His Own Artist

Lorenzo Lotto Traveled His Way

On March 25, 1546, Lorenzo Lotto drew up a will in which he referred to himself as a “‘pictor venetiano…de circa anni 66,’”1 helpfully leaving for future art historians the approximate date of birth of an artist for whom secure documentation doesn’t begin until 1503.2 Perhaps feeling the weight of his years prompted that action, for within a few months he was staying in a friend’s house during a period of illness.3

The peripatetic artist was born in Venice and did eventually set up shop there but not before he had already reached middle age (1525) and established a career in such geographically divergent areas as Treviso, Bergamo and the Marches. By then Lotto had also spent time in Rome, working on frescos in the Vatican Palace, though they didn’t stay up for long.4

His reasons for roaming seem to have been to follow the money, but even when prospering he could still be enticed by a job in some distant location. On short notice he would pack up his workshop to reestablish it elsewhere. Nevertheless, except for his time in Rome, Lotto remained within the Venetian sphere of influence, traveling among municipalities in northern Italy and along the Adriatic coast.

Although Lotto probably spent his formative years in Venice,5 the question of his early training has never been definitively resolved. During the last decade of the Quattrocento when he would have been serving as an apprentice, the fledgling artist had a choice of either the Vivarini workshop–active on Murano under the auspices of Bartolomeo’s son Alvise–or the highly productive Bellini enterprise in the city of Venice proper, where Giovanni and his most promising students, Giorgione and later Titian, would eventually develop a uniquely Venetian brand of painting.6

Wherever the teenage Lotto acquired his art education, by the summer of 1503 he was well ensconced in the Venetian city of Treviso7 and within three years was referred to as “‘pictor celeberrimus’ – a very famous painter.”8 He spent the rest of his life filling commissions for altarpieces and small devotional paintings, and becoming one of the greatest portraitists of his generation.

Virgin and Child with St. Peter Martyr (1503, oil on wood panel, 21⅞ x 34¼ inches [55.5 x 87 cm]). Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy.

That sensitivity would remain a part of this artist’s practice throughout a career that spanned over fifty years, appearing at times in the Madonnas and saints that populated his altarpieces and devotional paintings, and finding profound fulfillment in portraits, one of the most powerful of which was Fra Gregorio Belo da Vicenza, produced during the last decade of the artist’s life.

In December 1546, Gregorio sat for a portrait by Lotto in Treviso where they shared membership in the same religious community and probably knew each other well. Almost a year later the oil-on-canvas, almost-life-size portrait was recorded as completed in the artist’s carefully kept account book, the Libro di Spese Diverse (begun in 1538 and kept until 1556, the year of his death).10 The painting now hangs in The Metropolitan Museum of Art where in less than ideal lighting it slowly reveals its genius to the interested viewer.

Fra Gregorio Belo da Vicenza (1547, oil on canvas, 34⅜ x 28 inches [87.3 x 71.1 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A couple of tufts of hair grow from Fra Gregorio’s scalp, and his long beard–with its few flecks of white–blends in with, and disappears into, the front of his deep-brown habit. The pulled-back cloak hood frames the lower half of his head, contributing to the pyramidal shape that imparts maximum solidity to both the composition and the character of the sitter.

Fra Gregorio clenches his right fist, pressing it against himself in emulation of Saint Jerome, whose penance involved pounding his chest with a rock. As a member of the order of the Hieronymites (Poor Hermits of Saint Jerome), Gregorio opted to be portrayed with the attributes of the saint he venerated, taking on Jerome’s behavior and attire.12 The placement of the brightly lit fist on the horizontal midline of the picture, along with the high-value vertical sliver of white sleeve bordering it, underscores the centrality of this hand’s action to the meaning of the painting.

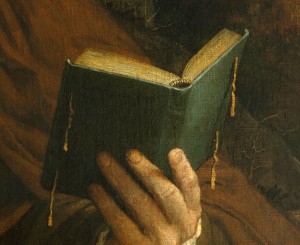

Also lying on the composition’s horizontal midline, Fra Gregorio’s other hand holds open a small book, the lettering of which is imperceptible in the museum’s lighting but which has been identified as the brother’s name-saint Gregory the Great’s Homilies on the Gospels.13 The hand is cradled by the arc created by a sleeve edge painted with the highest value pigment on the canvas, directing the eye to the book above it. The brother leans on a large brown-gray stone block on which is inscribed his name and the date of the work, an additional reference to the sitter’s rock-solid faith and devotion.

The apex of the triangle that is the figure of Fra Gregorio divides the background into two sections connected with an approximately four-inch band of dark, green-blue sky. On the right, a cool light suffuses the clouds near the horizon, perhaps the beginning of a sunrise following a long night of vigil by the suppliants in the upper left who look wide-eyed at a bleeding Christ still nailed to his cross. Summarily painted with small daubs of mostly bright color, the figures of Mary, Mary Magdalene and Saint John the Baptist participate in a scene that seems conjured up by Fra Gregorio as he meditates on Saint Jerome’s years spent in the desert contemplating the crucifix and mortifying his flesh.

In a valley formed by outcroppings of bare rock, dead trees populate a slope visible on each side of the opened book, surely a comment on its contents. By contrast, trees are elsewhere in full leaf, and vegetation covers most of the turf. To the right of the cross a sapling bends at an angle parallel to that of Fra Gregorio’s head, and sparse vegetation on the crest of the hill just to the right of his left ear mimics the tufts of hair on his head, an example of the humorous note often discoverable in Lotto’s pictures.

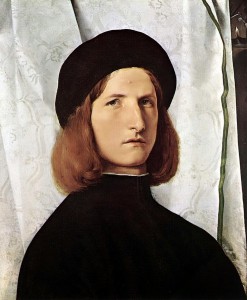

Alvise Vivarini, Portrait of a Man (1497, oil on panel, 24½ x 8½ inches [62.2 x 47 cm]). National Gallery of Art, London.

Youth with a Lamp (c. 1506, oil on panel, 16½ x 14⅛ inches [42 x 36 cm]). Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Those idiosyncrasies worked well for him over the course of the mostly prosperous next twenty years and don’t seem to have been a disadvantage in Venice when, as a 45-year-old bachelor, he returned in response to a promised commission.15 Perhaps hoping there would be more opportunities for him now that Giovanni Bellini, Alvise Vivarini and the still-young Giorgione had passed from the scene, Lotto might have been disappointed to find the younger Titian filling the vacuum with a formidable artistic presence. Nonetheless Lotto stayed, unlike in his younger years when by leaving town he effectively avoided competing with the powerful machine that was the Bellini workshop.

Maintaining his long-standing commercial ties in northern Italy and the Marches, Lotto sought and found new outlets for his portraits and devotional paintings among the citizen class of Venice. Unlike the aristocracy that governed La Serenissima, these merchants and professionals were free to have themselves painted as emotionally expressive, powerful individuals surrounded by possessions that spoke to their interests and personalities,16 very much in keeping with Lotto’s own artistic proclivities. At a time when the commanding Titian arranged subjects in static half or three-quarter-length poses against a dark background, including few if any identifying accessories, Lotto obliged with far more dynamic solutions that seemed in deliberate defiance of that reigning authority.17

Perhaps his nervous personality, religiosity, sensitivity to humiliation and the value he placed on his own work18 led him to jealously guard his artistic independence in the fast-paced world of Venetian artists. As always, he cultivated profitable friendships with members of the local bourgeoisie and for a time was even part of the circle of the Venetian literary lion Pietro Aretino, coming into personal contact with Titian himself.19 Lotto’s willful insularity shows up in the paucity of comments he afforded other artists in his Libro, and in the way he completely left out Titian.20

Strongly apparent in the portrait of Brother Gregorio is Lotto’s open-form manner of paint handling made possible by the advent of oil in the second half of the 15th century. Initially aligning himself with the older generation of Venetian painters who didn’t change their usual practices when they adopted the new medium, Lotto in his early work used well-defined contours to set off figures from their surroundings.

When Leonardo dropped by Venice early in 150021 and brought with him a novel way of conceptualizing figure-ground relationships, his sfumato (smoky chiaroscuro) inspired Giorgione and subsequent artists–Titian especially and Lotto eventually–to blur the edges of form and exploit more of oil’s potential. Likewise, because of the versatility of the still-new medium, painters could dispense with the laborious preparatory process of creating detailed drawings.22 By sketching with brush directly on canvas, they could improvise and spontaneously respond to the image unfolding before them.

The portraits Lotto executed after his arrival in Venice, which are among his best, show his receptivity to this new technique. Like Titian, he painted three-quarter-length figures, but unlike the more successful painter, Lotto portrayed subjects in active communication with their audience, surrounded by objects whose meanings he liked to leave to the viewer’s imagination.23

By 1533, commissions for altarpieces in towns in the Marches once again took Lotto abroad, though he was back in Venice by 1540 and would come and go as business required until leaving for the last time in 1549. At age 72, he retired to the Marian sanctuary in Loreto, accepting care in exchange for occasional artwork. Two years later he joined a religious order and on September 1, 1556, made the last entry in his Libro.24

Berenson opens his final chapter on Lotto’s life with the observation that “[o]ld age is a period in an artist’s life…when old habits are no longer to be changed or new ones acquired…when the man most clearly manifests his native temperament, the almost chemical change it underwent in youth, and what it made of itself in middle age…and the man himself appears with a distinctness never perceived before. As he now stands before us, thus he essentially was through life.”25

At roughly 67 years of age when he painted Brother Gregorio Belo of Vicenza, Lotto poured the intensity of his being into the portrait. In strong identification with his subject, he commanded his brush and paints with a confidence born of years, imparting to the figure and its setting the same determination and force of will, sacrifice and devotion, vulnerability and sensitivity that both served and challenged him throughout his life. Lotto reveals himself in this and many of his other portraits in ways that Titian never could.

___________________________________

1 Peter Humfrey, “Lorenzo Lotto: Life and Work” in Lorenzo Lotto, Rediscovered Master of the Renaissance, David Alan Brown, et al. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 5.

2 Peter Humfrey, Lorenzo Lotto (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 7.

3 Ibid., 153.

4 Ibid., 32.

5 Humfrey in Brown, et al., 5.

6 Bernard Berenson, Lorenzo Lotto (London: The Phaidon Press, 1956), 17.

7 Humfrey, Lotto, 7.

8 Humfrey in Brown, et al., 6.

9 Humfrey, Lotto, 8.

10 Lorenzo Lotto, Il Libro di Spese Diverse, Pietro Zampetti, ed. (Venice-Rome: Istituto per la Collaborazione Culturale, 1963), 74-75.

11 Ibid., 74.

12 The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Catalog entry for “Brother Gregorio Belo of Vicenza, Lorenzo Lotto (Italian, Venice ca. 1480-1556 Loreto),“ 2010. Accessed February 25, 2014. http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/

436917?rpp=20&pg=1&ao=on&ft=Lorenzo+Lotto&pos=1.

13 Ibid.

14 Peter Humfrey, Painting in Renaissance Venice (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 11.

15 Humfrey in Brown, et al., 8.

16 Ibid., 102.

17 Humfrey, Painting in Renaissance Venice, 102.

18 See translations of Lotto documents in Humfrey, Lotto, 176-182.

19 Humfrey, Lotto, 156.

20 Humfrey in Brown, et al., 9.

21 Humfrey, Lotto, 118.

22 Humfrey, Painting in Renaissance Venice, 81.

23 Humfrey, Lotto, 90.

24 Ibid., xii-xiii.

25 Berenson, 111.