Art Reviews

Print This Post

Sunday, November 14th, 2010 Print This Post

Sunday, November 14th, 2010

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt:

Sculptor of Pain

Many years ago in a mountain town in what is now Germany, a ten-year-old boy’s father dies and within months the child finds himself in an unfamiliar and urban environment after his mother moves the family to Munich to live with her brother. Soon after, the boy becomes an apprentice in his uncle’s sculpture studio. Years later as an accomplished portraitist, he produces over the course of 12 years a series of unusual heads that remain in his studio until after his premature death at age 47.

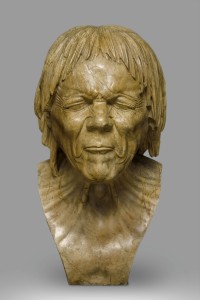

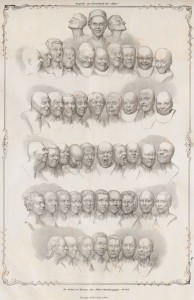

- Matthias Rudolph Toma (1792-1869), Messerschmidt’s “Character Heads” (1839, lithograph on paper), Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

Historical records provide little additional early biographical data on Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, the subject of that story and of an exhibit at the Neue Galerie, beyond those directly relevant to his artistic development. Born in 1736, by age 23 he had secured commissions from the royal family in Vienna, where he had moved six years before to study at the Academy of Fine Arts.

Hints of emotional instability surface by 1770, the year Messerschmidt’s financial success enables him to purchase a house in the suburbs. Coincidentally, that year also sees the death of his patron of 15 years, the artist Martin van Meytens (1695-1770). By 1771, at age 35, the sculptor’s life has unraveled.

Commissions have slowed to a trickle and the support he’s enjoyed as acting professor at the Academy evaporates. In 1774, when the Academy’s professor of sculpture dies, Messerschmidt–long considered his natural successor–finds advancement barred. The professors’ committee seizes this opportunity to free themselves of a man whose “…reason occasionally seemed subject to madness.”1 Further along the decision-making ladder, the State Chancellor reports that the artist is “not suitable for [the position]…because for the past three years he had demonstrated ‘some mental confusion’ and suffered occasionally from an ‘unhealthy imagination.’”2

During this period of time, in an attempt to prevail over his demons, Messerschmidt begins work on what will later be called–for lack of better understanding–“character heads,” sculptures depicting extreme facial expressions. His artistic talent and ability never desert him, as evident in the exquisite 1773-74? portrait of Prince Joseph Wezzel of Liechtenstein.

- Prince Josef Wenzel of Liechtenstein (1773-74?, tin cast), Sammlungen des Fürsten von und zu Liechtenstein, Vaduz-Vienna.

In 1775, Messerschmidt attempts to relocate. He fails to find room at his childhood home, tries Munich for several years, then in August 1777, finds a place to live and work in Bratislava (now part of Slovakia) with his younger brother, also a sculptor. Within three years he has purchased his own home outside the city, where a brief illness thought to be pneumonia, ends his life in 1783.

The Neue Galerie’s exhibition, Franz Xaver Messerschmidt 1736-1783: From Neoclassicism to Expressionism, showcases both the skill and eccentricity of this artist. Greeting the viewer at the entrance to the show, an oval screen mounted behind a drawn picture frame, part of an ornately decorated wall, runs a video showing the “character heads” morphing one into another, looking for all the world like the sculptor posing in front of his mirror.

The first gallery presents work from Messerschmidt’s Early Years in a spacious room with white walls covered with outlines of Baroque paneling and intricate scroll work. Occupying a vitrine in the center of the mostly empty space, six portrait heads dating from as early as 1769, but also as late as 1782, establish the skill with which the sculptor captured images in marble and metal, and perhaps also the soundness of his mind.

Standing on its own in a corner, the portrait of Prince Joseph Wezzel of Liechtenstein, like the uncaged sculptures in later rooms, draws immediate attention by the power of its achievement. Metal becomes flesh and hair, bringing to life one of Messerschmidt’s first patrons.

In the second gallery, the viewer meets the artist transformed. A chorus line of seven heads in a long vitrine kicks off the intriguing subject of Messerschmidt’s Character Heads, his motivation for creating them, and his mental state at the time.

The impossibility of knowing the exact etiology and nature of the sculptor’s breakdown has not deterred the propagation of hypotheses, beginning with Friedrich Nicolai’s account of his 1781 visit to the artist’s studio. In a skeptical and condescending tone, Nicolai made observations and shared what he managed to extract from the reticent Messerschmidt.

He learned that spirits “frightened and plagued [the sculptor] at night,” pursuing him despite his having “lived so chastely.”3 Following a convoluted line of reasoning that Nicola valiantly attempted to record and explain, Messerschmidt arrived at the belief that “the Spirit of Proportion was envious of him because he came so close to perfecting his knowledge of proportions and for this reason caused him those pains [in his belly and thighs].”4

Further, the artist imagined that “if he pinched himself in various parts of his body, especially on his right side amid the ribs, and linked this with a grimace on his face which would have the same Egyptian proportion required in each instance with the pinching of the rib flesh, the height of perfection would be attained” and therefore protect him from the spirits.5

Nicolai came to his own conclusions about what ailed Messerschmidt as did Ernst Kris centuries later in his 1932 book on the sculptor, elements of which appeared in the 1952 English translation of his Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art.6 Each naturally brought to the endeavor his own point of view, not unlike the blind men and the elephant. Nicolai embedded his assessment in the rational thinking of his Age of Enlightenment and Kris wrote in the psychosexual language of Freudian theory.

The “character heads”—the best place to start in any analysis of Messerschmidt—tell their own story, speaking volumes about him. Unfortunately, because no one has yet found a way to date them, they can’t be used to track the evolution of his condition. Nor has anyone had the courage to alter the misleading and sometimes comical names given them after Messerschmidt’s death.

As a group, the “character heads” suggest a person in great distress. Although Messerschmidt referenced his own mirror image, only some approach self portraiture, the rest depict types. Most of the sculptures have eyes shut so firmly that folds and wrinkles accrue around them. The ones with wide open eyes stare blankly at nothing in particular, an effect enhanced by the absence of pupils. A few open their mouths but the majority close them tightly, hiding their lips. By way of explanation, Messerschmidt pointed out to Nicolai that “men must simply pull in the red of the lips entirely because no animal shows it.”7

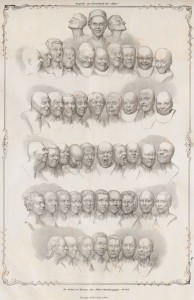

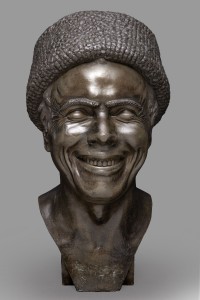

- The Artist as He Imagined Himself Laughing (1777–81, tin cast), private collection, Belgium

Messerschmidt’s suffering suffuses all his “character heads” including The Artist as He Imagined Himself Laughing. Closely resembling its creator, this sculpture presents a man in a lamb’s wool hat with a mouth open wide enough to show the top row of his teeth. As expected in any heartfelt grin, the action of the muscles that pull back the corners of the mouth push up the lower lids to cover the bottom of the eyes.8 That they come almost halfway up the eye belies the expression’s authenticity and provides evidence of the sculptor’s striking the pose for other than representational purposes, perhaps to openly challenge his demons.

![Plate 18, The Difficult Secret [Front] for site](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Plate-18-The-Difficult-Secret-Front-for-site-217x300.jpg) - The Difficult Secret (1771-83, tin cast), private collection, New York.

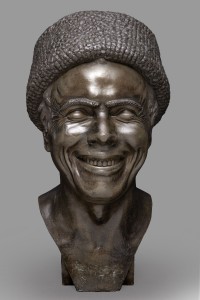

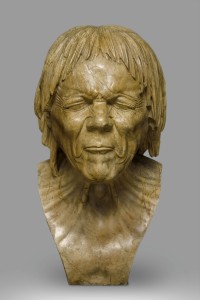

Anything but happy, The Difficult Secret expresses Messerschmidt’s pain in its eyes, where the action of the muscle raising the inner portion of the left brow pulls up the inner corner of the left upper lid.8 The downturned corners of the mouth, usually associated with disgust,9 coupled with the clenched lips, give the impression of grim determination. Each sculpture portrays Messerschmidt’s relentless battle to repel the evil spirits haunting him.

- A Hypocrite and Slanderer (1771-83, metal cast [lead-tin alloy?]), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Possessing one of the sillier names, A Hypocrite and Slanderer departs from the typical upright or slightly lifted head positions by tilting downward, requiring viewers to get on their knees for a complete view, raising the question of Messerschmidt’s own position while creating it. With the head retracting into the chest/body/self, this sculpture poignantly expresses the sculptor’s shame.

Messerschmidt could have unconsciously projected onto imagined evil spirits those impulses and emotions that his psyche found intolerable. Young children who lose a parent often blame themselves for the loss, remembering times when in a fit of frustration at a request denied, they wished their parents dead. For a child, the loss of a parent equates with abandonment and leads to diminished self-worth; after all, parents don’t leave good children. Without help, these children grow up harboring unanswered questions about early parental loss, and doubts about their own role in their parent’s death.

From age 19, Messerschmidt benefited from a relationship with the much older van Meytens, his early patron, perhaps more than just artistically and professionally. The 15-year bond with van Meytens provided an opportunity for the artist to receive care and attention from a father figure but might also have stirred up fears based on unconscious shame, guilt and rage from the long ago death of his father. In addition, the natural competition between student and teacher might have contributed to Messerschmidt’s projection of jealousy onto his demons following the man’s death, a manifestation of his guilt over seeking to best his mentor. Finally, consideration must be given to the possibility that the relationship with van Meytens had a sexual component, which would explain Messerschmidt’s lack of interest in women and his sexual conflicts.

When van Meytens died in 1770, Messerschmidt found himself awash in that little boy’s emotional turmoil. Adults who re-experience child feelings usually fear for their sanity because of the visceral and non-adult-like intensity of them. To preserve his ego, Messerschmidt regrouped by blaming his reactions on jealous demons who pursued him. Paranoid feelings can indicate projected guilt. When the paranoia overflowed into his work situation, the Academy had to get rid of him. Once again he found himself abandoned.

- Just Rescued from Drowning (1771-83, alabaster), private collection, Belgium.

- The Vexed Man (1771-83, alabaster), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

In two carved alabaster sculptures, Just Rescued from Drowning and The Vexed Man, Messerschmidt demonstrates his expert handling of the soft stone, incising impossible wrinkles to suggest aged skin and to emphasize the expression. With pursed lips, scrunched up noses, shut eyes and heads pitched forward, these old men anticipate imminent contact with something distinctly unpleasant. They brace for it and at the same time seem resigned to its inevitability.

- The Yawner (1771–81, tin cast), Szépművészeti Múzeum (Museum of Fine Arts), Budapest.

At first glance, The Yawner seems to be screaming, but a mouth that opens by lowering the chin into the chest impedes the flow of air in and out of the lungs, opposite of the maximum exhalation required for a scream. As for the work’s title, Darwin had this to say about yawning: “[It] commences with a deep inspiration, followed by a long and forcible expiration,”10 not possible under these circumstances. The vulnerability of the open mouth contrasts with the avoidance of the retracted tongue, squinting eyes, and nose wrinkled in disgust, indicating ambivalence–or more painfully, conflict–about the situation.

- Quiet Peaceful Sleep (1771-83, tin cast), Szépművészeti Múzeum (Museum of Fine Arts), Budapest.

The title bestowed by the anonymous author who originally named the “character heads” comes closest to accuracy in Quiet Peaceful Sleep. Here Messerschmidt has captured in a face devoid of the usual abundance of wrinkles an expression of peaceful resignation. Gently lowered upper lids close the eyes under a minimally knitted brow. The nose sits neutrally over a mouth that betrays some tension in its thinned upper lip, which rests on a full lower one. The expression brings to mind the state of the suicide shortly before an attempt, when despair has lifted enough to liberate energy for action; a calm descends on the victim who looks forward to final release/relief from pain.

For a full comprehension of Messerschmidt’s struggles, notice must be paid to the sculptures with bands across their mouths. If the tightly pressed and retracted lips in the rest of the heads fail to impress with their need to keep something in (or out), then slapping a strip across the mouth surely clarifies that intention.

Messerschmidt must have feared the power of his mouth to give voice to the taboo feelings he carried and perhaps also to divulge the true nature of his relationship with his early patron. Wrestling against that force, he left behind for posterity to ponder, beautifully crafted alabaster and metal portraits that continue to keep his secrets.

______________________________

1 Maria Pötzl-Malikova in Franz Xaver Messserschmidt 1736–1783, 21.

2 Ibid.

3 Frederich Nicolai, “Description of a Journey through Germany and Switzerland in the Year 1781, in Franz Xaver Messserschmidt 1736–1783, 208.

4 Ibid, 209.

5 Ibid.

6 Ernst Kris, Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art, 1971, 128.

7 Op cit.

8 Paul Ekman and Wallace V. Friesen, Unmasking the Face: A Guide to Recognizing Emotions from Facial Expressions, 1975, 104–5.

9 Ibid, 117–119.

10 Charles Darwin, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, [1872], 1989. 165.

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt 1736-1783:

from Neoclassicism to Expressionism

Neue Galerie

1048 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10028

(212)628-6200

Catalog available.

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Tuesday, October 5th, 2010 Print This Post

Tuesday, October 5th, 2010

Gottfried Helnwein:

“I Was a Child”

Wandering through the Friedman Benda gallery in Chelsea, the viewer encounters large format, hyper-realistic paintings of children with expressions ranging from inquisitive to apprehensive and sad. Not unknown in the United States, the creator of these works, Austrian expatriate Gottfried Helnwein, currently enjoys an opportunity to introduce his subjects to a broader audience with his first full-scale exhibition in New York.

- The Murmur of the Innocents 3 (2009, oil and acrylic, 87″ x 130″)

The painting that greets visitors, The Murmur of the Innocents 3 (2009, oil and acrylic, 87″ x 130″), in its relative innocent portrayal of a young blond girl in a camisole, barely hints at the distressing depictions that follow.

- The Murmur of the Innocents 16 (2010, oil and acrylic, 86″ x 130″)

Several of the other works in The Murmur of the Innocents series contain images of a girl in a military-like, navy blue jacket with epaulets and gold braiding on the cuffs, (numbers 16, 17, 18, 19 and 20). Three of these are closeups of the girl’s face, one has her left hand covering half her face, perhaps wiping a tear from her eye, and the first shows her from the shoulders up, lying near a pool of red with bloody nose and blood-soaked hair.

- The Murmur of the Innocents 20 (2010, oil and acrylic, 71″ x 47″)

Lest there be any doubt that these images speak about the impact of violence on children, in number 5, the young blond girl from the first painting, now dressed in a long white undershirt, holds a machine gun pointing to the right of the viewer and looks sideways at a cool green, toy manifestation of a cartoon character, reminiscent of Roo from Winnie the Pooh, who stands with hands on hips and stares back.

- Untitled (Disasters of War 24) (2010, oil and acrylic, 195″ x 243″)

In another piece, Untitled (Disasters of War 24) (2010, oil and acrylic, 195″ x 243″), a child with a gauze bandage wrapped around forehead and eyes, wears a white lab coat with epaulets and decorative cuffs, and points a large pistol at an icy blue girl doll, passing along the legacy of violence.

How does an artist come to such subject matter? Helnwein, born in 1948 in Austria amid the devastation that was Vienna at the time, grew up in a world that offered abundant evidence of humans’ capacity for cruelty. In an interview with Peter Frank, posted on the gallery’s website, he had this to say:

Maybe it’s a defect, yet ever since my earliest childhood I have seen violence all around me, as well as the effect of violence: fear. I absorbed any piece of information I could get hold of on persecution and torture like the Holocaust, the Vietnam War, tyrannical regimes such as that of Pinochet’s Chile, the Inquisition…and finally, the general mistreatment of children.

The obsession with inflicting maximum pain on others, in particular on the defenseless, that runs throughout human history has always been a mystery to me. The creativity that people develop in committing such atrocities is startling.

How can someone show anything but love and admiration to children? I have seen pictures taken by forensic doctors of children who had been tortured to death, often by their own parents, images that will not let you sleep well for awhile.

That was the reason I began to paint: aesthetics were not my primary motivation.

By the age of 18 I finally realized that art was probably the only possible way of defending myself against the impertinences of society. For me art was a weapon with which I could finally strike back.

Less a defect than a search for meaning, Helnwein’s acute awareness of ambient violence stems from his own childhood immersion in the visual evidence of its ubiquitous nature. His artwork forces viewers to confront the same mysteries of human nature’s dark side that have long troubled him.

“I Was a Child”

Gottfried Helnwein

Friedman Benda

515 West 26th Street

New York, NY 10001

(212)239-8700

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Sunday, September 26th, 2010 Print This Post

Sunday, September 26th, 2010

Drawing Against the Grain:

Gerhard Richter on Paper

“I could do that,” a girl of about 11 declared to her father as she glanced at Drawing III, one of four large-format drawings that covered the far wall during the exhibit, Gerhard Richter “Lines which [sic] do not exist” at The Drawing Center. “That’s where you’re wrong,” he countered, though never explaining how a collection of graphite lines, smudges, shadings and erasures, representing nothing recognizable, qualified as accomplished art.

Of this group (all 2005, graphite on paper, 59½” x 40⅜”), Drawing II garnered more interest from some viewers, one of whom when asked expressed appreciation for the variety of lines, contrast and use of erasures. The best of the four, the drawing achieved, in two central areas of smudging and erasure, effects similar to those found in many of the artist’s abstract paintings from 2000.

Arranged on the walls around the rest of this nonprofit exhibition space, smaller drawings and occasional watercolors rested on individually constructed, lipped, wooden shelves painted white. In an arrangement governed by no particular ideology, the display reflected the artist’s well-known approach to art making. Never one to run with the crowd, Gerhard Richter has always found his own way in his explorations of the infinite possibilities of paint and other media. The idea for the physical presentation and absence of order, according to Brett Littman (The Drawing Center director), belongs to the current venue; though Richter approved the show, he did not hang it like he has done elsewhere.¹

- Gebirge/Mountains (1968, graphite on paper, 19¼” x 21½”), permanent loan from a German private collection, courtesy Kunsthalle Emden.

This show, featuring less well-known aspects of Richter’s practice, displayed over 50 mostly small format works on paper that included wanderings with graphite pencils, sticks and perhaps powder–with minor assistance from an electric drill–and a few ink and watercolor pieces.

The title refers to a statement by the artist on the difference between his paintings and drawings in their closeness to representation. Because of the use of color in his paintings, even abstract ones, they come closer to reality, he believes, in a way that his drawings don’t.² Richter uses the traditionally held belief that lines don’t exist in nature to position his drawings further from the real world than his paintings.

Because Richter was born in Germany in 1932, his personal history coincides with that country’s descent into the darkness of first the Nazi era and World War II, then the partitioning of Germany and Berlin into the Communist east and capitalist west. Raised by a mother who spoke contemptuously to her son of her absent husband–drafted, then captured during the war–Richter confirmed not so long ago what his mother had always intimated, that the man who raised him was not his birth father.³

Not surprisingly, Richter developed a deep and abiding suspicion of any ideology– political, intellectual or artistic, and an allegiance to none. In striving in all his endeavors to steer clear of any identifiable attachments, he has created a unique and varied body of work.

Explored in the thoughtful catalog written by the curator, Gavin Delahunty, Richter’s relationship to drawing begins with a certain skepticism about its potential for flaunting virtuosity and his lack of faith in his own facility for it.4 A review of the exhibit’s offerings belies that self assessment and lends credence to Littman’s suggestion that the artist is “self negating.”5 Here Richter has plenty of company; artists criticize their work far more harshly than others.

Far from reflecting lack of skill, Richter’s works on paper suggest a child playing with new toys, though for this artist the novelty never seems to wear off. From the first to the last, each piece illustrates an experiment in the application of graphite (and sometimes watercolor and ink) in Richter’s determined search for the beautiful image.

- 22.4.1990 (1990, graphite on paper, 8¼” x 11-11/16″), courtesy Kunsthalle Emden.

The first hint of that exploration appears in a drawing at the very beginning of the exhibit. In 22.4.1990 (8¼” x 11-11/16″), the viewer encounters delicately applied dabs of graphite of differing weights progressing from darker to lighter as they march across the page from left to right, interrupted along the way by randomly spaced vertical erasures that lend the image depth.

Taking that inquiry further, in 1.6.1999 (8¼” x 11-11/16″) Richter adds scribbled graphite lines of assorted weights over a lightly shaded horizontal swatch covering a bit more than half of the drawing’s lower portion and the considerably darker one above it. Using an eraser, he creates two shining orbs in the dark, two smaller ones in the light, and horizontal and vertical lines–the sum total of which suggests a landscape on another world.

- 27.4.1999 (5) (1999, graphite on paper, 8¼” x 11-7/8″), private collection.

In discussing abstract art, Richter has described it as “narratives of nothingness” that prompt viewers to search for recognizable patterns.6 But he has also acknowledged the importance of landscape throughout his ouevre7, which invites the question: How many of these drawings hide attempts to capture the essence of reality beneath abstract imagery?

- 20.9.1985 (1985, graphite on paper, 8¼ x 11-11/16″), courtesy Kunsthalle Emden.

The only clearly representational image in the show, 20.9.1985 (8¼” x 11-11/16″, graphite on paper) highlights Richter’s exquisitely sensitive line. In it, a bare-breasted woman reclines on her back with her left arm extended toward the edge of the picture plane, bending at the elbow to run parallel to it and ending with the hand holding open a book. Varying line weights and delicate hatch marks combine to form a landscape that ends with several horizontal lines above the woman’s contour. Cutting off the head with the left edge of the paper enhances the perception that the image represents more than a woman lying on the beach. It hints at the inherently abstract nature of reality.

The delicacy of Richter’s application of graphite on smooth and toothed paper, coupled with the experimental nature of his mark making, lends his drawings lightness of being. While some fall short, many come close to that beautiful abstract reality Richter courageously pursues.

¹ Brief interview with Brett Littman, September 11, 2010.

² Gavin Delahunty, Gerhard Richter “Lines which do not exist,” 2010, 20.

³ Michael Kimmelman, “An Artist Beyond Isms,” The New York Times Magazine, January 27, 2002, 21.

4 Interview by Robert Storr in “Gerhard Richter: The Day is Long,” Art in America, January 2002, 72.

5 Littman, 2010.

6 Kimmelman, 24.

7 Dietmar Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, 2009, 269-277.

__________________________________

Gerhard Richter “Lines which do not exist”

The Drawing Center

35 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10013

(212)966-2976

Catalog available.

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Wednesday, August 11th, 2010 Print This Post

Wednesday, August 11th, 2010

Heat Waves in a Swamp

on a Steamy NYC Day

Charles Burchfield, An April Mood, 1946–55. Watercolor and charcoal on joined paper, 40 x 54 in. (101.6 x 137.2 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art. Purchase, with partial funds from Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence A. Fleischman. With temperatures outside nearing 100°F and humidity to match, the chilly galleries of the Whitney Museum of American Art seemed like the perfect place to spend the afternoon. Even more inviting were the rooms filled with the doodles, drawings, designs and watercolor paintings by the master craftsman Charles Burchfield.

Exiting the stairwell (or elevator) into the introductory gallery, one was greeted by Autumnal Fantasy, a large watercolor (39″ x 54″) completed in 1916 and augmented in 1944. In this landscape, the warm yellows and oranges of the leaves falling on the water and carpeting the ground contrast with the cool blacks and blues of the tree trunks, water, and the two white-breasted nuthatches that frame the scene. Light from an almost-white sun touches everything in the picture. Reverberating boomerang-like black shapes picture the songs of birds, both seen and hidden.

Odd, though, that this first painting was not the eponymous Heat Waves in a Swamp. In the catalog (p. 9) Robert Gober, an artist in his own right and curator of the show, explains that he chose the title because he felt it best represented Burchfield’s interest in nature and particular fondness for swamps. The watercolor, known only by its listing in several earlier catalogs, remains lost, but the many other, chronologically arranged, pictures offered plenty of insight into Burchfield’s process.

Lest anyone misunderstand this artist’s intentions, Charles Ephraim Burchfield left behind 72 volumes of journals (some of which were displayed in a vitrine in the last room of the show), starting at age 16 and continuing until his death in 1967. Containing thoughts about all aspects of his life and work, they provide unusual access to his interior life.

Born in 1893 in Ashtabula Harbor, Ohio, Burchfield had this to say about his childhood: “Father died when I was four and a half years old, leaving the family destitute. Mother moved with her ‘brood’ (four boys and two girls–I was the fifth child) to Salem, Ohio, her home-town…” (p. 21) As a left-handed child, living in poverty in a single-parent home, the boy overcame great hardship to grow into the mature artist he eventually became.

Burchfield encapsulated his recollections of that time in the watercolor-and-graphite Childhood’s Garden, dated August 22, 1917, for which a preparatory conté crayon drawing exists (Nostalgia) from the same year (p. 28, 29). In the painting, a green figure, suggestive of both phantom and tree, occupies the space beneath an angled roof that in the drawing contains a haloed woman in a doorway, silhouetted against a dark interior. In each image, a lush garden blooming with flowers threatens to swamp the house; in the painting, menacing trees press in against it. Burchfield described the artwork as “based on childhood memories of our garden at Salem, O.” (p. 28)

Among the many flowers in that garden, six stand out for their sad faces, suggesting the unhappiness of fatherless children. One, probably representing Burchfield, is grouped not with his five siblings but with an orange flower, perhaps their mother. Isolated beyond a growth of yellow and white vegetation, another orange flower hints at the impossibility of reunion with their father, as does the ghostlike phantom/tree that blocks retreat into the home.

The death of Burchfield’s father and the space left empty by it reappears in various forms throughout much of the artist’s work. Images of frightening weather depicted in several 1918 works like The Night Wind, The East Wind and Rainy Night capture the terrors he experienced as a child. In another watercolor of that year, White Violets and Abandoned Coal Mine, the entrance to a mine occupies the center of the painting while in the foreground grow three white violets in various stages of bloom. The choice of a flower at times associated with death and resurrection, coupled with the big black hole of the abandoned mine, leads the viewer directly into the depths of Burchfield’s unconscious.

Along similar lines, in a collection he called Conventions for Abstract Thoughts (not to be confused with the art form of the same name, he cautioned), the 22-year-old artist devised an iconography of dark moods that included: “Fear, Morbidness (Evil), Melancholy/Meditation/Memory of pleasant things that are gone forever, Dangerous Brooding, Imbecility (opposite), Fascination of evil, Insanity, Aimless Abstraction (Hypnotic Intensity) and (untitled) Fear 1″ (p. 22), most of which were on display. A great addition would have been a crib sheet containing images of all of them to help viewers decipher Burchfield’s visual code.

Wandering from one room to another at the Whitney, one could appreciate the ebb and flow of Burchfield’s creative process. After what he called his “golden year” of 1917, he did a stint in the Army where he ended up creating camouflage designs, then moved to Buffalo where he worked at a wallpaper company. Samples of both kinds of design were on display although an entire gallery papered in orange and yellow sunflowers amid blue and yellow leaves against a grey-green tangle of stems distracted from the other artworks hanging there and produced reflections on their glass.

Charles Burchfield, Black Iron, 1935. Watercolor on paper, 281∕8 x 40 in. (71.1 x 101.6 cm). Private collection. Continuing to pursue his own art even as he worked to support his wife and five children, Burchfield eventually attracted gallery representation and quit his day job. During the years that followed, he painted realistic watercolors of trains, bridges, industrial scenes, townscapes, and woods and gardens, work that sold well and brought him widening acclaim.

When he turned 50, Burchfield began to yearn for the freedom he felt in his 20s when he produced his most daring work. Revisiting, quite literally, some of those earlier pieces, he carefully attached paper to accommodate expansions on the original ideas. The preparatory sketches included in the exhibit, as well as the paintings themselves, demonstrate the artist’s uncanny ability to tap into the adolescent energy still active in one’s 20s, when the brain has not yet finished the work it began in its teens.

Charles Burchfield, Dawn of Spring, ca. 1960s. Watercolor, charcoal, and white chalk on joined paper mounted on board, 52 x 591∕2 in. (132.1 x 135.3 cm). DC Moore Gallery, New York. Able to pick up where he had left off in his youth, Burchfield spent the rest of his life producing ever more fanciful celebrations of nature. The last gallery of the show contained an array of large, colorful watercolors, most of which incorporated earlier works. More than a few viewers could be found playing the game of find the joins of the add-ons.

One stunning transformation occurs in Song of the Telegraph (1917-52). To a considerably smaller painting of telegraph poles receding into the distance, Burchfield affixed paper on all sides. At the base, a new foreground of greenery now supports another vibrating pole on the right and the appearance on the left of a corralled stand of trees haunted by dark, ghostlike figures in front of which, perched on a prominent fencepost, sings an eastern bluebird surrounded by a halo of yellow and white light. The broader expanse of sky hosts a flock of unidentifiable winged black creatures heading left, into the past, backed by a huge grey-winged cloud shape, also facing in that direction, in contrast to the blue and orange bird that faces right, toward the future.

Charles Burchfield, Glory of Spring (Radiant Spring), 1950. Watercolor on paper, 401∕8 x 293∕4 in. (101.6 x 73.7 cm). Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Corning Clark, 1959. Although dark patches still appear in Burchfield’s late paintings, as evident in the rain-drenched Night of the Equinox (1917-55), that he found his way to the bright and colorful creations of his last decades speaks to the power of art and nature as transformative forces in one person’s life. The watercolors he left behind resonate with the exuberance one imagines he felt when setting up his image-making gear in his beloved swamps, surrounded by the sounds of birds and other calls of nature.

Heat Waves in a Swamp:

The Paintings of Charles Burchfield

Whitney Museum of American Art

945 Madison Avenue (at 75th Street)

New York, NY 10021

(212) 570-3600

All page numbers referenced are from the catalog:

Heat Waves in a Swamp:

The Paintings of Charles Burchfield

Cynthia Burlingham and Robert Gober, editors

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Sunday, July 4th, 2010 Print This Post

Sunday, July 4th, 2010

Painted Drawings by Dorothea Tanning & Leon Golub

Situated in the Soho section of Manhattan, The Drawing Center with its annex, The Drawing Room, exists to promote drawing as an artistic practice in its own right. Since 1977, when this nonprofit exhibition space was established to foster emerging and under-recognized artists, it has mounted shows of historical, contemporary and innovative work. Designed to demonstrate the important place of this modality in the art of many cultures, many genres and many eras, The Drawing Center has brought a much needed emphasis to drawing as the foundation of all art.

The notion of what constitutes a drawing has broadened considerably since the first prehistoric tracings of hands on cave walls millennia ago. During the Renaissance, Michelangelo said of this art form,

“Let this be plain to all: design (disegno), or as it is called by another name, drawing (tratto), constitutes the fountain-head and substance of painting and sculpture and architecture and every other kind of painting and is the root of all sciences.” (1)

Times change and many of the drawings exhibited over the years by The Drawing Center might have left the Old Master pulling at his beard.

The drawings of Dorothea Tanning’s Early Designs for the Stage on view in The Drawing Room consist of watercolor or gouache and ink on paper while across the street at The Drawing Center, the drawings in Leon Golub: Live & Die Like a Lion? are mostly oil stick and ink on vellum or Bristol with the occasional paper and acrylic.

All these paintings, although works of art in their own right, were designed for specific purposes. In the case of Tanning’s, they provided instructions for creating costumes and sets for three ballets. For Golub, they expressed ideas that, had he the time and the strength, would have found their way into his usually expansive paintings.

The 99-year-old Dorothea Tanning (b. 1910), the oldest living surrealist, met the choreographer George Balanchine in 1945 at a party hosted by New York art dealer Julien Levy. Soon after, they began collaborating on producing the ballet Night Shadow (using music arranged by Vittorio Rietti based on operas by Vincenzo Bellini) in which the Poet becomes enamored of the Coquette at a masquerade ball, meets the Somnambulist (sleep walker), ends up murdered by the Host at the behest of the jealous Coquette and gets spirited away by the Somnambulist.

The otherworldly quality of La Sonnambula (the name by which it has been known since its 1960 staging) and of the other two ballets for which Tanning also designed sets and costumes, Bayou and The Witch, provided fertile ground for the artist’s surrealistic imagination. The fantastic characters depicted appear to have stepped right out of Tanning’s paintings though their rendering suggests images from children’s picture books. Gracefully executed, they both delight and intrigue.

With some of the same mystery inherent in Tanning’s creations, in works he produced during the last five years of his life, Leon Golub (1922-2004) stared down his own mortality. At 72, no longer able to summon the physical effort required to execute the large paintings he developed with repeated scraping and repainting, Golub returned to his roots as a draftsman. After studying drawing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the late 1940s, he had spent the next two decades producing large, graphically based works. It wasn’t until the 1970s and 1980s that he shifted his energies toward painting.

In an interview that took place five months before Golub’s death, the artist had this to say about drawing:

“There’s something about a big painting that says, ‘Let’s be serious, this is a big item!’ Just by scale and ‘cosmic’ intentionality!…A small drawing says, ‘You don’t have to be so tight! OK? If you flub it, so what? The wastebasket is under the table!’” (2)

Considering how harshly most artists criticize their own work, Golub’s wastebasket must have been a treasure trove of discards. Nonetheless, 440 eight by tens did survive, about 60 of which were on display in the huge square gallery of The Drawing Center, punctuated by two centrally located vitrines containing, in one, the contents of a folder of photographs, ideas for paintings, and in the other, oil stick sketches of backgrounds for drawings.

Perhaps the exhibit’s title, Live & Die Like a Lion?, taken from the picture (2002) of the same name, was chosen because FUCK DEATH (1999), although the earliest piece in the show and therefore introductory to the rest, might present problems for the publicity department. Golub was never one to “go gentle into that dark night,” raging as he always did against the abuse of power. His late work continued that tradition, though this time he was raging “…against the dying of the light.”

Aging artists down through the centuries have tended to loosen up in order to speed up their artistic production, and have altered styles and mediums to accommodate their disabilities. Think Monet’s failing eyesight and his disintegrating form in his late years, Chardin’s late self portraits in pastel, and the elderly Titian’s expressionistic brush strokes. So many ideas, so little time.

Golub made good use of his remaining years, confronting the specter of death with images of old lions like the one holding a sign that says Getting Old Sucks (2000), of skeletons like the purple skull of FUCK DEATH, of resistance to enslavement epitomized by the man struggling against his bonds in NO ESCAPE NOW (2002) and the man with bared, white teeth in I DO NOT BEND BENEATH THE YOKE (2002) whose bald head lends it the air of self portraiture. Golub’s many depictions of erotica–nudes, satyrs, and couples copulating–brought to mind Picasso’s late etchings of the Minotaur and his model: the last flickering of a dimming libido.

With a palette of mostly uncut colors–red, blue, turquoise, green, orange–and occasional black, grey and brown, Golub’s “drawings” contain the words of their titles, perhaps in an attempt to render unambiguous his intentions, using all caps when he felt compelled to shout.

Older artists can be expected to incorporate in their work themes related to aging and death simply by virtue of their developmental stage. The tandem Tanning exhibit flashed back to her younger years. A more satisfying coupling with the Golub show would have included her latest, or last, drawings accompanied by her most recent writing; she has in her advanced years given herself over to her other great love, writing. For highly creative people like these two, “[o]ld age should burn and rage at close of day.”

______________________

1 Stephanie Buck, editor, Michelangelo’s Dream, (London: The Courtauld Gallery, 2010), p. 105.

2 “Leon Golub with Douglas Dreishpoon,” Art in America (April 2010), p. 111.

Dorothea Tanning’s Early Designs for the Stage

Leon Golub: Live & Die Like a Lion?

The Drawing Center

35 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10013

(212)966-2976

Catalog available for each exhibit.

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Sunday, June 20th, 2010 Print This Post

Sunday, June 20th, 2010

Between Two Wars: The Masked Truths of Otto Dix

Following the music emanating from a nearby gallery brings one to a small room lined with etchings from two of Otto Dix’s print series. An award-winning dancer, Dix might have been amused by the selection of popular German tunes from the 30s and 40s that played continuously while viewers took in the 10 prints of The Circus and the five of Death and Resurrection.

The experience of contemplating subjects like Suicide, Sex Murder and Dead Soldier while feeling the urge to break into a Charleston reflects perfectly the times in which the artist lived. An artilleryman in World War I who spent three years in the trenches, the artist kept what sanity he could by drawing whenever possible.

After returning to Dresden, Dix pursued recognition for his art while at the same time enjoying the temptations of the Weimar years in Germany, seeking out “revue theaters, film palaces, and circus arenas, the red-light district and the bohemian cafés.” (p. 165) Everything he witnessed found its way into his art, where he exposed the dark side of the glitter.

The Neue Galerie, along with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, has organized a fine review of major works produced by the artist between 1919 and 1939 that includes the 50 etchings of War (Der Krieg), the above-mentioned Death and Resurrection and The Circus, an assortment of paintings in tempera, oil and watercolor, and a number of drawings.

Dix’s oeuvre suggests an unhappy man, one forever scarred by the revelations of trench warfare, which he captured in a disturbing, now lost, work, Trench (Der Schützengraben). A large painting (89⅜” x 98⅜”) that he began working on in 1920, not long after he returned to Dresden from military service, and completed in 1923, it depicts in gory detail the death and dismemberment of both soldiers and landscape. The black and white photograph that appears in the catalog (p. 64) barely hints at the power the life size images, particularly the partially shredded corpse carried aloft on fragments of steel beams, must have wielded in full color.

At least of equal impact are the war drawings and etchings displayed in a dimly lit gallery on the lower floor of the exhibit, tucked away in a corner that requires some sleuthing to discover. Undoubtedly an accidental addition, the large dead fly that stuck to the wall between the second and third images seemed remarkably appropriate, as though attracted by the rotting body parts depicted in some scenes.

One is tempted to categorize the prints of War as either studio elaborations of onsite drawings or riffs and/or exaggerations from the same sources. Transporting the Wounded in Houthustler Forest, illustrating two weary looking soldiers, each walking with the aid of a cane, carrying a man in an improvised sling of coat and log, could have been sketched onsite and later developed more fully with shading.

On the other hand, Mealtime in the Trench (Loretto Heights) begs to be interpreted as a compilation of two different sketches, one of a muddy and bedraggled soldier eating canned rations and another of a disarticulated skeleton strewn across an incline. Likewise, The Skull, with worms crawling in and out of the ocular orbits, nose cavity, mouth, and hole in the parietal (top) bone, must surely be more conceptual than actual. And yet, Dix may very well have seen heads that had reached just such a state of decomposition. Such is the terrible truth of battle.

After the war, in the cities of Germany, wounded veterans sold matches and begged on the street, prostitutes of all ages paraded their wares, and the upper classes ate, drank and danced in their restaurants and clubs. Inflation was rampant and poverty widespread. Somehow Dix managed to assimilate all of this into his drawings, prints and paintings.

Excelling at portraiture, accepting commissions only from figures that interested him, displeasing many a sitter, Dix also featured prostitutes in many of his works. While some of his subjects’ faces suggest likenesses, others resemble masks.

In two of the many female nudes exhibited, the bodies are described with realistic skin tones while their faces are portrayed as add-ons affixed to their heads and painted in a whitish tone. The subject of Reclining Woman on Leopard Skin (1927, oil on wood) appears to be holding a mask in front of her face instead of supporting her head on her hand. The woman in Seated Female Nude with Red Hair and Stockings in Front of Pink Cloth (1930, mixed media on wood) seems to grasp her mask by its forehead and affix it to her face.

In Still Life with Widow’s Veil (1925, tempera on wood), Dix depicts a (death?) mask hanging from a nail high on a wall over a still life of a glass pitcher of water containing two long-stemmed black flowers sitting on an unusually active white cloth covering a table in front of a pole supporting a section of thoracic spine, with attached ribs, draped with a veil.

Masks have traditionally been used as symbols of death, as in Michelangelo’s sculpture of Night in the Medici tombs in San Lorenzo, Florence. Associated with theater, masks hide one’s true visage and suggest a false one. As such, they represent dissembling, deception and duplicity.

The people in the circles Dix aspired to and ultimately joined acted oblivious to the suffering around them. The artist, with his terrible knowledge of combat, could not be expected to easily make peace with these disparities.

In his 1927-28 triptych, Metropolis (portions of which were displayed on screens in the stairwell), Dix highlighted the dissonance he must have experienced by juxtaposing the reality of maimed veterans begging on the street (side images) with the glamor of upper class revelers in a nightclub setting (center).

With the rise of the Third Reich and its confiscation of “degenerate art,” in 1933 Dix had to flee from Berlin (where he’d been living since 1925) for the relative safety of a friend’s country estate. There, among other works, he produced landscapes that stand out for both their subject matter and beauty.

In the best of those exhibited, the Elbsandstein Mountains (Schrammsteine) rise up in the background and meet the clouds in masterly rendered atmospheric perspective (1938, oil and tempera on board). Several houses occupy the middle distance, farmland recedes toward the mountains and also climbs up toward the foreground, where a meticulously rendered leafy tree on the right frames the scene.

Removed from the clamourous environment of Berlin, Dix produced carefully observed, tightly rendered works like these and others. Years later, in an attempt to recapture his earlier, freer style, he would repudiate these and other traditionally painted works with the comment, “I have been painting much too much with the tip of the brush for the last twenty years.” (p. 241)

Dix would continue to live in the country until his death from a second stroke at the age of 77 in 1969. He would work both there and in the studio he maintained in Dresden.

Otto Dix

The Neue Galerie

1048 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10028

(212)628-8824

All page numbers referenced are from the catalog:

Otto Dix

Olaf Peters, editor.

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Sunday, May 30th, 2010 Print This Post

Sunday, May 30th, 2010

Shades of Loss: Expressions of Grief in the Printmaking of Käthe Kollwitz

In 1938 at the age of 71, Käthe Kollwitz drew another one of the over one hundred self-portraits she would create in her lifetime. Self-Portrait in Profile, Facing Right depicts an aged woman in a dark shawl with her hair tucked under a white, skull-fitting cap. With the lid covering half her eye and her mouth turned down at the corner, she looks weary as she faces an uncertain future.

A resident of Berlin, by that time Kollwitz had witnessed the rise of Hitler’s National Socialist party (1933); and by 1938, the persecution of the Jews and others was a distressing reality. That year, for two days in November all across Germany, Jewish businesses, homes and synagogues had been attacked, an episode that came to be known as Kristallnacht (the night of broken glass). The march to yet another war was well underway.

Born in Königsberg, Germany on July 8, 1867, Kollwitz witnessed her one-year-old brother succumb to meningitis just as her mother, Katharina Schmidt, had seen her first-born do soon after birth; another son had also died before Kollwitz was born.

In a 1919 lightly-sketched lithograph, Killed in Action, a woman covers her face with her hands save for the mouth, which opens in a scream, while her three children look up at her, wide-eyed with fear at their mother’s grief; two of them tug at her skirt, the other holds his hands up near his face. The drawing, one among many dealing with the personal toll of war, followed five years after Kollwitz lost her younger son Peter at the beginning of World War I.

Killed in Action might also reflect Kollwitz’s childhood experience of her mother’s unexpressed grief. Katharina, who stoically suppressed her tears, focused instead on the tasks of raising four children (of which Kollwitz was the third), remaining out of reach for Käthe who ached to comfort her. Unable to soothe her mother’s pain, though exquisitely receptive to it, Käthe carried it, expressing it in hours-long crying jags, feeling it in recurring stomach aches, and replaying it in recurrent nightmares throughout her childhood. The three children startled by their mother’s wail in the lithograph could be Käthe and her two older siblings.

One can see these prints at The Galerie St. Etienne along with many others in Käthe Kollwitz: A Portrait of the Artist, a loan exhibition celebrating both the 25th anniversary of the Käthe Kollwitz Museum in Cologne and the 70th anniversary of the affiliation of Hildegard Bachert (director, author and expert on Kollwitz) with the gallery.

The show included not just self-portraits but also images depicting motherhood, loss and death. The plight of workers and their struggle, another prominent theme especially in Kollwitz’s early work, was largely absent. The prints and drawings selected lend credence to the observation that from very early on the artist struggled against a tide of grief relieved only by the birth of each of her two sons and the joy that tending infants gave her.

On the subject of motherhood, in the lithograph Mother, Pressing Infant to Her Face (First Version), Kollwitz accentuates the closeness of mother and child by juxtaposing their profiles so that the curve of one nose fits into the curve of the other, foreheads and lips press together, and the visible eye of each completes the whole in an eloquent representation of their symbiotic relationship.

Attachment portends loss through separation or death. When war broke out in 1914, 18-year-old Peter enlisted, caught up in the patriotism that swept through Germany at the time. Kollwitz, deeply troubled by his departure, ruminated about how mothers could so readily offer up their progeny. In a diary entry dated August 27, 1914 (two months before Peter was killed), she wrote, “Where do all the women who have watched so carefully over the lives of their beloved ones get the heroism to send them to face the cannon?”

Her 1942 lithograph Seeds for Sowing Must Not be Ground admonishes all to refrain from sacrificing their children, the seeds for future harvests. In a triangular composition, a mother shelters her three children within the tent of her body and enfolds them in her arms, attempting to shield them, and perhaps herself, against the inevitable time when they outgrow her ability to keep them safe. In September 1942, Kollwitz lost her grandson Peter to yet another war.

Very early on, Kollwitz had acquired the terrible knowledge that parents sometimes outlive their children. She had witnessed her mother lose a son and later had lost her own son and grandson in two world wars. She represented in many works the agony a mother feels over the death of a child but perhaps in none so poignantly as in the 1903 etching and drypoint Woman with Dead Child.

One of many such images, this one captures best the desperate grief of a mother who sits cross legged and clutches her dead child, her nose pressed against his neck as his lifeless head hangs down beyond her arms, as if willing her spirit into him, to give of her life so he can live.

There are images, too, of grieving parents. After losing Peter in 1914, Kollwitz devoted herself to creating a memorial that became two monumental sculptures finally erected in 1932 at the gates of a military cemetery in Belgium. The 1921-22 woodcut The Parents, Third Version shows an early idea for a single monument with both parents on their knees, facing each other, forming a single, sculptural unit. The father rests his arm on the mother’s bent back and covers his head with his hand. The mother buries her head in the crook of the father’s arm. Their faces are hidden. Their grief is palpable.

As she aged, Kollwitz began to look toward death for relief from her suffering. Around the time she turned 70, she produced the self-portrait Call of Death. In this 1937 lithograph, the artist looks at a skeletal hand that enters the picture from the right and touches her shoulder. The orbits of her eyes are in deep shadow and she looks very tired.

Käthe Kollwitz lived another ten years, outliving her husband by five and dying several weeks before the armistice ended World War II. Her work remains a testament to the power of art to triumph over even the most profound despair for surely it was Kollwitz’s passion for art that kept her productive for so many years.

Käthe Kollwitz: A Portrait of the Artist

Galerie St. Etienne

24 West 57th Street

New York, NY 10019

(212)245-6734

No catalog. Other books available include:

Kearns, Martha. Käthe Kollwitz: Woman and Artist

Kollwitz, Hans, editor. The Diary and Letters of Kaethe Kollwitz

Prelinger, Elizabeth. Käthe Kollwitz

Upcoming anniversary exhibition in Cologne will have a catalog.

Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln

www.kollwitz.de

October 29, 2010-January 16, 2011

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Sunday, May 16th, 2010 Print This Post

Sunday, May 16th, 2010

Multimedia Master William Kentridge

Animates the Museum of Modern Art

& the Metropolitan Opera

Those fortunate enough to secure tickets for the all-too-brief run at the Metropolitan Opera of Dmitri Dmitrievich Shostakovich’s 1928 opera, The Nose, produced and designed by artist William Kentridge, could later carry their ticket stubs to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) for a 50 percent discount off the admission price to see William Kentridge: Five Themes, though to digest the entire feast required a second trip.

Born in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 1955, Kentridge grew up in the midst of apartheid. Early on he joined in the struggle to end it, cofounding at age 20 a theater company to stage works of resistance–writing, producing, designing and acting in many of the plays. Since 1978 when he created his first animated film, Kentridge has used theater, film and the graphic arts to address political, social, personal and artistic issues.

The extravaganza at MoMA presented a cornucopia of treats that started with the 1989, mostly charcoal and chalk, Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris, first in the series, Drawings for Projection; continued on to the present with the artist’s visualizations of his own creative process featured in the studio scenes of 7 Fragments for George Méliès (2009); and encompassed the puppetry, staging and music for The Magic Flute (2003) and animation and dance films for The Nose (2010).

The man who has produced this huge, wide-ranging body of work has this to say about his work habits: “Walking, thinking, stalking the image. Many of the hours spent in the studio are hours of walking, pacing back and forth across the space gathering the energy, the clarity to make the first mark…It is as if before the work can begin (the visible finished work of the drawing, film or sculpture), a different, invisible work must be done” (exhibition wall text).

Aptly illustrating that description of his struggles, one of the 7 Fragments, depicts Kentridge wandering back and forth in front of a drawing of a hat tacked to his white studio wall while papers fly into his hands as if by magic. Projected in reverse, all of Fragments casts the artist as sorcerer, giving drawings a life of their own. In another of these endlessly looping short films, a torn, three-quarter length portrait of Kentridge reassembles, comes to life and walks away.

Much like writers who claim they don’t control their characters, Kentridge confronts a drawing that changes itself. In Movable Assets, another part of Fragments, trees fall off the page, the entire image morphs and ultimately dissolves completely as the artist tries in vain to catch it in the act. He redraws it with gestures of wiping it off, a trick made possible by running the film backwards.

Kentridge, a magician, makes things appear and disappear. A trickster, he plays loose with notions of reality and representation. A shape-shifter, he seamlessly transforms objects. Those skills are most evident in the animated films about Felix and Soho (1989-2003), composed of mostly charcoal drawings, erased and redrawn with pentimenti as witness to the process. In Thick Time: Soho and Felix, the Tide Table segment (2003), cattle waste away to skeletons and turn to rocks in the surf while Soho, the suited businessman, reclines in a beach chair and military types on a balcony survey the scene through binoculars.

Those who missed the show at MoMA can still see excerpts from the films online, listen to the artist discuss his work, and read a bit about his life. Unfortunately, no catalog accompanied the exhibit. The next time a Kentridge production comes to a theater or museum nearby, waste no time in buying tickets and scheduling a visit, the only way to truly savor this polymath’s work.

Catalog:

William Kentridge: Five Themes

Mark Rosenthal, editor.

(Includes a DVD created by Kentridge

for the book.)

Available at Amazon.com for $31.50.

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Tuesday, March 16th, 2010 Print This Post

Tuesday, March 16th, 2010

The Lost World

of Old Europe

By about 30,000 years ago, homo sapiens had driven Neanderthals to extinction, crowding them out of central Europe, driving them further and further south until they had nowhere else to go but gone. Not long after that, humans were forced south too–by advancing glaciers from the north.

With the end of the last ice age, around 11,500 years ago, peoples inhabiting the Levant began a steady migration north and by 6,000 BCE had settled in southeast Europe along the Danube Valley stretching from what is now Serbia to Ukraine. In the exhibition, The Lost World of Old Europe: The Danube Valley, 5,000-3500 BC, at New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, archeological treasures, mostly from Bulgaria, the Republic of Moldova, and Romania, tell the incomplete story of the various Neolithic cultures that thrived during these times.

Were they matriarchal Goddess worshipers? A majority of unearthed figurines (the term for these small sculptures) depict women; representations of men are rare. A cache of 21 figurines with 13 chairs upon which the larger sculpted women can sit has been called, “The Council of the Goddess.” If the two prongs on the back on one chair represent bull horns, then the grouping becomes a reference to a fertility cult.

In the exhibit, a descriptive caption elaborated on “the ubiquitous” sculptures of women nursing babies “in the Neolithic period…as evidence of a cult dedicated to a goddess of Birth and Nurturing and to rituals associated with the renewal of life.” But not so fast, subsequent wall text cautions: “the great variety of contexts in which [all types of female] figurines are found (burials, households, hoards, and sanctuaries) suggests that they might have assumed different social, cultural, and even religious connotations.” This seems to strengthen rather than diminish the likelihood that the feminine was highly revered in these cultures, lending additional support to the idea these were matriarchal societies.

A stunning female figure from Hamangia (Romania) characterized a particular style. Of fired clay, about 8″ tall, with protruding breasts, arms that run alongside the chest and across the belly, wide hips that taper into legs the shape of which echo the long, headless neck, the sculpture could easily have been used in rituals of fertility. The long neck, a bit like a skewer, begged for a piece of fruit or bread to be stuck on it, which would have heightened its association with nurturing and fecundity. But since the figures in “The Council of the Goddess” as well as some others had long necks with pinched clay noses and gouged out eyes, probably it was a stylistic quirk, akin to the Mannerism of a much later time.

Other arresting sculptures come from Cucuteni. Armless with prominent shoulders, tapered waist, large hips and narrowing legs ending in small feet, they are wrapped by parallel scoring that emphasizes their shapes. There is a simplicity and elegance about them.

Though many mysteries still remain about the uses of these figurines, as objects of art they stand on their own and are well worth seeing.

The Lost World of Old Europe:

The Danube Valley, 5000-3500 BC

Institute for the Study of the Ancient World

New York University

15 East 84th Street

New York, NY 10028

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Thursday, March 11th, 2010 Print This Post

Thursday, March 11th, 2010

Sideshow:

The John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art

Sarasota, Florida

Ducking into the Ringling Museum of Art during the opening night outdoor festivities, I was refreshed by the blast of cold air and taken aback by a very large, very green, abstract painting vaguely reminiscent of Willem de Kooning’s slashed women. It hung between two portraits: on the left, a woman in an iridescently painted gown; on the right, Joshua Reynold’s John Manners, Marquis of Granby (1766), depicted standing with his arm draped over his horse’s ass.

My companion, there to review the Arts Festival and remembering some advance publicity, attempted an explanation. The contemporary works were supposed to relate to the historical works adjacent to them. We figured the key here was the color, relating it to that shimmering gown. Surprise! Surprise! It was Lord Manners and his horse.

Louise Fishman Among the Old Masters, curated by Virginia Brilliant (snippets of whose rationale I overheard on a subsequent visit as she guided three women around the museum), “interjects” the artist’s “lean abstract paintings with muscular blocks of color” into six of the museum’s galleries, engaging in a dialog with their selected twins. It seemed to me not so much a conversation as a major disagreement.

This juxtaposition of the old and the new underscores the amount of craft entailed in producing old masters’ works. Although much of the Ringling’s collection doesn’t reach greatness, even the B work required more refined technique than Ms. Fishman’s abstract musings. Full disclosure: I’m an artist working in the realist tradition who loves the Italian Baroque and my idea of truly accomplished abstract art looks like that of Gerhardt Richter, a man who knows what to do with paint.

The Ringling had two other special exhibitions through which I wandered. One was Dangerous Women, billed as an examination of the 16th and 17th centuries’ fascination with “the exotically (and oftentimes meagerly) clad Biblical [sic] temptresses, Judith and Salome” who sometimes merged into one sword-wielding or -commanding beheader (read castrator) of men. Two paintings come immediately to mind: Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes (1598) and Artemisia Gentileschi’s work of the same subject, Judith Slaying Holofernes (1612-13). While I didn’t expect to find either of them in this modest show, I was disappointed there were no reproductions. On the other hand, I appreciated the inclusion of Fede Galizia’s Judith with the Head of Holofernes (1596), a painting I knew about but had never seen. Of the two versions that exist of this work, I’d want to see this one first, for here the artist has signed her name on the sword; on the other, her signature appears on the tray holding the severed head, a very different message.

I had more to choose from in Venice in the Age of Canaletto where I made other new acquaintances and renewed contact with old ones. I’ve never been a big fan of Caneletto, nee Giovanni Antonio Canal (1697-1768), whose work seems too studio bound, lacking the quality of Venice’s unique light. Francesco Guardi (1712-1793), on the other hand, and even the lesser known Bernardo Bellotto (1721-1780)–both following on the heels of Canaletto–display the animation, color and chiaroscuro missing in the older painter’s works. Two pieces by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696-1770), a fresco, Allegory: Glory and Magnanimity of Princes (1757-61), transferred onto canvas and an oil on canvas modello for a larger work, The Miracle of the Holy House of Loreto, showcased his draftsmanship and colorito. Several fine paintings by Sabastiano Ricci (1659-1734), active much earlier than Canaletto, introduced me to his work.

Completing my peregrinations around the museum, I noted with excitement work such as Peter Paul Rubens’s The Triumph of Divine Love (c.1625), a huge masterpiece just inside one of the museum entrances off the courtyard. Showing the figure of Charity in all her Rubenesque voluptuousness surrounded by and holding babies, this one looks autograph. The rest of the large paintings from the commission for which this was painted suggest a busy workshop, upon which Rubens surely depended.

Most of the permanent collection in the Ringling Museum of Art reflects a collector lacking a Bernard Berenson to guide his selections but who nonetheless occasionally got lucky. Currently in the process of developing a fund for acquisitions and limited by a small conservation department with a long to-do list, the museum (owned by the state of Florida and managed by Florida State University) has great potential. Ms. Brilliant and company are working on bringing the museum into the 21st century for which I wish them the best in these difficult economic times. One can never have too many museums of art.

The John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art

Sarasota, Florida

Posted in Art Reviews |

|

![Plate 18, The Difficult Secret [Front] for site](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Plate-18-The-Difficult-Secret-Front-for-site-217x300.jpg)