Identity Dilemma:

Greco-Roman Egyptian

Mummy Portraits at

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

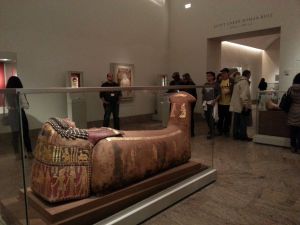

![View of “Young Woman with Gilded Wreath” in Vitrine, Egypt, Roman Period (120–140 CE, encaustic with gold leaf on wood , 14⅜ x 7 in [36.5 x 17.8 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo © Deborah Feller.](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Young-Woman-in-Vitrine-1-225x300.jpg)

View of “Young Woman with Gilded Wreath” in Vitrine, Egypt, Roman Period (120–140 CE, encaustic with gold leaf on wood , 14⅜ x 7 in [36.5 x 17.8 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo © Deborah Feller.

When asked how this work, Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath, came to reside in the gallery of Egypt Under Roman Rule 40 B.C. – 400 A.D. at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Marsha Hill (co-curator of the 2000 show Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt) replied that when the work became available for purchase in 1909 from Cairo antiquities collector and dealer Maurice Nahman, the Egyptian Art Department pursued its acquisition using Rogers Fund money; at the time, the Greco-Roman Art Department expressed no interest in any of the Egyptian panel paintings then appearing on the market. Thus, the circumstances of the artwork’s acquisition largely determined its ultimate context2 and how future museum goers would come to perceive this example of Greek-influenced Roman-era painting.

In the early twentieth century, the Met’s Egyptian Art Department demonstrated impressive foresight with its enthusiasm for artwork from the land of the Nile deemed a “classical development” by most Egyptologists and of little importance to classicists who associated the mummy portraits with Egypt (not Greece or Rome).3 Even in the twenty-first century, a recent book about ancient Egyptian art failed to include any reference to these mummy portraits,4 and an exhibition catalog on Egyptian portraiture concluded with a beautiful example of a Roman mummy plaster mask but failed to mention the contemporaneous and identically used panel paintings.5

Across the Great Hall from the Egyptian wing at The Metropolitan Museum, in the relatively new Greco-Roman galleries, there are only four examples of Greek painting displayed–all small murals and predating by several centuries Young Woman and her kind. One is Lucanian from southern Italy; the other three are from the Alexandria region of Egypt. Whether or not an argument was ever advanced for placing the latter in the Egyptian wing, a case could certainly have been made for exhibiting the Greco-Roman Egyptian mummy portraits somewhere among the museum’s extensive holdings of Roman wall paintings.

When the Ptolemies took control of Egypt after the death of Alexander in 323 BCE, they drained part of the Fayum lake and built an advanced irrigation system to create additional arable land that they then gave to their Greek soldiers, following an already existing practice. Egyptians were later recruited to work on this newly inhabited farmland and after 30 BCE, both these groups were joined by Romans carrying out the business of empire.6 Art like Young Woman, emerging from this conglomeration, was bound to defy easy categorization.

Conceding that they represent a “confluence of Greek painting, Roman portraiture and Egyptian burial practices,” curator Hill explained that an effort has been made to provide a context for the mummy portraits in the room with Young Woman and in the area where the display continues past the nearby gallery-titled doorway. As an example, she pointed to a vitrine there that encases an intact mummy7 intricately wrapped in linen bands with its portrait panel still in place. Rather than serving to emphasize the Egyptian pedigree of these Roman-period portraits, the mummy highlights the startling contrast between the ancient and contemporary burial and artistic practices of its time.

The museum succeeded in situating Young Woman in an Egyptian context primarily through its physical location. Entering the gallery that contains the painting, visitors are introduced to the entire Egyptian wing by a sign containing text and photos highlighting the collection, and an ancient tomb structure from Saqqara. Crossing the large room on the way to the far wall of mummy plaster masks, painted shrouds and panel portraits, they encounter two coffins from the Roman period decorated with images of deities associated with Egyptian burial practices.

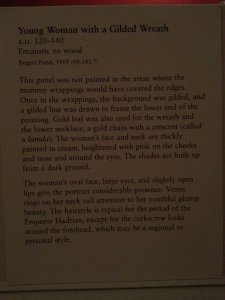

Object Label for “Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath” at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo © Deborah Feller.

Casual viewers attracted to Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath who read the picture’s accompanying label learn nothing of how an object so uncharacteristic of Egyptian art came to be displayed in that wing. The text describes the painting as a work of art–with notes on technique, appearance and dating–and gives nothing of its history.8

Visitors never learn that before being displayed as an art object, Young Woman functioned to ensure safe passage to the netherworld and, consequently, eternal life for its subject. Meant to act as backup in case harm came to the physical self (preservation of the body being essential to the continuation of the ka [spirit]),9 long ago severed from its body and home, now exhibited out of context, the mummy portrait as shown tells an incomplete story.

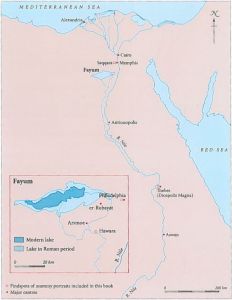

Map of Fayum Lake District from Paul Roberts, Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt (London: the British Museum Press, 2008).

For The Metropolitan Museum, that story probably began in the late 1880s with the rediscovery of mummies with painted faces in the Fayum lake district in northern Egypt. Tempera examples were already saturating the market when British archaeologist, Flinders Petrie, excavating at Hawara in that area, came across a trove of encaustic portraits10–soon to prove more appealing to contemporary Western eyes than the previously discovered tempera ones.11

Most of Petrie’s finds ended up in London at the National Gallery and British Museum;12 some found their way to dealers like Nahman. Over the course of time, mummy portraits were unearthed throughout Egypt, though they still continued to carry the epithet “Fayum.”13 Unprovenanced, if Young Woman did originate from that lake district, the discoverer might have provided a service by rescuing it from likely destruction had its burial place been in the path of mid-nineteenth-century farmland expansion, a response to economic incentives and technical assistance from England for Egypt to produce more cotton.14

The civil war tearing apart the United States in the 1860s had halted that country’s exportation of cotton and created new European markets for Egyptian farmers in the fertile Fayum region. “[F]armers…in search of sebbakh,…Nile mud enriched with human- and animal-produced organic materials”–a cheap source of excellent fertilizer, and raw material for mudbricks and saltpeter (used in gunpowder)15–widened their search for this much prized commodity. As farmland reached ancient settlements, and ruins became more valuable as agricultural resources, farmers lost motivation to preserve and sell unearthed antiquities as was their previous custom.16

While sebbakh was more plentiful around town mounds–not necessarily in the area of necropolises,17 related population expansion and its attendant pressures constituted other threats. Had Petrie and his ilk not excavated and removed these paintings–and in the case of the former, given many to public institutions–the portraits might have been destroyed, or hidden away in private collections, Egyptian antiquities law at the time being as lax as it was.18

In the current century, objects of questionable provenance are increasingly repatriated to the countries from which they were removed,19 and national and international antiquities laws make legal exportation of cultural patrimony almost impossible.20 But up until 1912, Egyptian laws on the books since 1835 allowed for easy acquisition of excavation permits with the proviso that finds be split equally with the state.21

Digging up mummies, separating them from their masks, shrouds and/or panel paintings, and then removing them and their accessories for sale by dealers headquartered in Cairo would have been considered sacrilegious by the elite, mostly Greek and Egyptian early-first-century residents of the Fayum region22 who entombed their dead in accordance with ancient beliefs, but at the time it was happening it wasn’t even illegal. With no constituency left to speak for them, the two-thousand-year-old mummies were fair game.

This contrasts with far more recent twentieth-century disinterments, a potent example of which was the 1991 discovery of human remains in downtown New York City during a “cultural resource survey” that included “archeological field-testing” in advance of the construction of a federal building. Identified as a burial ground for African slaves, the site quickly attracted attention from the African-American community and its supporters. After years of productive research agreed upon by all parties, the long-ago-forgotten Africans were reburied at the original site, now a national monument–the African Burial Ground Memorial.23

Similarly, in 1990 the United States passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, providing a process for the return of Native American remains and their related artifacts already in museum and federal agency collections. The law also set down procedures respecting new burial ground discoveries, acknowledging their spiritual importance to surviving tribes.24

The mummies that Petrie, other archaeologists, treasure hunters and farmers were unearthing in the late 1800s, early 1900s, and even before, don’t seem to have been considered by anyone as ancestral remains. Egyptian statutes governing these practices regulated antiquities dealers, not the treatment of the buried dead.25 When The Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased Young Woman in 1909, the action engendered no controversy, their being no Greco-Roman-Egyptian descendants to make a fuss.

In fact, probably with the motivation to present the mummy portrait Young Woman as a work of art rather than a funerary object, someone had flattened what was originally a convex panel and mounted it on a board. Whether the curve was part of the original form or had developed over time with use,26 the retaining of that bowed shape by the excavator/dealer/collector would have made storage and/or shipping inconvenient, rendering the piece less desirable.

![Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath, Egypt, Roman Period (120–140 CE, encaustic with gold leaf on wood , 14⅜ x 7 in [36.5 x 17.8 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo © Deborah Feller.](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Young-Woman-w-Gilded-Wreath-225x300.jpg)

Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath, Egypt, Roman Period (120–140 CE, encaustic with gold leaf on wood , 14⅜ x 7 in [36.5 x 17.8 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo © Deborah Feller.

If any record chronicled something of Young Woman’s original condition, it would be found in the Maurice Nahman Archives.29 In the absence of such a reference, it seems safe to assume that this portrait panel belonged with others described by Petrie “as [being] fresh as the day they were painted.”30

Displayed to emphasize its aesthetic value, Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath showcases its creator’s skill in the rendering of three-dimensionality, rarely of interest to Pharaonic Egyptian painters. Illumination from the upper left throws warm shadows to the right of prominent forms, while a cool grey tone signals where these forms turn from the light, an effect most obvious along the bridge of the nose and the front plane of the face where it meets the only side visible to the viewer.

Those tricks of the trade surely originated with the great masters of Greek painting chronicled by Pliny the Elder (around 77-79 CE) in Book XXXV of his Natural History31 and took on a new life during the Renaissance, Baroque and later Neoclassical periods of European painting. Nature is not the only teacher here, however. Young Woman’s larger-than-life eyes–like those found on many other mummy portraits–bring to mind ancient Egyptian wall paintings of profile faces with over-sized, kohl-lined eyes.

Viewer in the “Gallery of Egypt Under Roman Rule 30 B.C. to 400 A.D.” at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo © Deborah Feller.

Ordinary museum goers, stopping to admire the dramatically-lit, unusual painting in the corner of a room containing a reconstructed Egyptian tomb, probably wouldn’t notice its finer points of technique nor, because of the way Young Woman is currently presented, would they be aware of the critical function the painting once served. For that matter, no person can know the thoughts of the aggrieved who commissioned the portrait for someone so young32 when seeing it for the first time, probably already held in place by the linen enwrapping the mummified body. In these many ways, the identity of Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath has yet to be fully understood and adequately presented.

____________________________

1 Marsha Hill, Curator of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, interview by author, New York, October 28, 2014.

2 Ibid.

3 Morris Bierbrier, “The Discovery of the Mummy Portraits” in Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt, edited by Susan Walker (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000), 33.

4 Gay Robins, The Art of Ancient Egypt, revised edition (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2008).

5 Donald Spanel, Through Ancient Eyes: Egyptian Portraiture (Birmingham, Alabama: Birmingham Museum of Art, 1988).

6 R. S. Bagnall, “The Fayum and its People” in Ancient Faces, 26-28.

7 Hill, interview.

8 The Metropolitan Museum, object label, Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath, read on October 28, 2014.

9 John Taylor, “Before the Portraits: Burial Practices in Pharaonic Egypt” in Ancient Faces, 9.

10 Nicholas Reeves, Ancient Egypt: The Great Discoveries, A Year-by-Year Chronicle (London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2000), 76-78.

11 Ibid.

12 Bierbrier in Ancient Faces, 32.

13 Ibid., 33.

14 Paola Davoli, “Papyri, Archaeology, and Modern History,” The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri Lecture Series, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, n.d., accessed October 24, 2014, http://tebtunis.berkeley.edu/lecture/arch.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Hill, interview.

18 Davoli, “Papyri, Archaeology, and Modern History.”

19 For example see: Jason Felch, “Getty ships Aphrodite statue to Sicily,” Los Angeles Times, March 23, 2011, accessed November 4, 2014, http://articles.latimes.com/2011/mar/23/entertainment/la-et-return-of-aphrodite-20110323; and Elisabetta Povoledo, “Ancient Vase Comes Home to a Hero’s Welcome,” New York Times, January 19, 2008, accessed November 4, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/19/ arts/design/19bowl.html.

20 “International Antiquities Law Since 1900,” Archaeology, April 22, 2002, accessed November 4, 2014, http://archive.archaeology.org/online/features/schultz/intllaw.html.

21 Davoli, “Papyri, Archaeology, and Modern History.”

22 R. S. Bagnall in Ancient Faces, 28-29.

23 “African Burial Ground Memorial, New York, NY,” Historic Buildings, US General Services Administration, accessed November 8, 2014, http://www.gsa.gov/portal/ext/html/site/hb/category/25431/actionParameter/exploreByBuilding/buildingId/1084#.

24 “National NAGPRA, Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act,” National Park Service, U. S. Department of the Interior, accessed November 8, 2014, http://www.nps.gov/nagpra/mandates/25usc3001etseq.htm.

25 Davoli, “Papyri, Archaeology, and Modern History.”

26 Hill, interview.

27 Ibid.

28 Catalog entry, Ancient Faces, 109.

29 “Maurice Nahman, Antiquaire. Visitor book and miscellaneous papers. 1909-2006 (inclusive),” Wilbour Library of Egyptology. Special Collections Brooklyn Museum Libraries, Brooklyn Museum, accessed November 8, 2014, http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/archives/set/73/maurice_nahman_antiquaire._visitor_book_and_miscellaneous_papers._1909-2006_inclusive.

30 Reeves, Ancient Egypt: The Great Discoveries, 78.

31 Pliny the Elder, Natural History, translated by D. E. Eichholz (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press and London: William Heinemann, 1949-54), Vol. 10, Book XXXV, 38-53.

32 The existence of portraits of young children as well as the very old make it unlikely the paintings were done during the lifetime of the subject, and CAT scans of mummies show age and sex consonant with still-attached portraits. See Susan Walker, “Mummy Portraits and Roman Portraiture” in Ancient Faces, 24.