The Unique Style of

A Venetian Artist:

Carlo Crivelli &

His Golden Paintings

Andrea Mantegna, Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1450, tempera on canvas, transferred from wood, 15¾″ x 21⅞″ [40 x 55.6 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Bartolomeo Vivarini, The Death of the Virgin (1485, tempera on wood, 74¾″ x 59″ [189.9 x 149.9 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Yet in almost all the work Crivelli signed, he made a point of reminding the world that he was “Veneto” (Venetian).2 Born in Venice in the early 1430s, he left little material evidence of his life there before 1457 court records note his status as an independent master. Sentenced at that time for his affair with a married woman, the young artist spent six months in prison and then, probably not long after his release, left the city. Over the course of his artistic career, Crivelli traveled among and worked within an assortment of cities in the north and Dalmatia, ultimately becoming closely associated with the Marches. He was never again documented in Venice.3

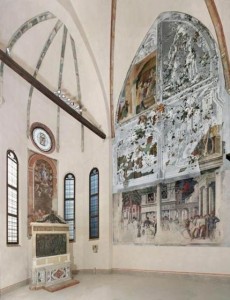

The Met has separated Crivelli from contemporaries linked to his development via Antonio Vivarini’s workshop on Venetian Murano, where he probably received his early training, and Francesco Squarcione’s studio school in Padua, where Mantegna was a rising star.4 As the university town of Venice, Padua was for a time during the mid-1400s “the most creative centre of Renaissance art in all of northern Italy.”5 It drew artists like Vivarini and Mantegna, who worked opposite each other on the Ovetari chapel between 1447 and 1450, and it might have been a stopover for Crivelli as well.6

Antonio Vivarini, Saint Peter Martyr Healing the Leg of a Young Man (1450s, tempera and gold on wood, 20⅞″ x 13⅛″ [53 x 33.3 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Antonello da Messina, Christ Crowned with Thorns (n.d., oil, perhaps over tempera, on wood, 16¾″ x 12″ [42.5 x 30.5 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Antonello da Messina, Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1470, oil on wood (10⅝″ x 8⅛″ [27 x 20.6 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Although Crivelli absorbed some of the lessons of the Renaissance, he remained steadfast in his commitment to tempera, a fast-drying medium that lends itself–even requires–a style reminiscent of pen-and-brush ink drawings. Finding in Mantegna’s work a powerful example of the expressive power of line only served to reinforce Crivelli’s personal preference for outlining forms and using hatch marks to create shadows.

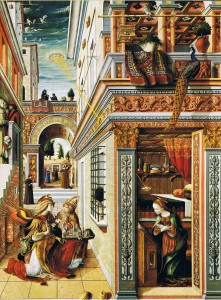

Carlo Crivelli, The Annunciation with Saint Emidius (1486, egg tempera and oil on canvas, 81½″ x 57¾″ [207 x 146.7 cm]). The National Gallery of Art, London.

Carlo Crivelli, Saint George (1472, tempera on wood, gold ground (38″ x 13¼″ [96.5 x 33.7 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Carlo Crivelli, Madonna and Child Enthroned (1472, tempera on wood, gold ground, 38¾″ x 17¼″ [98.4 x 43.8 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Bartolomeo Vivarini, Madonna of Humility (c. 1465, tempera and gold on wood, 23″ x 18″ [58.4 x 45.7 cm]).

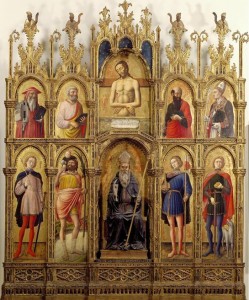

For his 1476 Pietá, a scene of profound grief, Crivelli retained the gold-over-gesso background but toned down his colors in keeping with the somber subject matter. Originally part of a polyptych altarpiece in the church of San Domenico at Ascoli Piceno in the Marches,9 this lunette-shaped panel painting once occupied the position usually reserved for a Christ-Man of Sorrows, as in Antonio Vivarini’s 1464 Pesaro Altarpiece.

Carlo Crivelli, Pietà (1476, tempera on wood, gold ground, 28¼″ x 25⅜″ [71.8 x 64.5 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Here, the left arm of the dead Christ is draped over Mary’s left shoulder while she looks up into his lifeless face with its closed eyes and pallid skin. Her open mouth reveals upper teeth and tongue, as if caught in the middle of an agonized wail, and three large teardrops spring from her right eye. She wears a blue garment edged in reddish gold, damage to the paint surface of which reveals a higher-chroma-blue underpainting and Crivelli’s intentional muting of the overall color key of the painting.

Mary Magdalen appears at Christ’s right, the most colorfully attired of the four figures. Yet her green-lined red cloak, cool-blue dress with gold-embroidered edges, and gold-trimmed red bodice and sleeve were all rendered in a subdued manner appropriate to the narrative. Her golden-red hair cascades in rhythmic ripples from its central part. As she looks down at the wound in Christ’s left hand, three tears drop across her left check and one over her right. Creases form around the left corner of her mouth as she purses her lips, perhaps in the middle of a restrained sob.

In the background, a curly-haired male figure whose youth indicates he is John the Evangelist, opens his mouth and extends his tongue in an almost audible cry. With furrowed brow, lowered eyelids, and three tears coursing from his left eye and one from his right, he looks heavenward as if for an explanation of why this happened to his friend.

Crivelli bunched together his figures, confining them between the arch of the frame above and the horizontal line of the marble ledge below. Only the pierced hand of Christ escapes this claustrophobic space, drawing focus by breaking through the picture plane.

The four figures appear collaged onto the painting’s surface rather than situated in a three-dimensional space. With no indication of the structure on which it sits, the body of Christ mysteriously supports the weight of his mother Mary who throws herself at him in a desperate embrace as his lifeless head leans against hers. On the right, Mary Magdalene holds but does not quite lift Christ’s weightless left forearm. Behind the three-quarter-length figures, St. John the Baptist’s head floats free of a body barely hinted at by its neck and the white-trimmed collar of a brown garment. The flatness of the decorative gold backdrop–including the haloes–presses from behind, leaving little room for the unseen parts of the actors in this drama.

In keeping with his love of line, Crivelli created in this Pietá a symphony of visual rhythms, most obvious in the wavy hair of Christ and Mary Magdalene, the curly hair of John and the narrow bands of folds on Mary’s white head wrap. A spike on the far right of the crown of thorns perfectly overlaps one of the rays of Christ’s halo, and the pointy leaves of the golden background floral pattern further elaborate this theme. Lines pick out the form, with parallel hatching in areas of shadow but also in details like the random, curved lines of Christ’s pubic hair.

Despite Crivelli’s reliance on aspects of an increasingly out-of-fashion Gothic style, he showed interest in contemporary painting practices by using an external light source, which models form better, and dispensing with the use of a spiritual light emanating from one holy figure or another. With the hatch marks typical of tempera painting, he placed shadows strategically. Those below Mary’s right arm fall across Christ’s rib cage and bury in darkness the mildly bloody gash from the soldier’s spear. Those on Christ’s left arm provide a dark ground against which the left hand of Mary Magdalene stands out. Crivelli also used color to direct the eye, relating the green lining of the Magdalene’s cloak to the green of Christ’s crown of thorns, and the white of Mary’s head wrapping to that of the cloth across her son’s thighs.

While the grimacing, teary expressions depict emotional distress, Crivelli understated the traumatic nature of the event by cleaning up the blood from Christ’s forehead where the thorns penetrate below the skin on his forehead and leave evidence of their sharp presence by the mounds they raise. An area of redness is all that remains around the perfectly drawn spike hole on Christ’s left hand, hardly the evidence of torn flesh that would be expected under the circumstances. From Christ’s chest wound–painted to emulate the open mouths of Mary and John–seeps a narrow, transparent stream of blood that trickles down his torso, dividing into three lines that run down his abdomen.

Michele Giambono, Man of Sorrows (c. 1430, tempera and gold on wood, 21⅝″ x 15¼″ [54.9 x 38.7 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Like Bartolomeo’s faces in The Death of the Virgin, those in Crivelli’s Pietá convey the idea of emotion rather than its actual appearance (note the calculated number of tear drops), perhaps in keeping with the humanistic trend of the time. More curious is the lack of believable space in a painting by an artist who established it in other works. Perhaps Crivelli’s goal here was to bring the narrative action as close as possible to the worshiping public by pressing the figures up against the picture plane.

Whatever Crivelli had in mind, in this Pietá he combined the best of his earlier influences with his own unique vision. In this, one of his sparer compositions, he arranged three mourners around the body of a recently tortured and murdered loved one. Their grief-stricken expressions reveal the pain that wracks their bodies while the oddly serene look on the victim’s face shows that unlike them, he is now free of human suffering. It is a picture that could only have been painted by Carlo Crivelli, Veneto.

____________________________

1 Gallery 627 description, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

2 Zampetti, Pietro, Carlo Crivelli (Florence: Nardini Editore, 1986), 12.

3 Lightbown, Ronald, Carlo Crivelli (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 3.

4 Ibid, 4.

5 Humfrey, Peter, Painting in Renaissance Venice (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 53.

6 Lightbown, 3.

7 Hills, Paul, Venetian Colour (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 162.

8 Rushforth, G. McNeil, Carlo Crivelli (London: George Bell and Sons, 1908), 78.

9 Zampetti, 140.

10 The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Catalog entry for “Pietà, Carlo Crivelli (Italian, Venice [?], active by 1457-died 1495 Ascoli Piceno),” 2011. Accessed February 16, 2014. http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/436053.