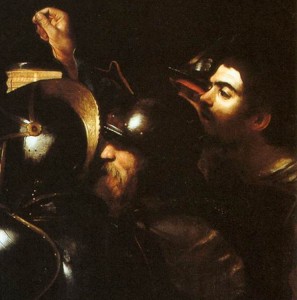

An Unlikely Master,

Caravaggio Brings Light

To the World of Painting

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Taking of Christ (detail) (1602, oil on canvas, 135.5 x 169.5 cm). National Gallery of Ireland. Courtesy of the Jesuit Community, Leeson St. Dublin. Photograph © National Gallery of Ireland.

In 1610 in the Italian coastal city of Port’Ercole, at the all-too-young age of 38, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio succumbed to either malarial fever (historically preferred version) or violence (supported by newer research).1 He left behind several paintings on a boat wending its way without him (another story) to his patrons in Rome and more critically, a new way of painting that had already changed the practices of many of his contemporaries, and would continue to inspire artists in the near and distant future.

In the spring of 2013, Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art hosted the final stop on an international tour of the exhibition, Burst of Light: Caravaggio and His Legacy. The multi-venue show, which grew out of a collaboration among the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Atheneum and several French museums, displayed a selection of works by Caravaggio and his many followers that could be seen in its entirety in the finely illustrated catalog but only enjoyed in part at each site.

For the movie-going, novel-reading public, facts and fantasies about Caravaggio’s tumultuous social life might be better known than the significance of his contributions to the practice of figurative painting. Two well-attended gallery talks in the space of a few hours on a beautiful Saturday afternoon in June demonstrated that given the opportunity, a contemporary audience could be captivated by the images that centuries ago first attracted fans.

A visitor asking at the Atheneum information desk for directions to the exhibit was told that straight ahead at the top of the grand staircase was a room with the Caravaggios and on either side of it, ones with the work of other artists. Unlike with the usual blockbuster that sprawls over an endless succession of galleries, the close proximity of these 32 paintings allowed for comparisons among them via a short walk from one to the other.

Only four of the five Caravaggios originally slated for the show were on display. Apparently the Metropolitan Museum of Art had decided to hold onto its jewel, The Denial of Saint Peter (1610), for the spring opening of its new European painting galleries. A late work, the painting demonstrates how far the master had gone in his ability to pick out light from darkness with just a few deftly applied swipes of high-value color.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy (c.1595–96, oil on canvas, 36⅜″ x 50¼″ [92.5 cm x 127.8 cm]). Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut.

In the right half of the painting, Caravaggio’s light draws attention to the action as it lands on the angel’s face, upper body and right hand (which tugs on the rope around the saint’s habit), and Francis’s face and hands. Following the sweep of the brown cloth brings the viewer to a bright spot that opens up the rest of the scene where a man curled in a fetal position leans against a tree and props up his head with his hand, perhaps sleeping, unaware of the drama taking place nearby.

Behind him several much smaller figures gather around the bright spot–a fire–intent on something outside the picture on the left. Further back, light of unknown origin, either from an unseen full moon or a spiritual presence, illuminates a body of water.

The tenderness with which the spiritual being gazes upon and cradles in his arms the ecstatic mortal borders on a far more profane tableau of post-coital bliss. The barely open, unfocused eyes, slightly upturned corners of the mouth, and limp body of the saint remind the viewer of the thin line between religious ecstasy and sexual arousal.

That double entendre was probably not accidental. Caravaggio ran with a wild bunch of like-minded painters in Rome and when not working in his studio to “destroy the art of painting”2 with his rebellious naturalism, managed to repeatedly come into conflict with the law. As unconventional with his sexual behavior as he was with his brush, the great iconoclast enjoyed an intimate relationship with one of his young followers nicknamed Cecco del (as in belonging to) Caravaggio. An accomplished artist in his own right, Cecco modeled for his master and accompanied him on his travels.3

Caravaggio, having lost his father at age six and a brother several years later, sent by the time he was thirteen to live in the house of the painter with whom he apprenticed, then having his mother die when he was nineteen,4 arrived in Rome at age twenty–a young man with a history of many losses and maybe even exploitation. Born in Milan in 1571 as Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, this fledgling artist soon after his mother’s death cashed in his inheritance and headed to Rome where, within the next few years, he found a wealthy supporter and developed a revolutionary style of painting.

Proclaiming Nature as his teacher, Caravaggio painted from life; he found his models among the street people he met on his usual rounds and portrayed them as they appeared–without idealization. Using a single source of light that raked across figures placed in a shallow, dark space without an identifying context, the artist sometimes encountered outright rejection of his in-your-face realism when one patron or another refused to accept a commissioned piece (usually one bound for a church). But the look caught on and others emulated it, though none except perhaps Jusepe de Ribera came close to wielding a brush the way this virtuoso could.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Martha and Mary Magdalen (1595–96, oil and tempera on canvas, 39⅜″ x 53″ [100 x 134.5 cm]). Detroit Institute of Arts.

The curve of Mary’s red-satin-clad right arm leads to a white flower held close to her heart and onwards to the yellow sash that ends at a sponge in a bowl near a comb, all of symbolic value. Open-mouthed Martha, in the midst of a debate with her sister, enumerates her first point with brightly defined hands. Her shadowed face and far more sober attire attest to her attachment to good deeds as the path to spiritual attainment in contrast to Mary’s preferred life of contemplation.

The purple of Mary’s dress, green of the cloth near the mirror, and variety of hues of Martha’s attire, painted in large areas of local color, would continue for a while in Caravaggio’s early paintings and later be supplanted by mostly monochromatic images with an occasional bright red section, perhaps because of the high cost of other pigments.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Salome Receives the Head of Saint John the Baptist (c. 1606–10, oil on canvas, 36″ x 42″ [91.5 x 106.7 cm]). The National Gallery, London.

Similar in style and format to The Denial of Saint Peter, the Salome seems to have been cut off on the left. A few more inches on that side would bring it closer to the three-by-four proportion of the Denial and other Caravaggio paintings. Also, although identified as Salome, the woman receiving the head is entirely too dressed down to be the seductress of myth.

At this point in his career, Caravaggio painted with light. Notorious for having left behind few if any drawings, he scratched his ideas directly onto a wet underpainting and built upon that with observations from life. In the Salome, unhesitant brush strokes of almost pure white describe the folds in the cloths and pick out the highlights on the cross-like sword. The few notes of warm color can be seen in the slight blush on Salome’s face and in the sun-exposed visage of the executioner, in the still-flushed ear of the saint’s head and the neat little trickle of blood below it, pooling in the dish. The artist’s true genius can be found in his ability to model barely perceptible form in very dark shadows.

Early on, Caravaggio’s rapid rise to artistic prominence in Rome, along with his notoriety, attracted the attention of the many other young artists who had come to the ancient city in search of fame and fortune. Among them was Bartolomeo Manfredi (1582-1622), who adopted his teacher’s tenebrism and half-length figures set in dramatic, often violent, tableaux, and eventually influenced future generations of artists with what came to be known as the Manfrediana methodus.5

Bartolomeo Manfredi, Christ Crowned with Thorns (c. 1620, oil on canvas, 33″x 44″ [82.6 x 110.5 cm]). Michele and Donald D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, Massachusetts.

Neither Manfredi nor most of the others desirous of cashing in on this much-in-demand new style of painting could approach Caravaggio’s drawing ability and paint handling. Where the master’s brushstrokes demonstrate the same swaggering self-confidence that was his undoing in the streets, Manfredi’s reveal the effort required to accurately render his intentions.

Orazio Riminaldi, Daedalus and Icarus (c. 1625, oil on canvas, 52″ x 37″ [132 x 96.1 cm]). Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut.

Ostensibly, Riminaldi has illustrated the myth of the architect of the Labyrinth, imprisoned with his son in his own creation, who fashioned wings from wax and feathers to enable their escape, and is here seen affixing them to the boy, who will fly too close to the sun and perish. Interpreted by some as an allegory of the risks of creative genius,6 the subject affords this artist an opportunity to exquisitely contrast the freshness of youth with the weathered appearance of maturity.

The wrinkled skin on the forehead of the older man, his tan and muscular right arm, and the prominent veins on the hand holding the wing are set against the curly hair, silky smooth pale complexion and less developed musculature of the boy. The brightly lit, perfectly painted flesh of the latter’s thigh, the softness of which is alluded to by the nearby downy feathers, invites the viewer to caress it.

Taking away the wings and the title, one sees a much older man about to embrace a rather fey, nude, prepubescent boy who supports himself with his right arm as he leans back, perhaps in response to the pressure of the other between his legs. Riminaldi discreetly draped a red cloth down the front of the man’s body to avoid the appearance of skin-to-skin contact in the area of the youth’s genitals. The boy’s raised arm, which provides freer access to his body, parallels that of the man’s and avoids direct contact with it.

Riminaldi’s compositions indicate substantial knowledge of Caravaggio’s paintings, primarily via Orazio Gentileschi (1565-1639) and Manfredi but also from Simon Vouet (1590-1649).7 Much more challenging to trace was how Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652) came to incorporate in his own work the tenebrism and brute naturalism of Caravaggism.

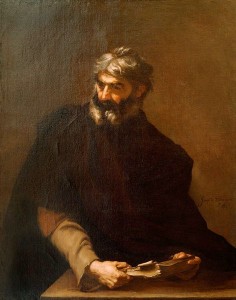

Jusepe de Ribera, Protagoras (1637, oil on canvas, 48⅞″ x 38¾″ [124 x 98 cm]). Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut.

Tucked away in a small room where visitors could thumb through the exhibition catalog and other relevant books was Ribera’s Protagoras (1637), a prime example of Roman lessons well learned. Luminescent thanks in part to direct lighting, this exquisitely drawn and painted oil places in a nondescript setting a three-quarter length figure whose hands hold a book that abuts the picture plane. Other black-infused canvases from these later years, epitomized by the 1637 Apollo Flaying Marsyas, demonstrate the continued appeal to Ribera of Caravaggio’s use of starkly lit figures in the depiction of suffering, martyrdom and death.

Simon Vouet, The Fortune Teller (c. 1620, oil on canvas, 47″ x 67″ [120 x 170 cm]). National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

In Vouet’s reading, the shining smile of the fancily dressed woman on the right, who makes eye contact with the audience, directs attention to the unfolding events. An astounding interplay of five hands in the center of the composition distract the eye from the missing three hands of the expected eight possible among four actors.

The scruffy looking guy with the strange mouth rests his right hand on the lady’s shoulder in a too-familiar gesture, points at her with his other hand, and looks toward the other man who raises a finger in a just-a-moment pose while ransacking the gypsy’s shoulder bag for means of payment. The lack of jewelry (other than a simple ring) on the well-dressed woman adds yet another clue that she is not some wealthy woman visiting a poor neighborhood to find out her future. The fortune teller seems poised to drop a coin into the extended hand while looking across at its owner with the slightly raised eyebrows of curiosity and expectancy.

Lest anyone miss the joke, Vouet painted a red sash on the brown-skinned woman’s bag, leading the eye straight to the action. Likewise, the high-value white of the fortune teller’s blouse in contrast with the dark tone of her skin draws focus to the right side of the painting and the man in the shadows behind her. Each facial expression adds to the drama played out by three-quarter length figures set close to the picture plane in an indeterminate setting lit in typical Caravaggesque fashion.

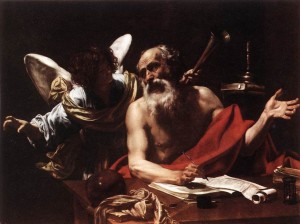

Simon Vouet, Saint Jerome and the Angel (c. 1622, oil on canvas, 57″ x 70″ [144.8 x 179.8 cm]). The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

Arriving trumpet in hand to announce to Jerome his imminent death, the curly-haired angel with its sweet smile of compassion encounters the busy scholar in the midst of his work transcribing ancient Greek and Hebrew biblical texts into Latin.9 Jerome turns from his work, makes eye contact with his visitor and raises his left hand as if to say, “Give me a break! I’ve barely made a dent in this stuff.”

Vouet choreographs the figures within a diamond shape, the top point of which is the angel’s left wing and the bottom the foremost corner of the table, lying just beyond the picture plane. All but one of the their combined four arms synchronize with each other in their movement upwards. The rebellious exception remains adamantly planted on the desk, its hand poised to continue writing if given the chance.

Despite wrinkles, receding hairline and long white beard, Jerome sports the musculature of a much younger man. The red drapery against which his left arm must work to achieve levitation serves to define part of the lower left side of the diamond while doing nothing to cover that by-now-familiar, well-lighted, bare male shoulder.

Some of the abilities that made Vouet so successful in Rome are apparent in his modeling in the dark of the angel’s face and his skill in rendering a great variety of textures, especially the characters’ hair and skin. Never fully wedded to Caravaggism, however, this artist went on to paint in other styles.

Nicolas Tournier, The Denial of Saint Peter (c. 1625, oil on canvas, 63″ x 94″ [160 x 240 cm]). High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia.

On the left, Peter denies to the soldier about to arrest him that he knows Christ. On the right, another soldier watches three colorfully dressed men in a game of dice. The beautifully painted sword that adorns the one in the skin-tight leggings and blousy, yellow shirt, and the hilt of another peaking out from the dice player who stares with wide-eyed, open-mouthed alarm at the events unfolding nearby, bring to mind the artists who originally ran with Caravaggio; they also carried blades and often got into street brawls. Perhaps Tournier’s idea was to show on one side a biblical scene a la Caravaggio and Manfredi, and on the other, the artists who looked closely at their work.

This multi-figured composition contains plenty of action along an arc that begins with the head of the sleeping disciple on the left and travels through all the heads to the back of the young man on the far right. Tournier adeptly portrays facial expression and packs into the painting lots of opportunity to display his talent for depicting texture, from hard, shiny armor to coarse cloth, and throws in a pail of very convincing burning coals for viewers’ enjoyment. While his artistic model was Caravaggio, unlike the master, Tournier applied paint in thin and carefully applied layers to slowly build up form and define surfaces.

Francisco de Zurbarán, Saint Serapion (1628, oil on canvas, 475/16″ x 4015/16″ [120.2 x 104 cm]). Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut.

Zurbarán brilliantly summarizes the martyrdom of Serapion–by crucifixion, beheading and quartering–in the pose. The slumping saint’s body held up by ropes that fix his outstretched arms above his head represents death on the cross. His head falling to the side, disconnected from his body by the hood of his habit, suggests decapitation. And the securely tied rope around his right wrist references his quartering.

Lacking the usual bloody drama of Caravaggesque martyrdom scenes, Zurbarán’s almost square composition provides a sense of stability. His placement of the saint’s head in repose on his right shoulder and the calm look on his face have little in common with the theatrics found among other works in the exhibit.

By affixing to the canvas with a tromp l’oeil pin a torn scrap of paper with his signature in ultra thin lettering, and rendering the red and yellow shield of Serapion’s monastic order in a decidedly unrealistic fashion, Zurbarán calls attention to the artifice of painting. Unlike the three-dimensional drapery folds, and the hands and head of the figure, the shield–with its central placement and sole use of color in this monochromatic picture–loudly calls attention to the two-dimensional nature of the canvas by appearing to float on the picture plane rather than be attached to the robe.

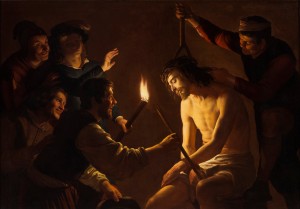

Gerrit van Honthorst, Christ Crowned with Thorns (c. 1617, oil on canvas, 51⅜″ x 67⅜″ [146 x 207 cm]). Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Taking compositional ideas from Manfredi and company, particularly in his choice of subject matter,12 tenebristic lighting, undefined background and zoomed-in view, van Honthorst followed his own path in the material execution of the painting. Figures are contained within their own contours. Fabrics are devoid of identifying details. And brushstrokes are barely detectable. He differed too in his choice of body types for his figure of Christ, which lacks the buff male body with its bared shoulder(s) so popular among the Roman crowd.

Instead, van Honthorst’s mocked man, with sad resignation, gracefully submits to the humiliation and physical pain being forced upon him; though he bows his head, he doesn’t resist the thorns being implanted there. Slightly slumped forward, Christ accepts the stick placed in his hand by one of his tormentors, a man whose open-mouthed laugh, wrinkled brow and wide-open eye express a sadistic enjoyment rarely depicted among Christ’s torturers.

Georges de La Tour, Old Man (c. 1618–19, oil on canvas, 35⅞″ x 23″ [91 x 60.5 cm]). The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, California.

Georges de La Tour, Old Woman (c. 1618–19, oil on canvas, 35⅞″ x 23″ [91 x 60.5 cm]). The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, California.

Unlike the first of those (de La Tour’s much later candlelit scene of The Magdalen with the Smoking Flame [1638-40]), the other two–a pair of full length figures, Old Man and Old Woman (c. 1618–19)–were far from Caravaggesque. These striking portrayals of an elderly couple lack most of what had come to be associated with artists inspired by the works of Caravaggio.

The man, whose painting was displayed to the left of the woman’s, supports his weight on a walking stick, leans over as if to peer around the picture frame, and casts a sidelong glance at the woman in the other picture. The object of his gaze stands with hands on hips–perhaps removing the apron that falls away as her left hand slips under it–and looks back at him with her mouth open, as if in midsentence.

De La Tour made the man the more colorful subject, with his green jacket, orange-red pants, yellow leggings and suntanned skin, and indicated his age with a bald head, grey hair, white beard and need for a stick to prop him up. For the woman, the artist used stark white for her hat and blouse without benefit of modifying colors, a flat green with revealing bits of brown underpainting for the bodice of her dress, and a golden hue for the fold-creased apron that covers most of a burgundy skirt, a sliver of which turns lavender under the light on the left. Giving her far fewer wrinkles than her mate, the artist somehow still managed to convey her seniority.

In each painting, de La Tour made the background dark for the lighted area of the figure and lighter for the shadowed side. The man’s right leg hides the point where diagonal lines meet convincingly to indicate a corner at the base of the walls. The woman’s body covers most of the edge where dark walls meet light ones, but the horizontal line running along their base would destroy any illusion that this is a corner were one to look too closely at it. In his skillful rendering of an elderly woman in the midst of an interaction, de La Tour manages to provide enough distractions for the viewer not to notice.

The inclusion of de La Tour in an exhibit on Caravaggism demonstrated just how far afield Caravaggio’s groundbreaking approach to figurative painting reached, extending its spread throughout Europe over the next few hundred years. One man’s impulse to transmute his inner turmoil into art resulted in a new way of constructing images, one still practiced in the present by artists who place emotionally expressive, ordinary characters within tenebristically lighted settings, and assign them roles in emotionally and/or spiritually significant stories, hoping to engage their audience in the contemplation of the often violent drama of human relationships.

_________________________________

1 Spike, John T. Caravaggio (New York: Abbeville Press, 2001), 239.

2 Papi, Gianni. “Some Reflections and Revisions on Caravaggio, His Method, and his ‘Schola’” in Caravaggio and His Legacy, ed. J. Patrice Marandel (New York: Prestel Verlag, 2012), 14.

3 Ibid., footnote 21, 30-31.

4 All biographical information from Spike, Caravaggio.

5 Marandel, J. Patrice. “Caravaggio and His Legacy” in Caravaggio and His Legacy, 13.

6 Zafran, Eric. “Orazio Riminaldi, Daedalus and Icarus” in Caravaggio and His Legacy, 62.

7 Ibid.

8 Papi, 24-26

9 Exhibit object label.

10 Caravaggio and His Legacy, 78.

11 Ibid, 109.

12 Ibid, 118.

Burst of Light: Caravaggio and His Legacy

The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

600 Main Street

Hartford, Connecticut 06103

(860) 278-2670

Catalog available.