated his age with a bald head, grey hair, white beard and need for a stick to prop him up. For the woman, the artist used stark white for her hat and blouse without benefit of modifying colors, a flat green with revealing bits of brown underpainting for the bodice of her dress, and a golden hue for the fold-creased apron that covers most of a burgundy skirt, a sliver of which turns lavender under the light on the left. Giving her far fewer wrinkles than her mate, the artist somehow still managed to convey her seniority.

In each painting, de La Tour made the background dark for the lighted area of the figure and lighter for the shadowed side. The man’s right leg hides the point where diagonal lines meet convincingly to indicate a corner at the base of the walls. The woman’s body covers most of the edge where dark walls meet light ones, but the horizontal line running along their base would destroy any illusion that this is a corner were one to look too closely at it. In his skillful rendering of an elderly woman in the midst of an interaction, de La Tour manages to provide enough distractions for the viewer not to notice.

The inclusion of de La Tour in an exhibit on Caravaggism demonstrated just how far afield Caravaggio’s groundbreaking approach to figurative painting reached, extending its spread throughout Europe over the next few hundred years. One man’s impulse to transmute his inner turmoil into art resulted in a new way of constructing images, one still practiced in the present by artists who place emotionally expressive, ordinary characters within tenebristically lighted settings, and assign them roles in emotionally and/or spiritually significant stories, hoping to engage their audience in the contemplation of the often violent drama of human relationships.

_________________________________

1 Spike, John T. Caravaggio (New York: Abbeville Press, 2001), 239.

2 Papi, Gianni. “Some Reflections and Revisions on Caravaggio, His Method, and his ‘Schola’” in Caravaggio and His Legacy, ed. J. Patrice Marandel (New York: Prestel Verlag, 2012), 14.

3 Ibid., footnote 21, 30-31.

4 All biographical information from Spike, Caravaggio.

5 Marandel, J. Patrice. “Caravaggio and His Legacy” in Caravaggio and His Legacy, 13.

6 Zafran, Eric. “Orazio Riminaldi, Daedalus and Icarus” in Caravaggio and His Legacy, 62.

7 Ibid.

8 Papi, 24-26

9 Exhibit object label.

10 Caravaggio and His Legacy, 78.

11 Ibid, 109.

12 Ibid, 118.

Burst of Light: Caravaggio and His Legacy

The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

600 Main Street

Hartford, Connecticut 06103

(860) 278-2670

Catalog available.

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Sunday, June 2nd, 2013 Print This Post

Sunday, June 2nd, 2013

In Search of George Bellows

Self Portrait (1921, lithograph, 10½″ x 7⅞″ [26.67 x 20 cm]). Collection of Max and Heidi Berry. Courtesy Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Photograph by Ric Blanc. In his 1921 lithograph, Self Portrait, George Bellows poses in formal attire: white shirt with link-adorned cuffs, bow tie and large-buttoned jacket. Calling attention to the artistic process, he includes the mirror that reflects back his image and draws the sketchbook in which he works. His proper right hand–the one that would hold the lithograph crayon and here holds a cigarette–casually rests on something, perhaps the back of a chair.

The 39-year-old Bellows of this self-portrait, concentrating intensely on the task at hand, had already achieved major recognition and can be forgiven for such self-aggrandizement. He shows off not just with his fancy clothes but also with the way he plays with space, from the mirror frame as picture frame and the placement of the artist in the viewer’s space to the background view of a terrace or window overlooking an outdoor scene–beyond the artist and behind the viewer.

This sophisticated urbanite, who in the following year would have the resources to build his own house in Woodstock, New York, began his career with far more earthy fare. Born in 18821 in Columbus, Ohio, Bellows dropped out of college there in 1904 and headed to New York City to pursue an art career. Checking into the YMCA and wandering around the city, he discovered a demimonde that became the subject of his art for a number of years. He was encouraged by his teacher, Robert Henri (pronounced hen-rye), who espoused a manner of working (practiced by a group of artists who came to be known as the Ashcan School) that began with the inner spirit and reached out to encompass the grit of life.

Turn-of-twentieth-century New York City provided abundant material for artists bored with classical subject matter. For Bellows, it was its teeming hoards. Children on the streets and in the rivers seeking relief from overcrowded tenements, crowds in Times Square waiting for results on election night, and spectators at sporting events and revival meetings, all came to life in his drawings, paintings and prints as he set out to establish his artistic identify.

Kids (1906, oil on canvas, 32″ x 42″ [81.3 x 106.7]). James W. and Frances G. McGlothin. © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Photograph by Katherine Wetzel. The painterly canvas Kids (1906) was among the earliest of Bellows’s paintings on display at a ten-room retrospective held during the winter of 2012-13 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, organized in association with the National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC) and Royal Academy of Arts (London). The first comprehensive review of the artist’s work in over 30 years, the exhibit gave the viewer an opportunity to track Bellows over time as he struggled to find the perfect way to conceptualize, construct and execute a work of art.

In Kids, Bellows quickly sketched a scene of children hanging around, tussling with each other, sharing some food, smoking and on the left–emphasized by highlighting on a street cart behind him, a boy painting a wooden object, perhaps destined to be a wagon. Bellows’s adept draftsmanship guides his sure application of paint as he craftily relates the two discreet groups by having the blond girl in the white dress and her canine companion stare at the action to their left. These are not portraits of individuals so much as they are portrayals of types engaged in defining activities.

River Front No. 1 (1915, oil on canvas, 45⅜″ x 63⅛″ [115.3 x 160.3 cm]). Columbus Museum of Art. In Bellow’s time, the New York waterfront–of which there is plenty–hosted large groups of swimmers from all socioeconomic classes depending on the level of amenities provided. For children looking to escape overcrowded Lower East Side tenements in the sweltering summer, the broken-down piers and under-development docks became their beaches. Where they went, Bellows followed.

Forty-two Kids (1907, oil on canvas, 42¼″ x 60¼″ [106.7 x 153 cm]). Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington. Photograph by Mark Gulezian. Like Thomas Eakins’s not-so-innocent composition of six male Swimmers (1884-5), Forty-two Kids (1907) is a pedophile’s paradise. Mostly nude, young boys in assorted poses unabashedly bare their asses to an unseen audience and frolic among themselves, in and out of the water. Bellows’s voyeuristic fascination with males naked together finds a reprise in the more upscale oil, River Front No. 1 (1915) and the later lithograph, The Shower-Bath (1917), the latter perhaps a revery on his brief stay at the YMCA.

With the boys indicated by just a few strokes of color, in Forty-two Kids Bellows massed the figures on the left side of the dilapidated dock to open up the space on the right, directing the eye through the diver to the swimmers, the dark river and the rowboat in the background. Were one to trace the strong diagonals of the wooden planks and draw the horizontal and vertical lines where they intersect, one would glimpse the underlying geometry that already had Bellows in its thrall.

Spontaneity in paint application would ultimately lose ground to a driving need for structure–and perhaps legitimacy–that eventually drained the life from much of this gifted artist’s work. Bellows succumbed to untreated appendicitis at age 42 when some of his work held hints that he might once again throw paint freely. Nonetheless, for connoisseurs of the less fettered work, the exhibit at The Met offered much to admire.

Paddy Flannigan (Winter 1908, oil on canvas, 30¼″ x 25″ [76.8 x 63.5 cm]). Erving and Joyce Wolf. Chief among those paintings was a Ribera-like portrait of one of the street kids who posed for Bellows. Intentional or not, Paddy Flannigan (1908) pays homage to that old master’s portrayal of St. Jerome (1640) with its exposed flesh, semi-draped upper torso and elongated brushstrokes that follow the length of the arm. While Jusepe de Ribera’s saint–poised to pound his chest with the rock he grasps–turns his eyes heavenward, Bellows’s street urchin looks out at the viewer/painter from under almost-closed lids; with one hand on his hip and the other in his lap, this young model broadcasts both an invitation and a challenge.

Bellows infused the face with sun-toned red and gave Paddy’s ear the same color as the drapery he holds. Here again, underlying what appears to be a free-wheeling application of paint reminiscent of other American portraitist of that time (think John Singer Sargent and Cecilia Beaux), a geometric system determined the placement of the arms and the cut of the torn shirt in relationship to the frame of the composition.

Robert Henri extolled the virtues of “a thorough knowledge of geometry” for “the artist whose ideas are to be expressed in apparently magical proportions.”2 Following his teacher’s suggestion probably came easily for Bellows, who seemed to find renewed inspiration from every freshly encountered scientific theory about color and composition, though after a while each new ideology proved insufficient to carry him through self-doubts and frustrations about his work.3

Regarding composition, Bellows drew from a long history of proportional schemes,4 including rebatment, the Golden Section and its close relative, the Fibonacci Spiral. Likewise, he could choose among a plethora of approaches on setting up the perfect palette, one guaranteed to insure repeated success.

In his early explorations of composition and color, Bellows’s inner vision remained paramount as he trawled the streets of his newly adopted city in search of subjects. He must have found irresistible the eight-acre pit covering more than two full blocks that began to appear in midtown the same year the artist arrived in New York. By 1909, the hole was occupied by Pennsylvania Station, a magnificent beaux-arts building later sacrificed for a succession of structures culminating in the current eyesore.

A major attraction for both complaint and celebration, the magnificent feat of engineering that became the first Penn Station served as the foundation for several oils in The Met’s exhibit, the best among them being Excavation at Night (1908). The image is a masterpiece of composition but like any fine painting, the thought behind it takes a back seat to its visual lushness.

Bellows masterfully uses light to direct the eye from the brightly illuminated wall–white on the right and steamy blue on the left–contrasting with and leading to the warmly lit tenements in the background, the orange and yellow of which brings the eye to the foreground and the fire where workers attempt to get warm. Once here, the gaze finds the other light spot in the front, a patch of snow on the left from which a track travels back to streaks of snow in the middle ground that lead right back to the cliffs.

In Excavation at Night, it’s easy enough to see the rebatted squares. Measure the horizontal length along the bottom from first one lower corner and then the other. Where each point falls imagine a vertical line ascending from it. Notice the way Bellows has arranged the composition to fit those vertical lines.

Pennsylvania Excavation (1907, oil on canvas, 33⅞″ x 44″ [86 x 111.8 cm]). Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton. In another view of the pit, Pennsylvania Excavation (1907), the emphasis seems to be on diagonals forming a diamond shape that, along with the bright white steam originating from behind some massive machinery in the foreground, brings the onlooker right down into the belly of the beast. Deploying a nearly monochromatic palette, Bellows conveyed the shivering grey cold of the city in winter. In the lower right, set against a triangle of bright snow, two men bundled up in stone-hued clothing work at something in the ground, their size an indication of the distance separating them from the laborers below.

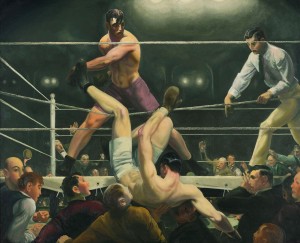

In both excavation canvases, Bellows seems to have reveled in the application of paint, with a variety of brush and palette-knife strokes. That same freedom was evident in his first fight paintings, one of the best–Stag at Sharkey’s (1907)–was featured in the publicity for the retrospective and on the catalog’s cover.

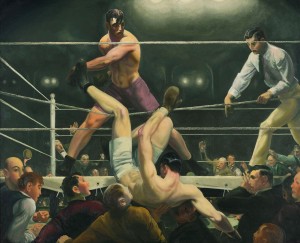

Stag at Sharkey’s (1909, oil on canvas, 36¼″ x 48¼″ [92 x 122.6 cm]). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Hinman B. Hurlbut Collection. The usual four seconds most viewers accord a painting reveal a dynamic composition of two fighters going at it amidst male spectators attentively following their moves, perhaps anticipating the illegal knee to the groin that Bellows’s choreography implies and the referee seems to expect. A more sustained engagement reveals the underlying isosceles triangle with its left edge running from the right fighter’s head down through the left fighter’s leg and the other edge going down through the left arm of the referee. The three-by-four ratio of the outer dimensions lends itself to other geometric manipulations that Bellows used and can be ferreted out by any interested reader.

Peering over the ring’s canvas on the far side to the right might be Bellows looking up from his sketch pad,5 identified by his balding pate. To capture the action, he needed his expert drawing skills, quite apparent in the persuasive way the figures occupy space and interact. Notice especially the foreshortened raised legs and how each fighter balances perfectly on the limb that supports his weight.

Despite its appeal, Stag at Sharkey’s suffers from Bellows’s too heavy reliance on white; colors lose their intensity in the lights. Here as in his other crowd scenes, faces look more like caricatures than those of real folk. An image best viewed from a distance, this glimpse into the once not-quite-legal world of boxing still pulsates with the frenetic energy conveyed by Bellows’ brushstrokes and composition.

Dempsey and Firpo (1924, oil on canvas, 51″ x 63¼″ (129.5 x 160.7 cm]). Whitney Museum of American Art. Photograph by Sheldon C. Collins. The same can’t be said for Dempsey and Firpo (1924), a late work completed in the year before Bellows died. With a drawing style evocative of comic book art, using formulaically applied colors in a compositional schema so obvious as to command more attention than the action (triangles galore, diagonals and verticals relating to rebatted squares), Bellows seems to have lost his way in pursuit of perfection in both art and life.

The Studio (1919, oil on canvas, 48″ x 38″ [121.9 x 96.5 cm]). Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. The artist exposes his craving for an orderly, middleclass life along with his working methods in the stage-set painting, The Studio (1919). Here in a spotless work space, his two daughters sit among their newly opened Christmas presents while their father, decked out in white shirt, jacket and cuffed slacks, rebats the square and draws the diagonals that will underpin his portrait of their mother (Emma) who, clothed in an evening dress, sits raised on a model’s platform.

In the upper register, Bellows’s printmaker works a printing press on a balcony from which hang red and green drapery (the complementary colors of the season) and a spotted wildcat’s hide. In the background, Emma’s mother holds the phone to her ear while a dark-skinned servant looks on, as if awaiting instructions.

The organized mess of the earlier work has disappeared. Growing success and its attendant financial rewards couldn’t compete with Bellows’s feelings of inadequacy. He seemed driven to infuse his work with the gravitas he associated with great art, and many of the later paintings displayed in the last two galleries of the retrospective suffer from it. In trying too hard, Bellows only succeeded in producing deadeningly serious paintings.

Emma at the Piano (1914, oil on panel, 28¾″ x 37″ [73 x 94 cm]). Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk. © Courtesy of the Bellows Trust. Contrast, for example, Emma at the Piano (1914) with Emma and her Children (1923), a portrait done almost a decade later. The earlier, far more colorful painting is a tenebristic study in blues that draws attention to the exasperated Emma’s face. A slightly lower-valued arm leads the eye to the keyboard, where bright white defines the edge of the keys and highlights the hand striking a chord.

The inclusion of Emma’s left hand in her lap and the tension inherent in the twist of her torso as she turns to face her husband belie the spontaneity that the setup implies of Bellows’s interrupting his wife in the middle of practicing; in fact she looks uncomfortable in that position. Although Emma might not be animated, the brushstrokes are–especially the ones vaguely defining the flowers in the vase that’s centered behind the music back.

Emma and her Children (1923, oil on canvas, 59¼″ x 65⅜″ [150.5 x 166.1 cm]). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photograph © 2012 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Discomfort also inhabits Emma and her Children in the stiffness of the poses and the expressions on their faces. Bellows’s wife and two daughters, twelve-year-old Anne and eight-year-old Jean, are here dressed in the antique clothing the artist came to favor–and each seems in a world of her own. Emma sternly/sadly casts an inward glance in the general direction of her serious-looking youngest child who almost makes eye contact with her father. The older girl, the unhappiest among the pictured family, gazes toward her little sister and holds a fan in one hand while trying to figure out what to do with the other.

Using an almost monochrome palette and reined-in brushstrokes, Bellows has done an exquisite job of rendering a variety of textures, including hair, fabric and the wood of the settee. Less successful is the placement of the figures in their respective seats. In particular, Jean’s legs, bent at right angles, are more indicative of the chair upon which she sat for the artist’s study than of a heavy eight-year-old’s sitting on her mother’s lap.

Mrs. T in Cream Silk, No. 1 (1919, oil on canvas, 48″ x 38″ [121.9 x 96.5 cm]). Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington. On his way from the relative openness of Emma at the Piano to the stilted Emma and her Children, Bellows tried his hand at other portraits. For Mrs. T in Cream Silk, No. 1 (1919), the artist requested the sitter, a socialite he’d met while teaching in Chicago, to pose in her 1863 cream silk wedding gown 6 in keeping with his fascination with vintage clothing, perhaps as a way to create a link between his art and that of the old masters.

Mrs. T maintained her wasp-waist figure but the aged skin on her face and neck offers stark contrast to the youthful dress she wears, the skirt of which still bears the fold marks from its time in storage. Looking off to the side, just short of eye contact with the artist, Mrs. T holds a fan in one of her white-gloved hands, the rendering of which is not entirely convincing. Bellows has smoothed over not just the now-concealed wrinkles of those hands but also almost all the creases in the gloves’ fabric, lavishing on them little of the brushstroke bravura so liberally distributed across the rest of the canvas.

The bowl of fruit on the sitter’s left includes a pineapple’s crown and perhaps a mango, both tropical in origin. On her other side, on a bright orange tablecloth, rests what looks to be the base of the corsage she would have held on her way to the altar. A bookcase and its contents blend into the dark background and a patterned gold-and-black cloth hanging behind her brings to mind those behind the Virgin in early Renaissance images. Bellows was clearly making a statement about the passage of time, though once again he might have overdone it.

The same can be said for a great deal of the art he created in 1918 in response to reports of atrocities committed by Germans during The Great War. Many of these–some paintings, but mostly drawings and lithographs–were part of this panoramic retrospective that demonstrated the wide array of subjects that Bellows tackled. Pieces like The Barricade (1918) are overwrought while others like the lithograph Murder of Edith Cavell (1918) show what Bellows could accomplish when he got out of his own way.

In other rooms the artist’s prodigious drawing skills and sensibilities were on view in several highly political pieces, including the lithograph Electrocution (1917) of a man being executed, and both the preparatory drawing and lithograph for The Law is Too Slow (1923) of a black man being burned alive by a lynch mob. These contrast dramatically with paintings in other rooms of tennis matches set among the well heeled.

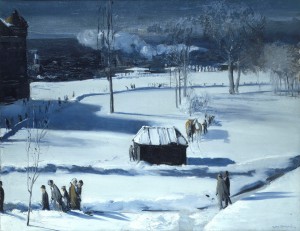

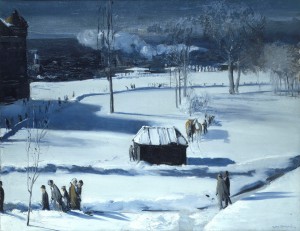

Blue Snow, The Battery (1910, oil on canvas, 34″ x 44″ [86.4 x 111.8 cm]). Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio. In the last room of The Met exhibit hung an oil sketch, My House, Woodstock (1924), that seemed an attempt by Bellows to find his way back to brighter colors and freer paint application. It pales in comparison with Blue Snow, The Battery (1910), one of his many accomplished landscapes displayed in the first part of the show.

The icy blue monochrome of the wintry scene is sparingly punctuated by the orange in the blankets on the horses and in the faces of the pedestrians in the foreground. With an economy of means, Bellows used color and form in Blue Snow, The Battery to create a sweeping view of shivering-cold lower Manhattan, peopled by passersby intent on reaching some destination or just out for a stroll.

In the shadow side of the structure in the visual center of the painting, the viewer gets a peek into Bellows’s working process. A thinly applied underpainting of brown (also evident in the shaded large building in the left background) was brushed away to denote the horizontal boards of the wall. Thick, opaque, high-value color was applied throughout to reflect the crystal-clear light of winter. The geometries that the artist certainly used in devising his composition dissolve in the wonder of how simple marks, placed expertly, can come together to form such a believable picture.

In his best work–from disheveled street urchins, New York’s dock workers and its resident poor, to well-dressed ladies and gents in other wintry settings, and landscapes of the city’s changing faces–George Bellows was at his best at the beginning of his career before the ordinary self-doubts inherent in the life of any artist overwhelmed him, compelling him to pursue techniques ill suited to his nature. He died in 1924 at the age of 42 before he could find his way back home.

__________________________________________

1 All biographical material comes from Quick, Michael, et al. The Paintings of George Bellows. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1992).

2 Henri, Robert. The Art Spirit (1923). (New York: Basic Books, 2007), 155.

3 Quick, Michael. “Technique and Theory: The Evolution of George Bellows’s Painting Style” in The Paintings of George Bellows.

4 See Bouleau, Charles. The Painter’s Secret Geometry: A Study of Composition in Art. (Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1963).

5 Exhibit wall text.

6 Ibid.

George Bellows

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue (at 82nd Street)

New York, NY 10028

(212)535-7710

Catalog available.

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Sunday, January 6th, 2013 Print This Post

Sunday, January 6th, 2013

Breaking the Code:

Jane Kallir Deciphers

Egon Schiele’s Images of Women

Self-Portrait with Long Hair (1907, oil on canvas, 14″ x 11¼″ [35.5 x 28.5 cm]). Private collection. Once upon a time there was a little boy named Egon who loved to draw. He lived in fin-de-siècle Vienna with his mother, father and two older sisters, Elvira and Melanie. 1 When Egon was three years old, ten-year-old Elvira died from meningitis. A year later his baby sister Gertrude (Gerti) was born.

The story of how Egon’s parents got together was typical for those times. When his father Adolf was 23 he fell in love with twelve-year-old Marie but waited till she was seventeen to marry her. Having contracted syphilis some time before then and refusing to have it treated, Adolf soon gave it to his new wife. Because of complications from her conjugally acquired venereal disease, Egon’s mother suffered three stillbirths before she had her first live baby, Elvira, whose later death probably resulted from the syphilis passed on to her at birth.

By the time Egon was twelve, his ill father’s behavior had become unpredictable and violent, symptoms of his end-stage syphilis. On one occasion, the increasingly erratic man “set fire to all of [his son’s] carefully executed railroad car drawings.”2

“Following a final fit of madness that involved a suicide attempt and the burning of all of the family’s stock certificates,”3 Egon’s father died. The relief that the fourteen-year-old boy must have felt could not have lasted long. The uncle enlisted by his mother to share guardianship of her two minor children (Egon and Gertrude), forbade the talented child from pursuing an art career.

Egon’s school performance had suffered greatly during his father’s decline and, after another couple of years of lackluster grades, the young teenager left school under threat of being held back. In 1906 his mother, against his uncle’s dictates, enrolled Egon in the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, where the rebellious sixteen-year-old who had been drawing independently for many years, collided with the regimentation of its classic academy curriculum, though not before acquiring some useful drawing techniques.

Portrait of a Lady in Profile Facing Right (1907, charcoal on paper, 20⅝″ x 13⅝″ [52.4 x 34.6 cm]). Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne. To qualify for admission to the Academy, Egon submitted portraits of women he encountered in his day-to-day world: his older sister, his mother and a maid. The style was not unlike Portrait of a Lady in Profile Facing Right (1907), one of his student drawings. At seventeen, Egon drew with the confidence and skill of a master, able to capture subtleties of texture, from the model’s fur wrap to her smooth, young skin.

After two years of butting heads with one professor in particular, Egon stopped regular attendance at the Academy and sought other sources of inspiration. He had plenty to choose from, gravitating toward Gustav Klimt and his fellow Austrian Expressionists, as well as a bevy of other contemporary artists breaking new ground elsewhere in Europe.

Self-Portrait with Arm Twisted Above Head (1910, watercolor and charcoal on paper, 17¾″ x 12½″ [45.1 x 31.7 cm]). Private collection. Courtesy Neue Galerie, New York. Fifteen years later another young man with a taste for Expressionism opened the Neue Galerie in Vienna with “the first posthumous Egon Schiele retrospective.” 4 During the years that this gallerist, Otto Kallir, maintained his exhibition space, he continued to champion Schiele and his cohorts. When Hitler’s invasion of Austria forced Kallir to emigrate to the United States in 1939, he set up shop in Manhattan, opening the Galerie St. Etienne with Hildegard Bachert. 5

When Otto died in 1978, his granddaughter Jane Kallir inherited not just the gallery but also a passion for the art of Austrian and German Expressionists, especially that of Egon Schiele, about whom she has written tomes. The publication of her latest volume, Egon Schiele’s Women, a coffee-table-sized book lavishly illustrated with over 200 high-quality reproductions of the artist’s drawings and paintings, was well timed to coincide with the similarly titled exhibition at Galerie St. Etienne.

In the book and the essay accompanying the exhibit’s checklist, Kallir positions Schiele within the particular milieu that was turn-of-the-twentieth-century Vienna, where Darwin’s theory of evolution, Freud’s uncovering of the unconscious, and women’s new opportunities for participation outside the home (thanks to industrialization) threatened the previously entrenched patriarchy. The backlash unleashed by the established order in reaction to those threats still reverberates down through the decades, blinding investigators in all fields to a reality possible in Viennese (and all other) families that for a while Freud and some colleagues could not ignore.

In 1896, the founder of psychoanalysis presented an earthshaking paper “The Aetiology of Hysteria”6 to an audience of esteemed Viennese doctors, in which he described eighteen case histories of mostly women whose symptoms now fit the criteria for post-traumatic stress and dissociative disorders. “[A]t the bottom of every case of hysteria there are one or more occurrences of premature sexual experiences…[that] belong to the earliest years of childhood,”7 he declared, going on to say that in most cases the aggressor was the father. (Emphasis in original.)

Cowed by the ostracism such blasphemy engendered, Freud soon began backtracking and within a few years had repudiated his original observations. In its place grew his convoluted theory of infant sexuality, part of which entailed the girl child’s lusting after her father and developing sexual fantasies about him, the later repression of which during adolescence accounted for her acute psychological distress. On a parallel track, other doctors had determined that children were, by nature, pathological liars, effectively eliminating the need for adults to pay any attention to reports of childhood sexual assault.

Kallir references a variety of other contemporary writers who likewise endeavored to demonize women’s sexuality. Some believed the female sex’s primal nature–a morass of urges that had to be contained–to be the antithesis of male’s rationality. Others insisted that proper bourgeois women had no interest in sex at all, relegating such desires to the lower classes. One popular belief held that premarital masturbation by women led to neuroses.

By sequestering adolescent upperclass girls, society protected the guarantee of their virginity, if not necessarily the fact of it. Boys like Egon, who were denied sexual access to them until reaching sufficient financial maturity to marry (usually in their mid-twenties) could in the meantime avail themselves of prostitutes. Demand drove supply and Vienna became “the capital of European prostitution,”8 with women of the lower classes filling the many openings created by the myth of the asexual bourgeois female. Within that societal context and his more immediate family environment, Egon traversed his adolescence.

Once the teenager left the Academy, he needed to secure his own models. At home, continuing his habit of using family members as subjects, he turned to his vulnerable younger sister. By the time she was thirteen, Gerti had become her older brother’s favorite model, frequently posing for him in the nude. Commenting on the siblings’ relationship, Kallir described the way the publicly shy artist would bully his sister: “In the morning he was at her bedside, clock in hand, to wake her. At the count of three she had to be up and ready to pose.”9

Nude Girl with Folded Arms (Gertrude Schiele) (1910, watercolor and black crayon on paper, 19¼″ x 11″ [48.8 x 28 cm]). Albertina, Vienna. Egon also used his power over Gerti to force her company on train rides around the Austro-Hungarian Empire, perks he enjoyed by virtue of his family’s employment by the railroad. In one of their several trips to Trieste, sixteen-year-old Egon checked into his parents’ honeymoon hotel with twelve-year-old Gerti. 10

In connection with that jaunt, Kallir raised the question of incest, defining it vaguely as behavior that “went beyond the realm of what would today be considered permissible, or resulted in any overtly sexual escapades.”11 A four-year age difference and a male’s gender advantage enabled Egon to enjoy a control over something/somebody in his life that had heretofore been unattainable. Whether that included actual sexual contact with Gerti remains unknown, but it’s clear that Egon abused the authority he had over his younger sister for his own gratification. Poor Gerti. One also has to wonder what precious possession she might have lost to the out-of-control father who could destroy his son’s prized drawings and his wife’s major means of financial support.

Pregnant Woman (1910, watercolor and charcoal on paper, 17¾″ x 12¼″ [45.1 x 31.1 cm]). Private collection. Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York. Other sources of models for Schiele included street urchins and prostitutes, and–in exchange for an oil portrait of a gynecologist at a women’s clinic–pregnant women and their babies. Among several of those works on display at the exhibit, Pregnant Woman (1910) stood out for its geometricity and idiosyncratic use of color: the circle of the abdomen contrasts with the right angles of the arms; the green wash of the face and belly complement the red orange of the breasts and arms; and the brown of her stockings relates to that of her hair.

Schiele captured his subject with her arms stretched out to the sides, handless forearms dangling. Her head droops onto her shoulder, her heavy-lidded eyes roll upwards and reveal space under the pupils, suggestive of a trance/hypnotic/drugged state. The artist disappeared the setting, focusing all attention on the exposed woman who might have been premedicated in advance of an examination and now found herself visited by some strange young man with paper and paint.

Nude Girl with Arms Raised (1910, pencil on tan wove paper, 17⅜″ x 12¼″ [44.1 x 31.1 cm]). Private Collection. Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York. Girls willing to model for some change were easy enough for Schiele to come by in lower-class neighborhoods throughout the city. Part of a series depicting a pair of black-haired girls he hired to pose for him, the pencil drawing Nude Girl with Arms Raised (1910) epitomizes the command that Schiele exercised over his line.

In this sketch, the artist confidently traced the contour of his subject’s body and added marks to sparely indicate nipples, navel, facial features and pubis. By drawing extra lines to darken the eyes and pubic hair, Schiele set them off as brackets for the torso. By having the young girl lift her arms, he assured the viewer visual access to her body. Compositionally, Schiele managed to suggest his model’s thighs, bent knees and lower limbs by discontinuing her legs just short of the bottom edge of the page, and picking them up again at her left ankle and foot.

Because he was only twenty, Schiele’s predilection for young girls as models might seem less jarring than had he been a seasoned artist, but it still highlights the disparity in status between male and female, bourgeois and working class. Kallir makes a case for the artist’s being motivated by both his own natural curiosity about sex (he was still developmentally an adolescent) and his desire to overturn conventional mores by placing women’s sexuality on an equal footing with men’s, thus liberating them at least pictorially.