City House, Country House:

A Tale of Two Madrasas

After 9/11, many Americans came to associate the religion of Islam with terrorism, and madrasas with the recruitment and training of future terrorists. The early history of these “collegiate mosques”1 or “theological colleges”2 (as they have been called) demonstrates their importance as purveyors of propaganda, a common function of all educational institutions. As developed and deployed by the Seljuks of Anatolia, they served as front-line institutions in the battle to restore Sunni orthodoxy, which had all but disappeared by the time Nizam al-Mulk became vizier and de facto ruler of the Seljuk empire3 in the mid-eleventh century, and embarked on his madrasa-building campaign.

Begun with more modest objectives, the earliest madrasas probably operated out of a teacher’s house. Eventually these places of learning grew in size to provide rudimentary lodging for students (all male, of course) as well as space for daily prayers.4 Under the generous patronage of Nizam al-Mulk and his regime, madrasas sprang up in many of the major urban areas in the Near East to counter the significant advances that had been made by the rival Shi’i who practiced a different brand of Islam.5

In addition to consolidating power through the imposition of Sunni state-sponsored institutions of religion, the newly built madrasas provided training for bureaucrats who would then go on to faithfully serve their government. In this way, Nizam al-Mulk transformed what began as a building for study and prayer into one that was used to train “individuals to maintain order and enforce control and power.”6

By 1146 another ruler, Nur al-Din, was in control, having established his base of operations in Aleppo in northern Syria after political and military maneuvers that arrested and repelled the advance of the Crusaders, contained the Seljuks in the north, and consolidated his authority over an ethnically diverse Near-Eastern population. Himself a Turk from Anatolia with a largely Kurdish following, Nur al-Din turned to the already-established notion of jihad (the political and spiritual struggle against non-believers–in this case the Crusaders) to rally this variegated Islamic populace around shared goals.7

Perhaps inspired by the work of his predecessors the Seljuks, Nur al-Din positioned himself as the commander of the jihadist cause and began a building campaign to restore and erect orthodox Sunni structures throughout his territory, deploying religious education as a glue to hold his lands together.8 In Aleppo, a predominantly Shi’i city, he waited three years before building his first madrasa, al-Halawiyya in 1149, initially avoiding a heavy-handed approach that would jeopardize his popularity and control.9 When he was ready to challenge the Shi’is hegemony, he did it openly, situating this new Sunni madrasa opposite the Great Mosque in the madina, the center of the city.10

At the same time, by choosing to erect his madrasa on the skeleton of the Byzantine cathedral St. Helena–already retrofitted for use as a mosque in 1124–Nur al-Din could further triumph over Christianity.11 While nothing is known about the original plan of the church or the changes made to convert it into an Islamic house of worship, at the time of its conversion into a madrasa (or later) changes must have been made to its physical structure.12

The current appearance or even the continued existence of the al-Halawiyya madrasa remains a mystery. A Syrian civil war attracting foreign combatants has already claimed the lives of many important monuments in Aleppo and elsewhere.13 Tourist reports accompanied by photographs from as recently as 2012 documented a building in use as a mosque, no longer functioning as a madrasa, and in need of serious conservation and restoration work.14

Reports, ground plans and photographs from the 1970s and earlier15 describe a building entered through a portal leading to a long corridor that opened into a courtyard with a pool at its center. Across this modest-size open space, a floor-to-ceiling window topped by an arch faced with alternating black-and-white stones demonstrated the inventiveness and skill of Northern Syrian masons.16

Through the door to the left of the large window lay the remains of the Byzantine church–the main section of the madrasa–beneath a pendentive dome (one of the first of its type in Aleppo), the fine construction of which suggested the architects might have modeled it on what was left of the one for the cathedral.17 Two iwans (rectangular spaces walled on three sides and open on the fourth) branched off the space under the dome to its left and right. Opposite the entrance in a semi-circular apse stood six vintage columns crowned with acanthus-leaf capitals–vestiges of the previous structure.

On the southern wall of the madrasa interior, an intricately carved wooden mihrab–the locus of all prayers–became the object of intense activity in October 2013 when the Syrian Association for the Preservation of Archaeology and Heritage walled it off behind a protective barrier. Dating to the time of Nur al-Din and renovated one hundred years later by an Ayyubid king, it includes verses of the Qu’ran.18

Much later (in 1660), the Ottoman rulers left their mark on madrasa al-Halawiyya with their renovation of the courtyard façades, commemorating that activity with an inscription over the door to the prayer hall.19 Nur al-Din’s own carved calligraphy, lining three sides of the vaulted corridor leading to the courtyard, was left in place.

View of Interior Courtyard with Trees and Pool, Madrasa al-Firdaws. Photo © Creswell Archive, Ashmolean Museum, neg. EA.CA.5850. Image courtesy of Fine Arts Library, Harvard College Library.

Across town and time, another madrasa took shape, one whose fortunes were as affected by its extramural location as al-Halawiyya’s was by its center-city one. Unlike the madrasa in the madina, which was wedged into an already crowded commercial district, al-Firdaws was designed to be a reminder of the paradise promised to the devout,20 with enough space afforded by its southern suburban siting to include several gardens, flowing water and pools.21

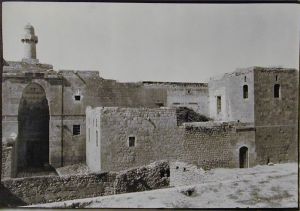

View of Madrasa al-Firdaws from Nearby Cemetery. Photo © Creswell Archive, Ashmolean Museum, neg. EA.CA.5837. Image courtesy of Fine Arts Library, Harvard College Library.

Commissioned early in her regency by Dayfa Khatun, an Ayyubid queen who ruled for her young grandson from 1236 until her death in 1244,22 madrasa al-Firdaws reflected its sponsor’s deep and abiding devotion to Sufism,23 a mystical practice that combined physical deprivation, ingestion of psychotropic agents and dancing. The Qur’anic verses inscribed along the building’s exterior and in a band of text that snaked around three of the courtyard interior walls reminded these worshipers of the vision of God awaiting them as the reward for their asceticism and religious zeal.24 By sponsoring a madrasa that as a center of Sufism functioned as a khanqah25 (“monastic mosque”26), Dayfa Khatun continued the work of a predecessor, Nur al-Din, who during his reign built nine of these Sufi monasteries in Aleppo.27

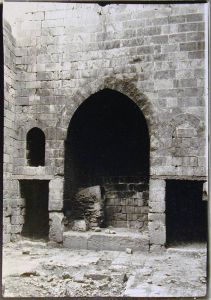

View of Portal on Eastern Wall, Madrasa al-Firdaws. Photo © Creswell Archive, Ashmolean Museum, neg. EA.CA.5840. Image courtesy of Fine Arts Library, Harvard College Library.

The eleven domes of madrasa al-Firdaws and its lengthy inscription along the eastern façade distinguished it from other contemporary Ayyubid religious buildings28 in a way that its otherwise unadorned exterior walls did not. From a distance, the relatively small portal tucked away in the eastern wall seemed insignificant in comparison to the massive rectangle of stone blocks into which it was inserted, but its triple-tiered muqarnas vault capped by a scalloped half-dome29 atop a tall, narrow space, imbued it with a monumentality designed to inspire a sense of awe.

Squinch Arch, Mihrab Dome, Madrasa al-Firdaws. Photo © Çigdem Kafesçioglu, 1990. Image courtesy of MIT Libraries, Aga Khan Visual Archive.

Architects in the Near East developed the “stalactite pendentive”–or muqarnas vault– to solve the problem of mounting a round dome on a square room. Initially using a single squinch arch across each corner to transition from rectangle below to polygon above–and then to dome–architects later used four in a pyramidal configuration. It wasn’t long before these arches proliferated and the muqarnas vault was born.30 In Syria, adept masons carved each separate stone block into shapes destined to fit snugly into place when assembled and to support the weight above them.31 What began as functional evolved into highly decorative multi-tiered constructions, as could be seen in the portal of al-Firdaws.

Once through the doors of this madrasa, visitors encountered a long vaulted corridor leading to an exterior wall of the back-to-back iwans. A turn to the left brought a worshiper to the entrance corridor of the now enclosed iwan that once opened up into “a walled garden with a pool, whose waters were piped into the madrasa.”32 A turn in the other direction quickly revealed the interior courtyard, in its design a symphony of mathematical ratios.33

Islamic architects and artists relied almost exclusively on the science and art of geometry in both construction and ornamentation, using grids in the layout of buildings and in the containment of decorative elements.34 Deploying repetitive, symmetrical and continuously-generated patterns35 (as in fractals), they created designs like that on madrasa al-Firdaws’s mihrab (or prayer niche) with its overlapping and interlacing, multi-colored stonework.

Divided horizontally into three approximately equal sections, the front of that mihrab contained red porphyry, green diorite, and white marble with veins of various colors. Within the semicircular top third, a band of Qur’anic inscription36 wrapped around a circle segment, the innermost part of which was an organized riot of interwoven white lines framing red and green shapes.

In the lower third of the mihrab’s facing, supporting the niche were two granite columns with muqarnas capitals37 echoed by vertical stripes of alternating dark and light marble to their left and right, and continuing into the prayer alcove. Sandwiched between the facing’s top and bottom sections, in a rectangle encompassing the arch of the mihrab’s vault, thick bands of yellow and white marble curved and angled above and below each other; the left side mirroring the right but for the reversal of the overlapping colors, resulting in a not-quite-symmetrical design.

Before entering the mosque (that section of the madrasa that housed the mihrab), devotees first availed themselves of the waters of an octagonal courtyard pool, a complex construction of three layers–an eight-pointed star sandwiched between two octagons–unique to the architecture of Aleppo.38 The stone of the inner perimeter of the basin was carved into scallops alternating with right angles; curves resonated with the hemispheres of the many domes and corners with the surrounding pavement–an arrangement of light and dark masonry in square-based patterns.

Located on opposite sides of the courtyard, column-supported pointed arches opened into vaulted corridors beyond which domed rooms might have hosted gatherings of students and teachers. Perpendicular to these were the prayer hall on one end and on the other, the yawning entrance to the interior iwan, with its evenly spaced niches that at one time could have held books.39

Residence Courtyard with Iwan, Madrasa al-Firdaws. © Creswell Archive, Ashmolean Museum, neg. EA.CA.5859. Image courtesy of Fine Arts Library, Harvard College Library.

Flanking the back-to-back iwans were two-story residential annexes, each with its own courtyard and pool, though of somewhat different configurations. Not visible from the madrasa’s interior space, these areas–since fallen into disrepair–were accessed from the vaulted corridors running alongside the exterior iwan.40 Uncommon in Syrian madrasas, student dormitories41 at al-Firdaws probably reflect that institution’s monastic functions. The minaret rising from this section ensured that calls to prayer could be heard by sleeping devotees, waking them in time for their long nighttime vigils.

View of Madrasa al-Firdaws with Pistachio Trees. Photo © Creswell Archive, Ashmolean Museum, neg. EA.CA.5844. Image courtesy of Fine Arts Library, Harvard College Library.

Unlike in downtown Aleppo, where madrasa al-Halawiyya kept company with the Great Umayyad mosque and busy commercial structures, al-Firdaws had for its nearest neighbors pistachio trees and tombstones. Within walking distance, however, residents and their visitors could, if needed, purchase provisions in a nearby populated area and further away, at the souk (market) of Bab al-Maqam, one of the gates to the city.42

Isolated as the madrasa was, it remained for some time in an active area thanks to the Mamluks–the next rulers of the Near East. As part of the process of restoring Aleppo after the 1260 Mongol invasions destroyed much of the city,43 this new dynasty capitalized on the connection between the center of the city and its extramural neighborhoods. One such focus was a corridor linking the shrine of Abraham on the Citadel with the one South of Bab al-Maqam in the district just north of al-Firdaws, along which they added their own monuments.44

When the Ottomans arrived in 1516, the central and northwestern parts of the city benefited45 from their penchant for erecting expansive complexes encompassing mosque, madrasa, public kitchen, souk and accommodations for travelers46 in those parts of town. This concentration of construction and trade around the al-Halawiyya madrasa helped it maintain its significance, evident in the Ottomans’ seventeenth-century renovations of its courtyard façades.

The emphasis on parts north proved far less advantageous to the madrasa in the southern suburb, which saw the depopulation of its surroundings; even the area cemeteries migrated elsewhere, leaving just al-Firdaws’s own, one of the largest in Aleppo and in the twentieth century, the predominant feature of the immediate environment. What was once a verdant reminder of a paradise to come found itself in a poor, industrial area that profited little from later urban renewal projects.47

In the early twenty-first century, combatants waging war in Syria and its neighboring states have taken the cultural heritage of those countries hostage, already executing too many of the monuments they captured. Air strikes by the United States to drive back an especially malignant faction in the conflicts added to the wreckage.48

Differences in location, function, appearance and history of al-Halawiyya, al-Firdaws and other Aleppian madrasas have ultimately no bearing on their fates. In a corner of the world that has through the ages been in the cross hairs of many conflicts, it remains to be seen what will survive this one and whether restoration and renewal will again be possible.

[For latest updates, click here.]

______________________________

1 Ernest J. Grube, “What is Islamic Architecture?” in Architecture of the Islamic World: Its History and Social Meaning, edited by George Michell (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd., 1978), 37.

2 Yasser Tabbaa, Constructions of Power and Piety in Medieval Aleppo (The Pennsylvania State University Press, Pennsylvania, 1997), 7.

3 Grube, 38.

4 Ibid., 39.

5 Tabbaa in Constructions of Power and Piety, 125.

6 Ibid., 126.

7 Nikita Elisséeff, “The Reaction of the Syrian Muslims after the Foundation of the First Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem” in The Medieval Mediterranean: Peoples, Economies and Cultures, 400-1453, Volume I: Crusaders and Muslims in Twelfth-Century Syria, edited by Maya Shatzmiller (New York: E. J. Brill, 1993), 165-67.

8 Ibid., 168.

9 Yasser al-Tabba, “The Architectural Patronage of Nur al-Din” (PhD diss., New York University, 1982),182.

10 Ibid., 263.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid., 50-52.

13 “Provinces: Aleppo,” APSA (Association for the Preservation of Syrian Archaeology), accessed November 16, 2014, http://www.apsa2011.com/index.php/en/provinces/ aleppo/monuments.html.

14 “Madrassa Halawiyya, Aleppo,” Virtual Tourist, accessed November 16, 2014, http://www.virtualtourist.com/travel/Middle_East/Syria/Muhafazat_Halab/Aleppo-1814607/Things_To_Do-Aleppo-Madrassa_Halawiyya-BR-1.html#.

15 al-Tabba, “The Architectural Patronage of Nur al-Din.”

16 Ronald Lewcock, “Architects, Craftsmen and Builders: Materials and Techniques” in Architecture of the Islamic World, 135-136.

17 al-Tabba, “The Architectural Patronage of Nur al-Din,” 53.

18 “Aleppo: Protecting the Halawiyeh wooden niche 10.06.2013,” APSA, accessed November 18, 2014, http://www.apsa2011.com/index.php/en/provinces/aleppo/monuments/591-alhalaoya-aleppo-2.html.

19 Heghnar Zeitlian Watenpaugh, “The Image of an Ottoman City: Imperial Architecture and Urban Experience in Aleppo in the 16th and 17th Centuries” in The Ottoman Empire and its Heritage: Politics, Society and Economy, Volume 33, edited by Suraiya Faroqhi and Halil Inalcik (Boston, Massachusetts: Brill Academic Publishers, 2004), 183.

20 Yassar Tabbaa, “Geometry and Memory in the Design of the Madrasa al-Firdows in Aleppo,” Chapter 3 in Theories and Principles of Design in the Architecture of Islamic Societies (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture, 1988), 32.

21 Ibid., 28.

22 Tabbaa, Constructions of Power and Piety, 165.

23 Ibid., 176.

24 Ibid., 171-180.

25 Ibid., 8.

26 Graube, 40.

27 Tabbaa, Constructions of Power and Piety, 164.

28 Ibid., 168, 170-71.

29 Ibid., 168.

30 Graube, 124 and 141-142.

31 Tabbaa, Constructions of Power and Piety, 147.

32 Ibid., 169-70.

33 Tabbaa in Theories and Principles of Design, 24-27.

34 Graube, 164.

35 Ibid., 169.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 Tabbaa, Constructions of Power and Piety, 152.

39 Ibid., 169.

40 Ibid., 159.

41 Robert Hillenbrand, Islamic Architecture: Form, function and meaning (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 188.

42 Rana Chalabi, “Madrassa Al Firdaus al-‘Alā” (masters thesis, n.d.), accessed October 17, 2014, http://ranachalabi.com/Chalabi_MA_Thesis.pdf.

43 Ibid., 27.

44 Watenpaugh, 32-33.

45 Ibid., 52.

46 Ciğdem Kafescioğlu, “In The Image of Rūm: Ottoman Architectural Patronage in Sixteenth-Century Aleppo and Damascus,” Muqarnas 16 (1999): 71.

47 Chalabi, 28-29.

48 “Aleppo – Aïn al-Arab-Kobane: US airstrike against ISIS militants on hill of Tell Shair 24.10.2014,” APSA (Association for the Preservation of Syrian Archaeology), accessed November 27, 2014, http://www.apsa2011.com/index.php/en/provinces/aleppo/sites.html.