The Dalí is in the Details:

Mastering the Old Masters

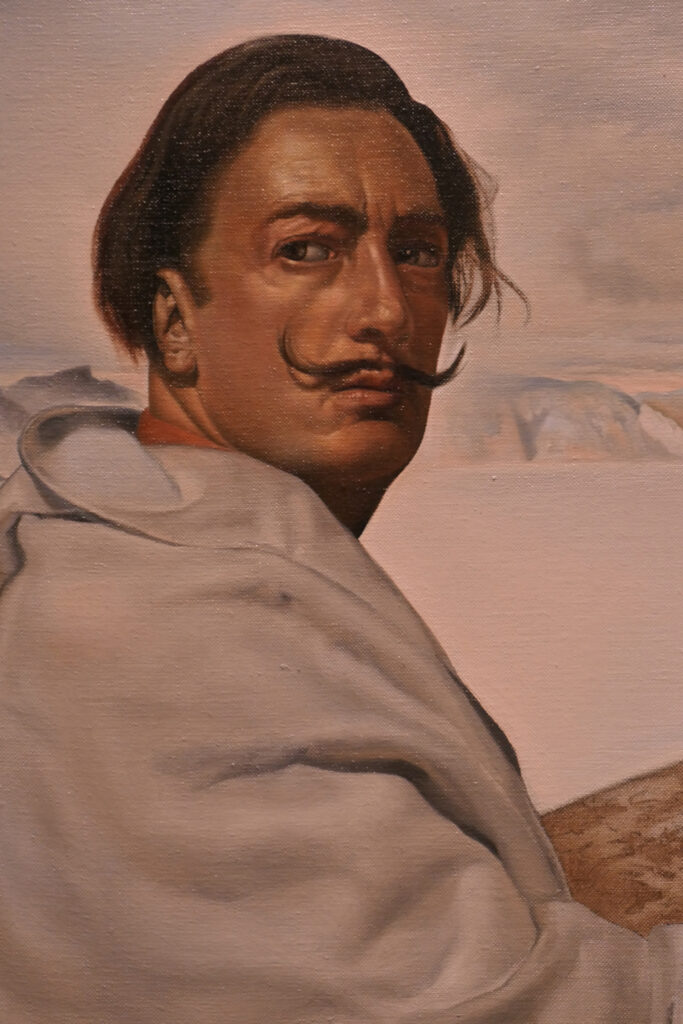

(1960, oil on canvas, 118 x 100 in.

[300 x 254 cm]). Detail of self-portrait.

The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida.

Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse.

Photograph © 2024 D. Feller.

Born in the small Catalonian city of Figueras nine months and four days after the death of a would-be older brother, Salvador Felipe Jacinto Dalí y Doménech struggled to establish his singularity in the eyes of his father, who believed him to be the miraculous reincarnation of the first son, dead before the age of two. Driven by that existential imperative, the youngster now known as simply Dalí (1904-1989) often collided with authority, first at home and later at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. Enrolled in the art school in 1922, he earned a suspension for disruptive behavior three years later and in 1926, when the time came for his exams, the twenty-two-year old declared the board unqualified to judge him, and left. Soon after, Dalí set out to turn his drive for uniqueness into a lucrative career as a highly creative artist and writer.

The artistic skills that Dalí developed during his time at the Academia in Madrid probably owe more to the hours he spent at the Museo Nacional del Prado than to coursework. Enthralled by the masterpieces brushed and etched by fellow Spaniards Francisco de Zurbarán (1598-1664), Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1650), Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828), and Northern Europeans like Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525-1569) and Hieronymus Bosch (ca. 1450-1515), Dalí integrated their lessons into his own decidedly distinct compositions. Recognizing footprints of these old masters and others, like the Italians Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (1475-1564) and Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483-1520), in the work of this twentieth-century master motivated the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston to collaborate with The Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida, on an exhibition called “Dalí: Disruption and Devotion.”

(1952-1954, oil on canvas, 10 x 13 in. [25.4 x 33 cm]). The Dalí Museum,

St. Petersburg, Florida. Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Greeting visitors at the MFA in a dimly lit entrance gallery with black and red decor, a vaguely familiar painting by Salvador Dalí cashed in on the fame of its fraternal twin. Perhaps meant to be the star of an exhibition that was filled with less well known but often more impressive works by the Spanish artist, The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory (Fig. 1, 1952-1954) was among the many loans from The Dalí Museum sufficient unto themselves to draw a crowd. The Persistence of Memory (1931), from which the later painting derived and which is inextricably linked to its creator in most minds, remained at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, its permanent home.

What began with the prospect of a generous loan of paintings from The Dalí Museum developed into an exhibition about Dali’s engagement with Early Modern European art. In an ideal situation, paintings by Dalí would have been paired with those artworks that prompted them, borrowed from the Museo Nacional del Prado and other venues. Since there were no plans for additional loans, the curators dipped into the MFA’s holdings to find useful comparisons. The strength of the Boston museum’s collection allowed for a visually rich immersion in the art of the old masters, mimicking Dali’s own encounters with it. For a more direct pairing, however, there is value in utilizing the wonders of modern technology to borrow from the Prado, and elsewhere, images of the artwork that spoke so powerfully to the fledgling artist, and to display them here.

(1915-1926, gelatin silver print, 5.9 x 9.1 in. [150 x 230 mm]). Museo Nacional del Prado,

Madrid. Photo courtesy of the Museo Nacional del Prado.

The room at the Prado in which Dalí must have spent many hours appears in an early twentieth-century photograph of the Prado’s Velázquez gallery (Fig. 2, 1915-1926). Hanging on the wall, third from the right, is The Infanta Margarita of Austria (Fig. 3, ca. 1665) that inspired Dalí’s Velázquez Painting the Infanta Marguerita with the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory (Fig. 4, 1958).

The Infanta Margarita of Austria (ca. 1665, oil on canvas,

83.5 x 57.9 in. [212 x 147 cm]). Museo Nacional del Prado,

Madrid. Photo courtesy of the Museo Nacional del Prado.

with the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory (1958, oil on canvas,

60.5 x 36.8 in. [153.7 x 93.3 cm]). The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida.

Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Wandering through the palatial spaces of the Madrid museum, eighteen-year-old Salvador found role models to emulate and parental figures to overthrow. Remembering those years, a much older Dalí in 1958 included in the upper left corner of his homage to the other Spanish master and the Prado, a view of a salon-style hang of paintings, in front of which gather assorted classical sculptures (Fig. 5). The sun coming in from upper windows throws rectangles of light onto the gallery floor that become the stripes that decorate the surface of Dalí’s canvas. A figure, presumably Velázquez, stands before a grisaille of the painting of the Infanta Margarita (Fig. 6), whose fragmented ghostly image hovers above the proceedings (Fig. 7).

with the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory (1958, oil on canvas,

60.5 x 36.8 in. [153.7 x 93.3 cm]). Detail of a gallery. The Dalí Museum,

St. Petersburg, Florida. Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

with the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory (1958, oil on canvas,

60.5 x 36.8 in. [153.7 x 93.3 cm]). Detail of of Velázquez painting.

The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida. Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

with the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory (1958, oil on canvas,

60.5 x 36.8 in. [153.7 x 93.3 cm]). Detail of Infanta Marguerita.

The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida. Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Dalí’s signature commands almost as much attention as the figure it underlines (Fig. 4), and the black rhinoceros horns and horse’s head decorating the hem of the Infanta’s skirt add his personal iconography to the memory of a Velázquez portrait at the Prado. Visually translating the Spanish Golden Age painting into his own explosive style, the modern artist inserted himself among the greats.

oil on oak panel, 86.8 x 71.7 in. [220.5 x 182 cm]).

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

Photo courtesy of the Museo Nacional del Prado.

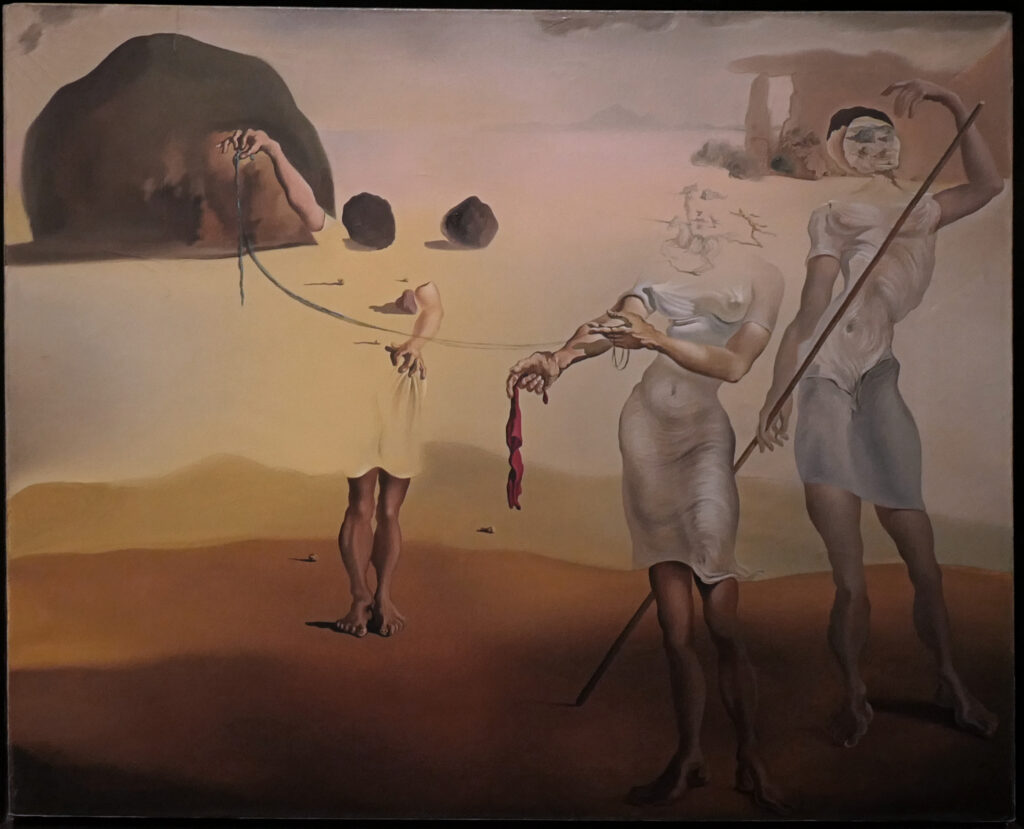

Another revered artist, Fleming Peter Paul Rubens, spent time in Madrid and left behind canvases that include The Three Graces (Fig. 8, 1630-1635), an exercise in portraying various views of a voluptuous female form, candy for the male eye. When Dalí took up the theme in 1938 with Enchanted Beach with Three Fluid Graces (Fig. 9), he posed his female figures facing front, unusual for an artist who often depicted women’s buttocks. Indifferent here to displaying women in the round, he distinguished his Graces by their degree of disintegration. From right to left, their faces and bodies increasingly merge with the enchanted beach.

25.6 x 32 in. [65 x 81.3 cm]). The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida.

Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse. Photograph © 2024 D. Feller.

(1938, oil on canvas, 25.6 x 32 in. [65 x 81.3 cm]).

Detail of bust of center Grace. The Dalí Museum,

St. Petersburg, Florida. Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse.

Photograph © 2024 D. Feller.

Using what he called the paranoiac-critical method, Dalí positioned figures on the beach, including one on horseback, into an arrangement that doubles as the head and face of the central female (Fig. 10). The objects defining the head of the woman on the right and the rock marking that of the one on the left don’t succeed near as well as the one in the middle.

(1497, engraving, 7.5 x 5.2 in. [190.5 x 132.1 mm]). Museum of

Find Arts, Boston. Gift of Miss Katherine E. Bullard Fund

in memory of Francis Bullard. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Lacking The Three Graces by Rubens, the MFA curators found an apt substitute in Dürer’s engraving of Four Naked Women (The Four Witches) (Fig. 11, 1497). Aside from multiplying the number of naked women an artist could justifiably pack into one rectangle, the several sides that Dürer portrayed situate the graphic arts, and two-dimensional media in general, as intellectually superior to menial sculpture, which requires hard labor on the part of both creator and viewer who must walk around a piece to see it in its entirety. This print and Rubens’s painting offer many views at once for leisurely enjoyment. Known as the paragone [comparison], the conflict about the superiority of painting versus sculpture has yet to be resolved.

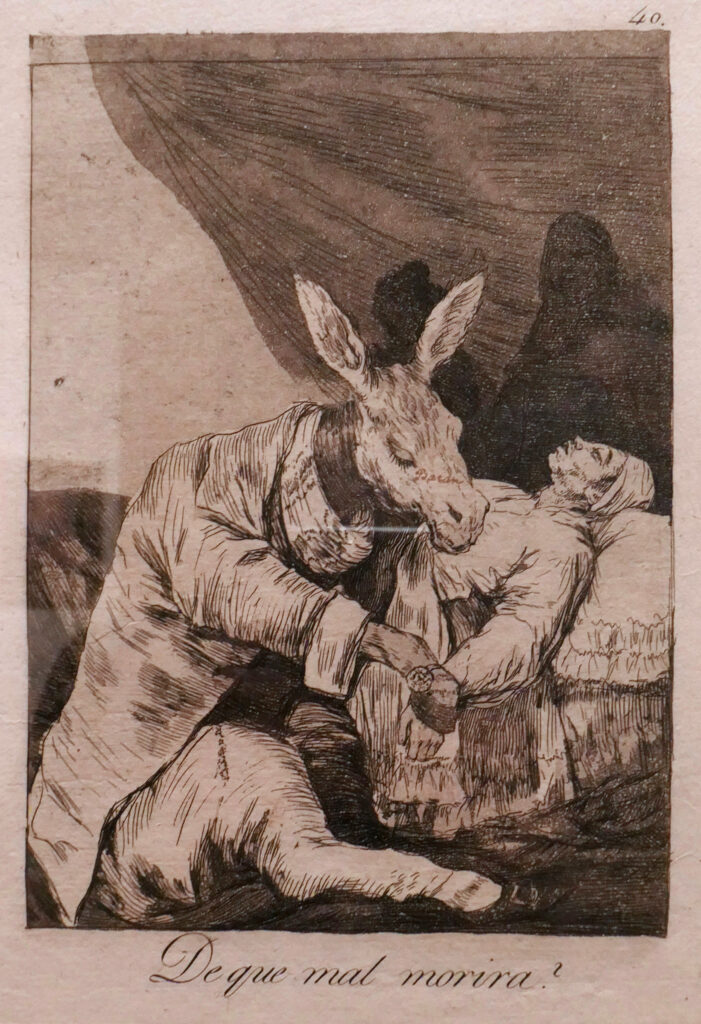

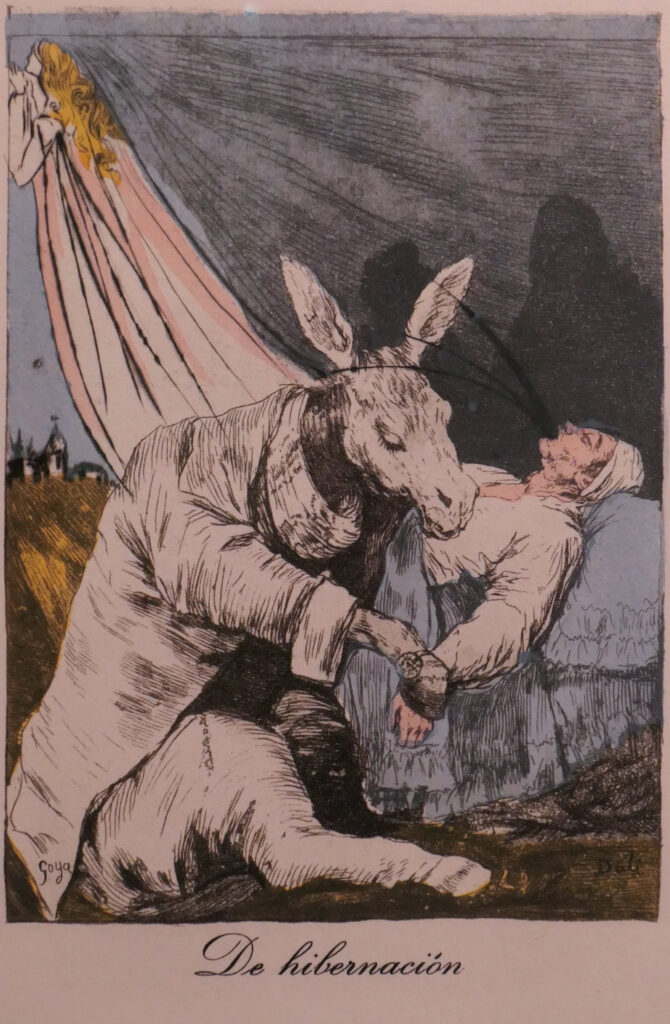

(1797-1798, first edition, etching and burnished aquatint, with annotations

in brown ink, 11.9 x 7.8 in. [301 x 199 mm]). Museum of Find Arts, Boston.

Gift of Miss Katherine Eliot Bullard. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

heliogravure from Goya’s etching reworked with drypoint and stencil coloring,

9 x 6.5 in. [228.6 x 165.1 mm]). The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida.

Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

In a direct invasion of another artist’s work, in the 1970s Dalí spent three years making idiosyncratic adjustments to photogravure copies of all eighty prints from Goya’s series Los Caprichos [The Foibles], some of which were on display alongside the originals in the exhibition. For Goya’s De que mal morira [Of what will you die]? (Fig. 12, 1797-1798), Dalí replaced the subject of death with that of sleep in his remake, De hibernación [Of hibernation] (Fig. 13, 1973-1977). With the primary colors blue, yellow and red, he enlivened Goya’s monographic etching and drew sweeping lines that form the garment of the golden coiffed woman on the left. Below her, Dalí inked either a cross or weather vane on the middle structure of a townscape comprised of three small buildings. Easily overlooked are the three linear projectiles that fly from the hibernating man’s mouth in the direction of the donkey, perhaps a reference to Dalí’s dreams as source material for his ideas.

The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida. Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

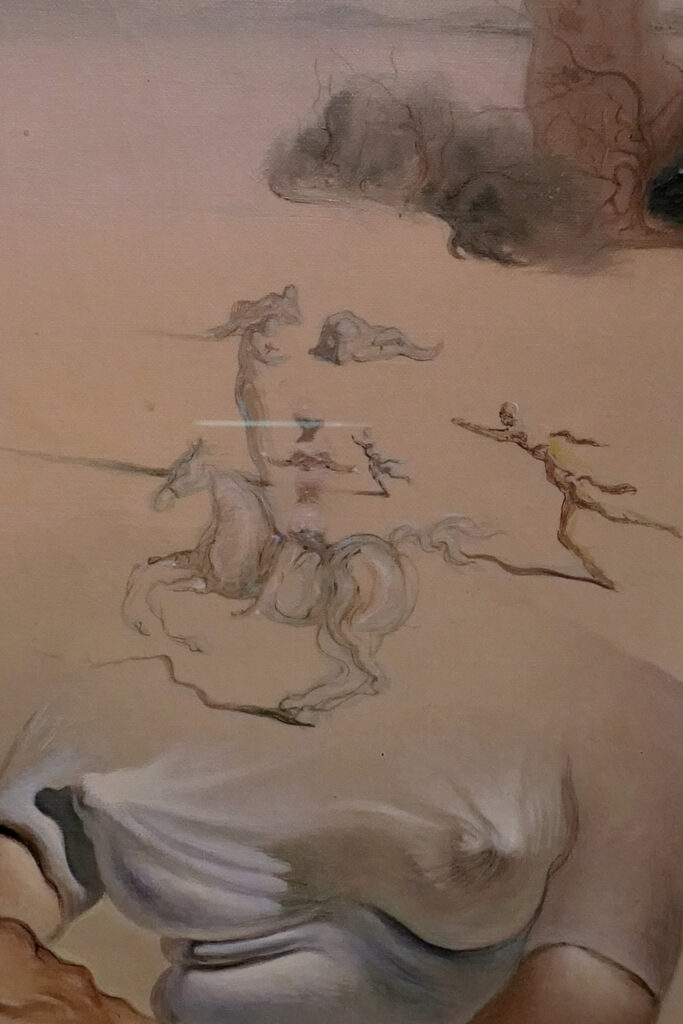

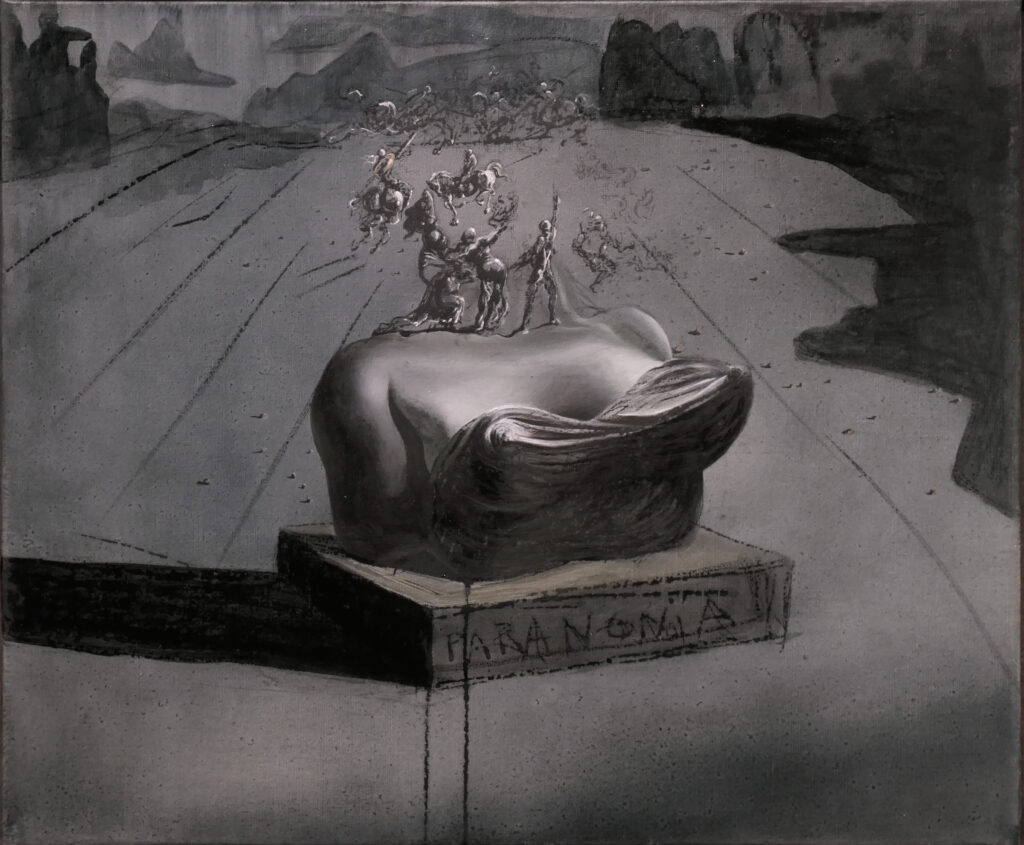

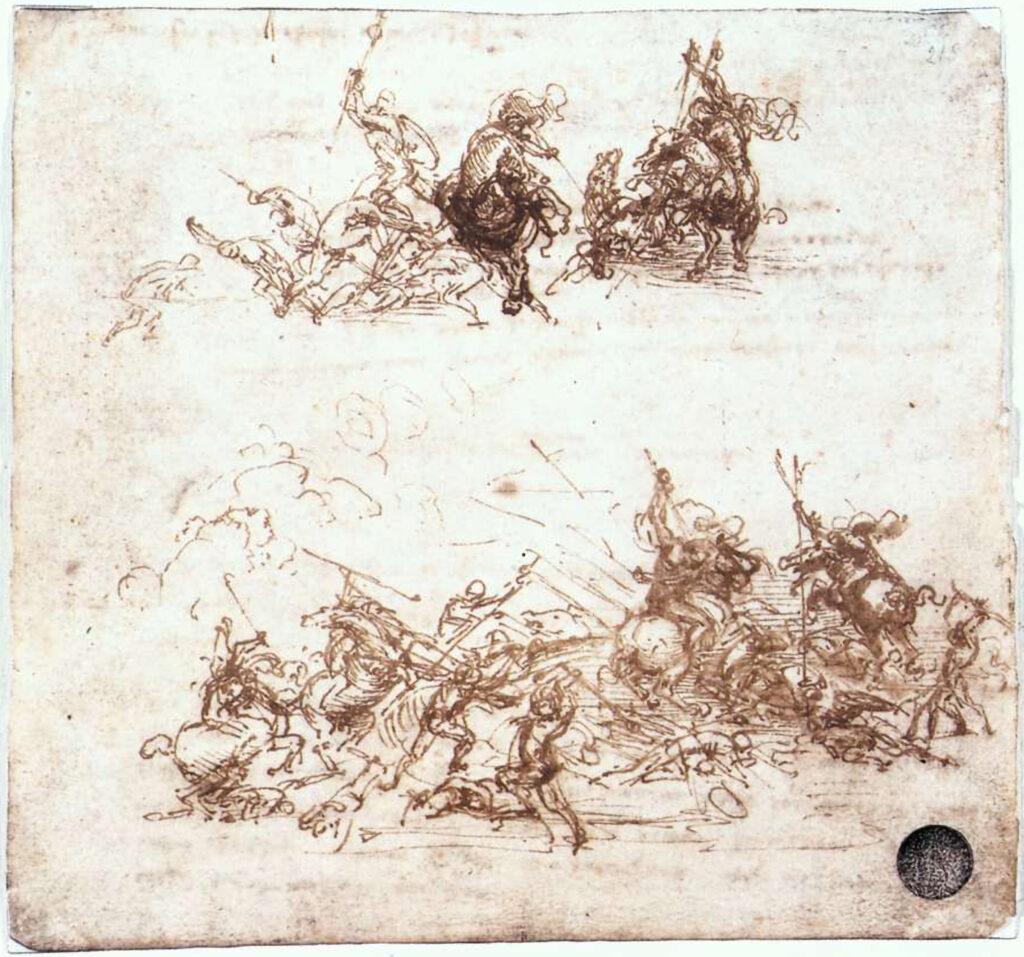

Much less intrusive and considerably more obscure, Dalí’s painting Paranonia (Fig. 14, 1935) subjected to his paranoiac-critical method some drawings by Leonardo, which in the 1930s he would have known from books. In the exhibition, the object label included reproductions of two possible sources, Head of a Young Woman (La Scapigliata [The Disheveled]) (Fig. 15, 1500-1505) and Studies of Horsemen for the Battle of Anghiari (ca. 1503) now at the British Museum. Another sketch, Study of Battles on Horseback and on Foot (Fig. 16, 1503-1504) seems to have more of the flavor of Dalí’s horsemen and is pictured here.

(La Scapigliata [The Disheveled]) (1500-1505,

oil, earth, and white lead pigments on poplar,

9.7 x 8.3 in. [246 x 210 mm]). Galleria Nazionale di Parma.

Study of Battles on Horseback and on Foot (1503-1504,

pen and ink on paper, 5.7 x 6 in. [145 x 152 mm]).

Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice, Italy.

Detail of hidden head of a woman. The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida.

Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

All the figures, mounted or not, are essential to establishing the visage of Leonardo’s young woman (Fig. 17). The negative space outlined by the scampering horses in the rocky landscape and the figures on the bust constitutes the facial skin. The shoulders and outstretched arm of Dalí’s shapely left-leaning female make up the young woman’s mouth. Her head is part of the proper left nostril, and the shadow shaping her buttocks is the contour shadow of the chin. To her right, a male delineates the sweep of the chin by extending his right arm. Meanwhile, the right eye of Leonardo’s young woman emerges from the deep shadow on the nearby well-rounded female facing forward and running toward the left. The dark areas of the profile horse-and-rider make up the left eye, and the rest of the herd fashions the hair. In playing with the well-known Leonardo drawing of a woman’s head, Dalí potentiated the old master’s presence by choosing horsemen on galloping steeds, a reference to the many sketches by Leonardo for his now lost battle painting. Visitors at the exhibition who gathered around the painting helped each other pick out the not-so-easily found Leonardo head.

[55.9 x 64.8 cm]). The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida.

Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

The curators also took advantage of the object label accompanying Dalí’s Two Adolescents (Fig. 18, 1954) to display images of two exceptionally famous works by Michelangelo that served as inspiration for the Spaniard’s provocative painting but could not be moved or simulated by anything in the MFA collection.

(ca. 1511, fresco). Sistine Chapel, Vatican, Rome.

The lithe body of the reclining boy owes its pose to the mortal protagonist in The Creation of Adam (Fig. 19, ca. 1511) on the vault of the Sistine Chapel. Dalí described his adolescent Adam with utmost clarity, to the point of giving him the plentiful pubic hair missing from Michelangelo’s first man. The feature proclaims the youth’s sexual maturity even as his boyish physique and oversized head suggest a younger stage of life. The youngster who posed for Dalí would have no trouble finding work today as a model for men’s underwear.

(1501-1504, marble, height 17 ft [5.2 m]).

Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze, Florence.

Standing on the right, devoid of facial features and with a blurred body, the second adolescent might be a partner dreamed up by the far more substantial youth on the left. Holding a stone in his right hand, he strikes a pose like that of the monumental David carved by Michelangelo (Fig. 20, 1501-1504) that towers over visitors in the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence. At the very least, Dalí took up the challenge laid down by the master of the male body to demonstrate his facility with anatomy, although he surely had other meanings in mind when he conjured up this piece.

118 x 100 in. [300 x 254 cm]). The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida.

Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse. © 2024 Salvador Dalí,

Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society. Photo © Doug Sperling

and David Deranian, 2021. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Obsessed with fitting in among not just the Spanish greats but the Italian ones as well, Dalí found plenty of competitors to best in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes. Having borrowed Adam from the vault, the modern artist later appropriated Christ for his ten-foot-tall Ecumenical Council (Fig. 21, 1960). Taken from the huge Last Judgment (Fig. 22, 1536-1541) that covers the altar wall of the chapel, the imposing nude male figure (Fig. 23) in Dalí’s painting looms over a meeting of mostly mitered religious characters.

(1536-1541, fresco). Detail of Christ. Sistine Chapel,

Vatican, Rome.

118 x 100 in. [300 x 254 cm]). Detail of Christ. The Dalí Museum,

St. Petersburg, Florida. Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Gala, in her guise as Saint Helen, founder of the True Cross, poses for the Spanish artist poised before his virgin canvas (Fig. 21). Facing the viewer as he contemplates his first brushstrokes, Dalí envisions an ecumenical council, no doubt responding to the new pope’s announcement that one would soon be held. Not convened until 1962, the historic meeting of Catholic bishops was called by a new pope the year before the painting was finished. Raised Catholic by his mother but not particularly devout, Dalí professed allegiance to Catholicism after his audience with the pope in 1948, perhaps seeking approval from the epitome of a father figure. Given its own space in the MFA exhibition, the Ecumenical Council commanded the same reverence as an altarpiece.

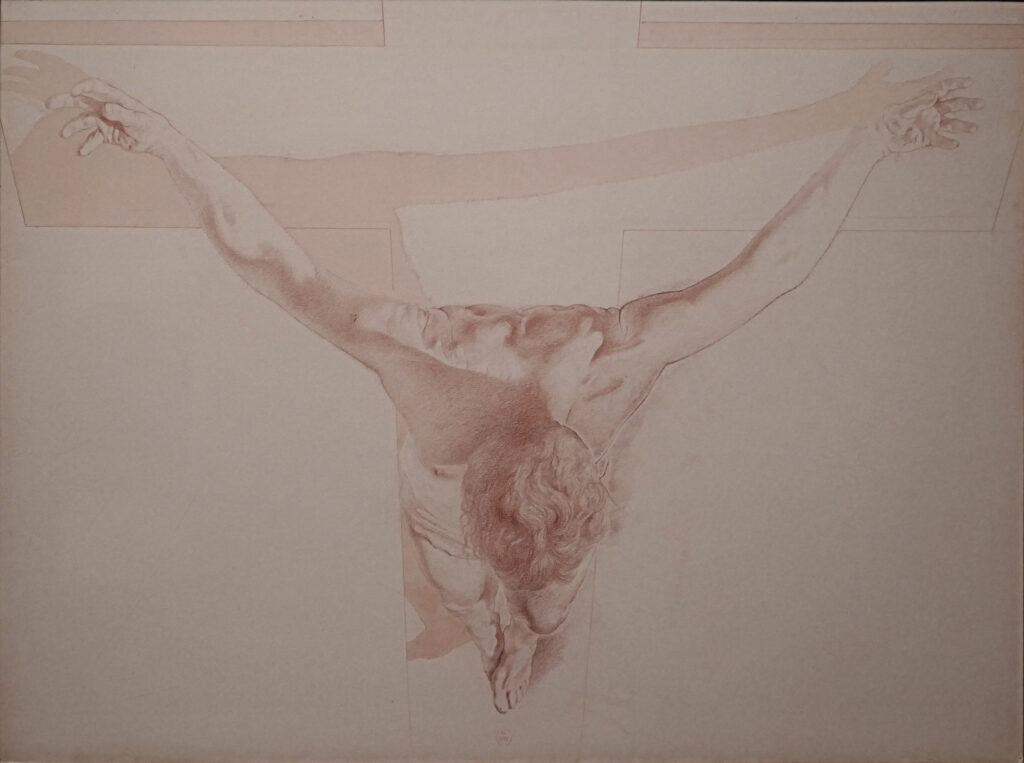

29.8 x 39.5 in. [75.6 x 100.3 cm]). The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida.

Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Other large paintings with religious subjects definitely qualify as altarpieces, albeit for particularly progressive churches or privately funded chapels. Preparatory for one of them, a large drawing called Christ in Perspective (Fig. 24, 1950) attests to Dalí’s superb draftsmanship. From the point of view of God hovering above the crucified Christ, the viewer looks down at an image of perfection lacking the customary torn flesh and dripping blood.

(ca. 1550, 2.3 x 1.9 in. [58.4 x 48.3 mm]).

The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida.

This unusual perspective had its origin in a sketch (Fig.25, ca. 1550) by Saint John of the Cross (1542-1591) that Dalí had seen and that had come back to him in a hypnagogic hallucination during that dreamy period between wakefulness and sleep. Fertile ground from which he harvested endless ideas, that state was the source of his paranoiac-critical method. The highly accomplished painting of Christ of Saint John of the Cross (Fig. 25, 1951) encapsulates the vision he had of Saint John’s cross suspended over Port Lligat, the title acknowledging its source.

80.8 x 45.8 in. [205 x 116 cm]. The Glasgow Art Gallery, Scotland.

As part of his drive to stand out in a crowd, Dalí approached the much less lofty genre of still-life painting with irreverence and wit, very much apparent in his Nature Morte Vivante (Still Life-Fast Moving) (Fig. 27, 1956), which translates literally to Nature Dead Alive. As the wall text in the exhibition noted, this is “Not So Still Life.” A peach and a cherry whiz in from the right, two cups reminiscent of the ancient Greek kylix levitate above a table dressed in bright crimson geometry and traditional white linen. On the left, Dalí’s hand breaks through the picture frame to add a rhinoceros horn to the tumult of misbehaving objects, among which is a glass bottle emptying its contents upwards in defiance of gravity (Fig. 28).

49.3 x 63 in. [125.2 x 160 cm]). The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida.

Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

49.3 x 63 in. [125.2 x 160 cm]). Detail of water spilling.

The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida. Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Despite the visual jokes in this composition and many others, Dalí was deeply serious about his craft. At the Prado he had seen many still-life paintings from all over Europe, like the closely related Table with Desserts (Fig. 29, mid-seventeenth century) by Andries Benedetti (active 1636-1650) with a landscape and broken classical column in the background, white cloth over a green one on a wooden table, and foodstuff scattered amid vessels of varying materials showing off the artist’s skill at rendering textures. To place Dalí’s excursions into this field alongside standard still lifes from Northern Europe and Spain, the curators displayed a number of examples from the MFA collection. This one by Benedetti or another like it at the Prado, however, seems to have moved Dalí to convincingly portray reality as seen with his own peculiar mind sight.

47.6 x 57.9 in. [121 x 147 cm]). Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

Photo courtesy of the Museo Nacional del Prado.

Another foray into this genre, Oeufs sur le Plat sans le Plat (Fig. 30, 1932), a Dalinian combination of still life, landscape and narrative, plays with French words, physical properties and matters of scale, even as it surprises with a man and child in an unfurnished room, peering out a window together. “Oeufs sur le plat” is idiomatic for fried eggs, but word for word means “eggs on the plate” and thus the wordplay occurs in French but not English.

23.8 x 16.5 [60.4 x 41.9 cm]). The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida. Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse. © 2024 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society. Photo © David Deranian, 2021. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

A building bathed in the red light of sunset, probably over Port Lligat, functions as a platform for a plate of fried eggs (Fig. 31) that might remind a viewer of Saint Lucy’s plate of eyes or Saint Agatha’s platter bearing her breasts. The window-shaped highlight on the eggs gives a nod to similar reflections often found on solid surfaces in still lifes but not on squishy ones like the yolk of Dalí’s sunny-side-up egg. To add to the surreality, a thread that begins in the sky beyond the top edge of the picture ends in a knot that secures the white of a dangling egg. The fiery red yolk of that egg looks across at an item related in shape and color, which could be a hot water bottle or a dripping pocket watch, or both (Fig. 32).

(1932, oil on canvas, 23.8 x 16.5 [60.4 x 41.9 cm]). Detail of eggs.

The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida. Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

(1932, oil on canvas, 23.8 x 16.5 [60.4 x 41.9 cm]). Detail of dripping pocket watch.

The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida. Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

(1932, oil on canvas, 23.8 x 16.5 [60.4 x 41.9 cm]). Detail of interior and carrot.

The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida. Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

On the wall above, something suggestive of a carrot guides the eye to a room where a man and boy stand by a window through which shines the golden sky. Painted just a few years after Dalí was angrily disinherited by his father and banished from the family home in Cadequès, the image of the child and grownup might represent Dalí’s dream of a loving father.