From Bad Boy to Artist

Eric Fischl Finds His Way

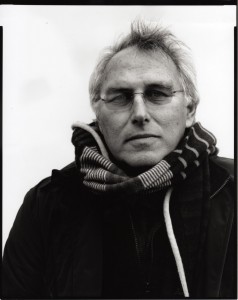

- Book jacket front. Photo of Eric Fischl © 1993 by Gérard Rondeau.

In consciousness raising groups in the early 1980s, women uncovered rape and incest as common themes in their lives. During the same period, adult children of alcoholics, supported by alcoholism treatment professionals, began meeting to explore their shared trauma of growing up in dysfunctional families. Around the same time, unrelated to either movement, illustrations of these survivors’ stories graced the walls of an art gallery in midtown Manhattan.

As he later revealed, Eric Fischl [2]–the artist who created these works–gained his terrible knowledge about such experiences at home as a child. In an earlier book on his work,1 he described at length the split between what his family looked like from the outside (white, upperclass, suburban) and how tumultuous and ugly it was behind closed doors.

Fischl’s new book explores in greater depth life with a mother whose drinking dissolved boundaries between her and her son and created tension with her husband that violent outbreaks served to discharge. Written with Michael Stone, Bad Boy–My Life On & Off the Canvas charts the artist’s journey from tumultuous childhood to the relatively peaceful life the artist now enjoys.

Fischl never intended to write an autobiography; that was Stone’s idea. It grew out of their conversations about the art world in the 1960s when Fischl was attending CalArts with guys whose names would later become synonymous with high-priced, hyped products that most critics came to call art. Encouraged by his publisher to feature an artist, Stone convinced his friend to be the subject.2

The title of the book comes from a 1981 painting that established Fischl as an artist of note–and notoriety. By the time he painted Bad Boy, he had already developed what would be his usual method of approaching a canvas. Starting with “an image or the scrap of an idea”3 he would ask himself journalistic questions to set motivated action within a scene, adding objects and/or characters as answers emerged.Working in the time-honored tradition of arranging figures in a narrative context, Fischl dared to be different at a time when novelty for its own sake ruled and abstraction was ascendent. Unable to emotionally connect to nonrepresentational imagery, he struggled dejectedly for several years before painting his way into a more authentic style4 while teaching art at a school in Halifax in the early 70s.

Fischl writes about the inevitability of that transition with the self-reflection of someone who has done enough personal work to achieve the necessary distance from his process of healing to comment on it. “Feelings lodged in my subconscious were driving my work toward a form of expressiveness that was raw and graphic and troubling–and sometimes cathartic…images would pop out that were increasingly recognizable both as people and things, avatars of my buried past.”5

With the local fishing community of Halifax to provide inspiration, Fischl began painting stories about a fictional family he called the Fishers who eventually morphed into the Fischls. Using smooth glassine sheets, he would begin by painting in black an object–or person–then ask himself what/who else was present and what might be going on, letting his unconscious lead his brush.

In his explanation of effective narrative painting, Fischl inadvertently also describes the impact of trauma. “Working toward that moment…the frozen moment…pregnant with some special kind of energy…Finding where to arrest the action…to stop time…The most dramatic moments are the moments just before or just after something happens.”6

With much the same power, a traumatic event freezes time for anyone trapped within it, especially a child. Overwhelmed by a flood of emotions–primarily terror–and unable to safely integrate within the psyche the awful truth of the moment, the victim’s brain sequesters this unknowable information within the amygdala (a brain organ that among other related functions regulates negative emotions) and effectively stops time, dissociating fragments of the experience in the service of survival.

Those traumatic memories, because they have not been metabolized, are subject to spontaneous, experiential recall. When Fischl writes, “[m]y portrayals of the Fisher family and their daily dramas had begun to trigger memories of my own childhood,”7 he was describing how something in the present reminiscent of the original traumatic event can call out the raw feelings–sensory and emotional–and hurtle the survivor back in time, forcing the body to react as though it were happening all over again.

Fischl’s creative process, which evolved over time to include photographs that he manipulated in much the same was as he used the glassines, provided a way for him to process and integrate the dissociated memories of a boyhood spent in a violent, alcoholic family, and an entry into manhood marked by the suicide of his mother when he was 21. The material that found its way onto his canvases was ambiguous enough to enable him to paint it and relevant enough to his own history to give meaning to experiences that can never really make much sense.

Bad Boy and its companion paintings of a darkly erotic nature soon attracted the attention of the art-buying world and Fischl, joining Mary Boone’s stable of artists, found himself hobnobbing with celebrities and making money. He describes at length the unfortunate transformation beginning in the 80s of an art-appreciating art world into a highly commercial art market; art became a commodity, to be bought and sold like any other investment. In his coverage of that period, Fischl critiques the novelty-based productions of other artists whose work, like his, was selling like hotcakes.

Thrown into the social and quite artificial environment of art openings, feeling undeserving of the accolades and financial rewards that were accruing, Fischl ran into serious trouble with alcohol and the then ubiquitous cocaine. How he wrenched himself free of addiction’s grip after a road rage encounter, the story of which opens the book, owes a great deal to his relationship with April Gornik [4], an artist in her own right, his girlfriend at the time and now his wife.

Fischl’s clumsy initial attempt to score with this woman of his dreams (by insulting her work) reflects how wounded he still was from the turmoil he had not that long ago escaped. Not surprisingly, within a few paragraphs of that anecdote he writes about his father’s attempts to keep the family together after his mother’s death.

The artist does eventually get the girl who, once won over, remains loyal. Not an easy thing for two artists to couple and remain so, particularly when the career of one (often the man) advances faster than that of the other. That Fischl and Gornik have managed to forge a lasting relationship speaks to their love for, and commitment to, each other. Eric’s feelings are quite clear throughout the book, the very last word of which (not counting the useful index) is “APRIL.”8

Of great value for art historians and other aficionados, Bad Boy chronicles the development of Fischl’s major projects, from initial idea to final execution. An artist whose work is always evolving, Fischl early on took to photography and eventually acquired enough photo editing skills to add that tool to his kit. One day he picked up some clay to get through a block and ended up producing exciting (and sometimes controversial) sculptures. Influenced by his two-dimensional creations, the sculptures in turn became inspirations for new drawings and paintings.

Along the way, Fischl has forged lasting friendships with others who share his passion for maintaining integrity in artistic expression and are successful in their own areas of expertise. Many became the subjects of portraits. Not unrelated to this honing of interpersonal skills, for the writing of this book he reached out to his three siblings, to friends from his early years, to other artists who knew him way back when and to those who have known him in more recent times, asking each to pen a short piece about him.

Not one to shy away from the truth, Fischl took some risks with those invitations, the results of which are interspersed throughout the chapters under the heading of “Other Voices.” Reminiscent of what partially motivates attendance at high school reunions, he undoubtedly discovered even more about his younger (and older) self than the demands of autobiographical writing ordinarily reveal.

Fischl’s fearless self-scrutiny stands out in his exploration of a painting session that was about to end in frustrated disaster the summer before he transferred to CalArts. It began as an abstraction but soon “ground to a halt.” After “weeks of struggle…[it] culminated in a tantrum.” The artist, from his current vantage point of considerable recovery, links the “frustrating sense of paralysis and unreasoning anger” with “the same feelings [he’d] experienced watching [his] parents fight, being pummeled and tossed aside when [he] got between them.”9

In a fit of rage, Fischl obliterated with white primer the offending area. When he stepped back to take stock of the damage, he saw that he had “painted a white cartoon floating bed,” introducing representation into an originally abstract painting but also eliciting from his unconscious an image that would recur years late in canvases like Bad Boy. Of this he astutely notes, “…the bed alludes to the womb, the birthplace of childhood memory, the place where dreams occur, the setting for sexual fantasies and encounters,”10 but stops short of uttering the still unspeakable word, incest.

At the end of that summer as Fischl continued his struggle to extricate himself from the suffocating confines of his mother’s escalating alcoholism by moving to San Francisco in advance of the school term, his mother, unable to tolerate the departure of her favorite son and close companion, crashed her vehicle into a tree. Having quickly returned home, the young Eric stood helplessly at his mother’s hospital bedside, in time to exchange a few last words with her before she died. Overwhelmed by undescribable feelings, the fledgling artist “vowed that [he] would never let the unspeakable also be unshowable. [He] would paint what could not be said.”11

True to his word, Fischl has painted his way out of the darkness of his early years by adhering to that original promise. In doing so he has given the world a wide array of disturbing images that force confrontation with, and contemplation of, the darker side of human nature.

__________________________________________________

1 Danto, Arthur C., et al. Eric Fischl 1970-2007 (New York: The Monaceli Press, Inc.), 2008. Fischl acknowledges in Bad Boy incorporating about 2,000 words from the interview with Danto.

2 Fischl, Eric. Bridgehampton Library Lecture, August 2, 2013.

3 Fischl. Eric, and Michael Stone. Bad Boy: My Life On & Off the Canvas (New York: Crown Publishers), 2012, 150.

4 Ibid, 85.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid, 101.

7 Ibid, 95.

8 Ibid, 346.

9 Ibid, 35.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid, 38.