A New Audience for an Old Master.

Jusepe de Ribera debuts at the Petit Palais in Paris

[1]

[1]Petit Palais, Paris. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

[2]

[2]Ribera: Ténèbres et Lumière, Petit Palais, Paris. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Leaving the bright vestibule of the Petit Palais in Paris (Fig. 1), where three banners featuring details of paintings by Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652), called lo Spagnoletto, announced the contents of the galleries for the exhibition Ribera Ténèbres et Lumière [Darkness and Light], visitors entered a dimly lit, spacious room with crimson walls and white type (Fig. 2). Here they encountered more blowups from the master’s canvases, a timeline of his life, and a map of the cities he called home. In the crowded space, people jostled for position, intent on reading about an artist likely unknown to many of them.

[3]

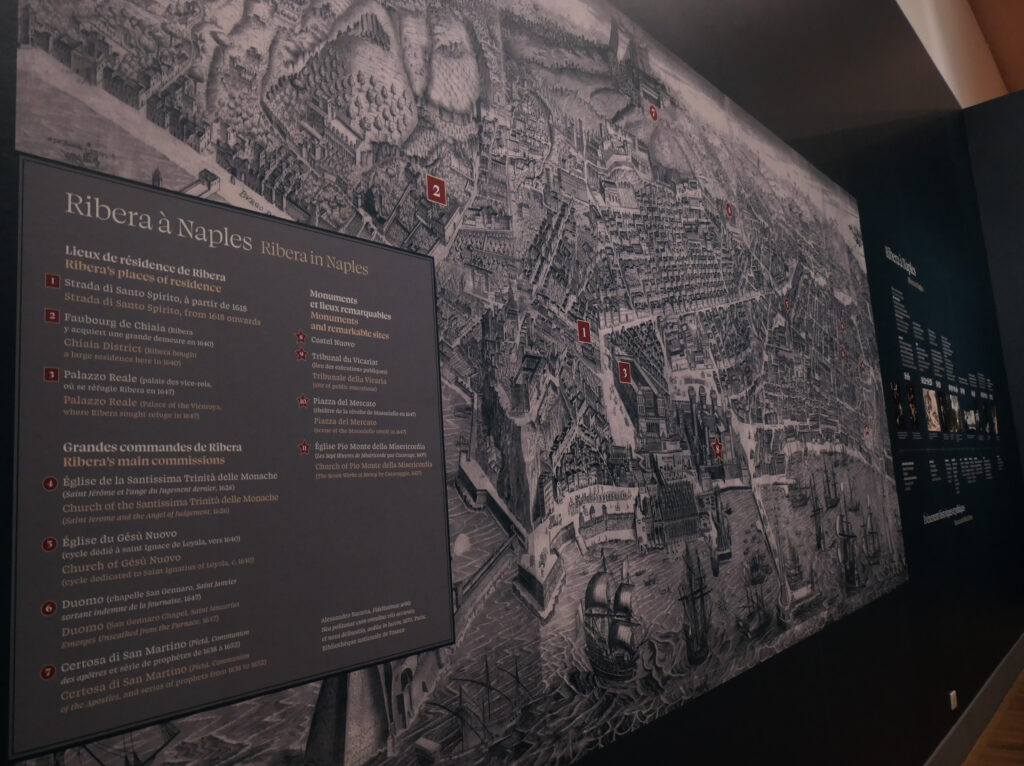

[3]Ribera: Ténèbres et Lumière, Petit Palais, Paris.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Missing from both timeline and map were the three years that Ribera spent in Valencia, where he gained a solid foundation in drawing and painting before boarding a ship that carried him across the Mediterranean to Rome in 1606 when he was fifteen. A possible explanation for that omission appears in the introductory essay to the exhibition catalogue, where mention is made of a lack of evidence regarding the artist’s beginnings in Játiva, his home city.1 The curious reader can consult an article by this author that fills in the gap, “Jusepe/José de Ribera in the Kingdom of Valencia and the workshop of Juan Sariñena: The formation of an artist.”2 Later in the exhibition chronology, a map of Naples marking locations related to Ribera’s time in that city (Fig. 3) lacked the spot where the artist was initially buried, the church of Santa Maria del Parto in the Mergellina district of Chiaia where lo Spagnoletto last resided.

Unlike the wall text, maps and timelines, and almost all of the object labels, which were in French and English, the exhibition catalogue, Ribera Ténèbres et Lumière, is only in French. Sumptuously illustrated with details of paintings and reproductions of the works on view, although not in the order of their display, it includes essays by established names in Ribera scholarship plus a few lesser-knowns. Translations in English, Italian and/or Spanish, in whole or of chapters, perhaps not feasible financially or absent due to a deadline, would have extended the reach of any new scholarship contained in the volume in the same way that the bilingual wall text and object labels allowed a greater number of visitors to learn about the author of the pictures on view.

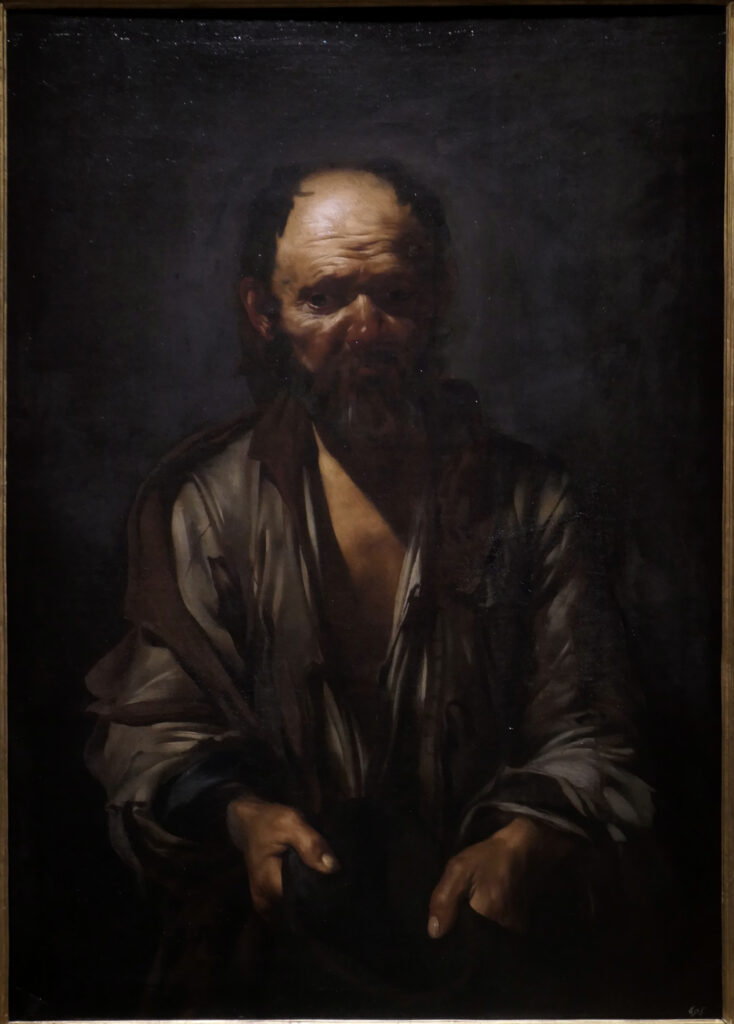

[4]

[4]oil on canvas, 43.3 x 30.7 in. [110 x 78 cm]).

Galleria Borghese, Rome. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Roughly in chronological order, the exhibition began with the room “Ribera in Rome,” initiating novices into the young artist’s accomplished paintings of single, three-quarter-length figures in raking light representing beggar philosophers and the five senses, posed behind tables with relevant attributes. Among them and indicative of the scope of the loans was the Galleria Borghese’s Mendicant (ca. 1612, Fig. 4), firmly attributed to Ribera’s time in Rome, and the stand-out painting in this gallery, the Abelló Collection’s Allegory of Smell (ca. 1615-1616, Fig. 5).

[5]

[5]oil on canvas, 45.1 x 34.8 in. [114.5 x 88.3 cm]).

Abelló Collection, Madrid. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

In that aromatic image, a rugged man dressed in perfectly tattered attire stands behind a table on which rest an onion, knob of garlic and sprig of orange blossom. He holds up a halved onion for the viewer’s contemplation, his appearance suggesting an equally pungent odor.

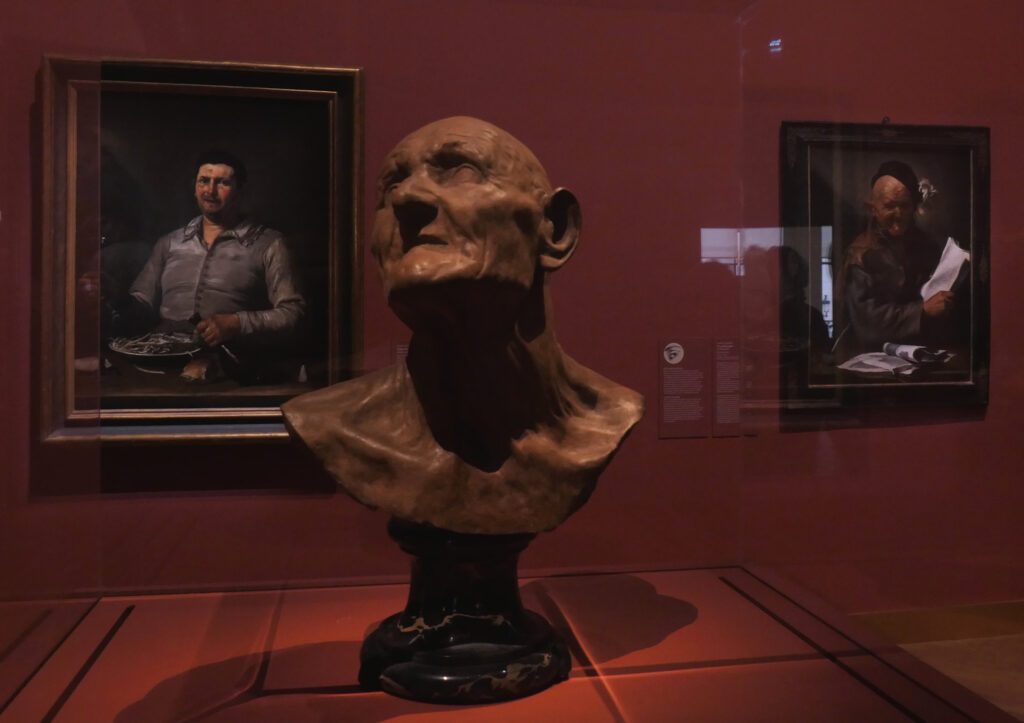

[6]

[6]20.1 x 13.4 x 6.7 in. [51 x 34 x 17 cm]). VIVE – Vittoriano e Palazzo Venezia,

Rome. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Fitting company for Ribera’s character types, Guido Reni’s terracotta Head of an Old Man (Seneca?) (1600-1603, Fig. 6) connected the artist from Játiva with the older, successful painter working in Rome and using the same model.

[7]

[7]oil on canvas, 49.6 x 38.2 in. [126 x 97 cm]). Fondazione di

Studi Roberto Longhi, Florence. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Two more rooms cover lo Spagnoletto’s time in the Eternal City. In “Finding his Place,” a series of three-quarter-length saints and apostles mix together questionable attributions with more secure ones. In the absence of documentation and/or signatures, paintings done prior to Ribera’s move to Naples have been grouped together based on style and subject matter, parameters dependent on the vagaries of connoisseurship. The prize in that room goes to the Saint Bartholomew (ca. 1610-1612, Fig. 7), which takes the holy man’s facial features from Reni’s sculpture and those of the flayed skin from Michelangelo’s portrait, which lo Spagnoletto could have seen in the Farnese Palazzo while in Rome.3

[8]

[8]oil on canvas, 60.2 x 79.1 in. [153 x 201 cm]). Galleria Borghese, Rome.

Photo © 2024, D. Feller.

Controversy emerges in “Ribera Unmasked,” where early multi-figure compositions raise questions about authenticity. In and out of Ribera’s oeuvre, The Judgment of Solomon (ca. 1609, Fig. 8) seems more like a compilation of the greatest hits of other painters rather than an original work by the master. The executioner about to halve the surviving baby stepped out of Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Matthew (1600) with minor changes, the foreshortened hand of the distraught mother mimics hands in the same painter’s Supper at Emmaus (1601), and the dead baby references one in The Massacre of the Innocents by Guido Reni (1611).

[9]

[9](ca. 1610-1612, oil on canvas, 49.6 x 38.2 in. [126 x 97 cm]).

Fondazione di Studi Roberto Longhi, Florence.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Additionally, the figure in the right foreground copies almost exactly the drapery, hands and head of Ribera’s Saint Jude Thaddeus (ca. 1610-1612, Fig. 8), also in the show, the sign of a copyist not an artist repeating himself.

[10]

[10]74 x 106.3 in. [188 x 270]). Museés de Langres, Langres. Photo © Sylvain Riandet

– Ville de Langres.

Finally, a glance around the room at the other large multi-figure paintings like Christ Among the Doctors (ca. 1615, Fig. 10) reveals canvases with figures crowded together, not isolated like in The Judgment of Solomon.

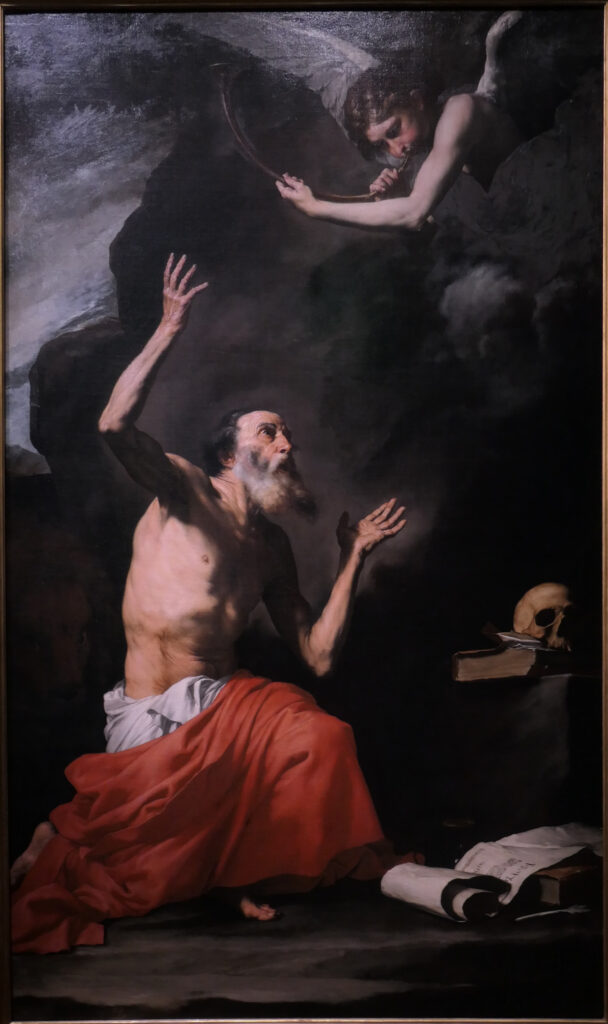

[11]

[11](1626, oil on canvas, 103.2 x 64.6 in. [262 x 164 cm]).

Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

The final word on quite a few other paintings has yet to be written but visitors were given conclusive descriptions of so-so and even subpar paintings, a strategy that dilutes Ribera’s greatness. Nonetheless, the walls were covered with enough brilliant paintings, prints and drawings to leave a highly positive impression on those unfamiliar with him and his work, especially in the subsequent rooms that began with “Ribera to Naples.” After the map and timeline there, the large Saint Jerome and the Angel of Judgment (1626, Fig. 11) from the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte signaled lo Spagnoletto’s predilection for the barrel chest and elongated arms of the old man with wrinkled skin who stars in many of his pictures. Besides that distinctive anatomy, the still-life in the lower right of skull, books, scroll and quill highlights the artist’s special skill at observing, and capturing on canvas, objects in nature. Noteworthy, too, when writing appears in Ribera’s paintings, most of the letters have been painstakingly brushed. Only occasionally do large areas of grey substitute for lines of text.

[12]

[12](ca. 1630, oil on canvas, 48.2 x 39.6 in. [122.5 x 100.5]).

Colomer Collection, Madrid. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

[13]

[13](ca. 1630, oil on canvas, 48.2 x 39.6 in. [122.5 x 100.5]).

Detail. Colomer Collection, Madrid. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Joining the Capodimonte Saint Jerome, a somewhat later and not as finely rendered painting, David with the Head of Goliath (ca. 1630, Fig. 12) from the Colomer Collection, retains a frame from the early days of Ribera scholarship, when the dates of the artist’s birth and death were misunderstood as 1588 to 1656 (Fig. 13). Since then, document discoveries have fleshed out the formerly skeletal narrative of Ribera’s life, and new attributions have transformed the myth of a painter of bloody martyrdoms into a story about a multi-talented artist practiced in all genres, as the rest of the exhibition demonstrated.

[14]

[14]“The Bearded Woman” (1631, oil on canvas, 77.2 x 50 in. [196 x 127 cm]).

Fundación Casa Ducal de Medinaceli, on deposit at the Museo del Prado,

Madrid. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Subjects so far seen left visitors unprepared for the scene that confronted them when they stepped into the next room, “Humble Splendor.” There they met Magdalena Ventura and Her Husband or “The Bearded Woman” (1631, Fig. 14), a masterpiece of naturalism. With exquisite attention to detail, lo Spagnoletto crafted a curious arrangement of a masculine, bearded person in a woman’s garments, with an uncovered spherical breast, holding an infant whose mouth approaches the offered nipple. A man with his hat in his hand stands behind the angry looking mother whose femininity is emphasized by the spindle and distaff resting on a stele that explains the subject as “a great miracle of nature” and the artist as a “modern Apelles of his day” who created the work for the Duke of Alcalá “in wonderful fashion from life.”4 The patron Alcalá collected oddities to arrange in his palace in Seville, Spain, and as viceroy of Naples, gave lo Spagnoletto a studio in the Royal Palace where he could show off his artist, his unusual models, and the painting in progress.

[15]

[15]oil on canvas, 65 x 36 in. [164 x 92 cm]).

Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Once in Naples, the exhibition shifted into themes and subjects, retaining some chronological order, which gave scholars the means to make more comparisons among various paintings, and provided opportunities for new audiences to appreciate Ribera’s thematic and stylistic range. In “A Tribute to the Everyday,” a room filled with genre paintings, The Clubfooted Boy (1642, Fig. 15) drew focus. In a testament to lo Spagnoletto’s knowledge of anatomical anomalies, a boy with a malformed foot clutches a satchel and carries his staff like a rifle as he grins warmly at the viewer, flashing a note requesting alms “for the love of God.” The low horizon, which silhouettes the dark-brown of the child’s clothing against a light sky, reappears in many of Ribera’s drawings and some other paintings.

[16]

[16]red chalk and brush, and red wash on beige paper,

6.3 x 11 in. [159 x 279 mm]). The Metropolitan

Museum of Art, New York. Public domain.

[17]

[17](ca. 1624-1626, pen and brown ink on off-white paper,

11.7 x 6.6 in. [144 x 168 mm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

New York. Public domain.

Interrupting the procession of works on canvas, on the walls of the rooms titled “A Whimsical Illustrator” and “A Skilled Engraver,” drawings generously loaned and prints belonging to the Petit Palais highlighted Ribera’s facility with ink, wash and etching needle. The Metropolitan Museum of Art temporarily parted with two of its gems, A Bat and two Ears (ca. 1626?, Fig. 16) and Study for a Crucifixion of Saint Peter (ca. 1624-1626. Fig. 17). The first exemplifies lo Spagnoletto’s winning ways with red chalk as well as his ever-engaging graphical puzzles.

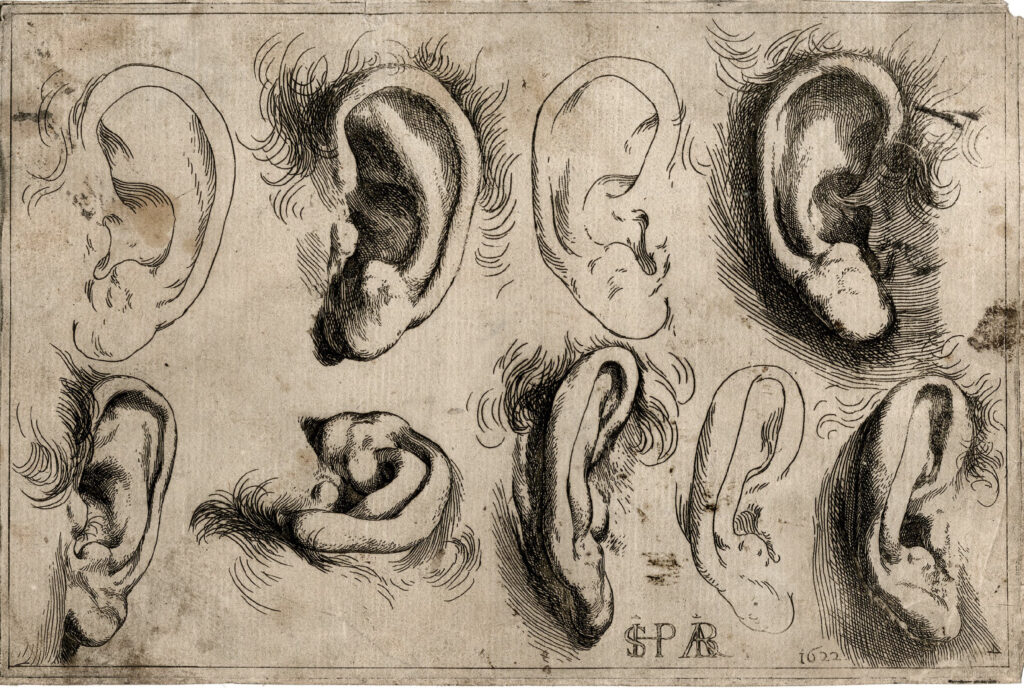

[18]

[18]etching, 5.5 x 8.5 in. [140 x 216 mm]. British Museum,

London. © Trustees of the British Museum.

The motto that the bat grasps in its claws proclaims “shines always virtue” and the ears hark back to Ribera’s educational print of that feature, Studies of Ears (1622, Fig. 18). On the sheet with Saint Peter, multiple lines defining the legs indicate a struggle to get them right and the empty area where the martyr’s left arm should be awaits inclusion of one of the executioners. At the bottom of the sheet, Ribera exercised his quill and whimsy by practicing his signature and turning pen trials into a scorpion.

[19]

[19]72.8 x 90.2 in. [185 x 229 cm]). Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Playfulness permeates many of the master’s pieces, noticeable in the Drunken Silenus (1626, Fig. 19) displayed in the room “Reinventing the Antique Fable.” The mythological subject prompted Ribera to go beyond the usual by depicting Silenus with the swollen belly of cirrhosis, a liver disease caused by excessive alcohol intake. Life-threatening illness notwithstanding, the wine still flows, a donkey brays and a seated young satyr gives the onlooker a mischievous smile. In the lower left, the artist’s signature card is torn apart by a snake, perhaps a reference to envious rivals.

[20]

[20]71.6 x 91.3 in. [182 x 232 cm]). Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte,

Naples. Photo © 2022 D. Feller.

Far more serious, overpowering everything else in the room, the much traveled Apollo Flaying Marsyas (1637, Fig. 20) compelled attention with its dynamic composition, shimmering color and spectrum of emotional expression. Wielding a versatile palette, lo Spagnoletto mixed bright colors with contrasting light and dark values to enliven the canvas.

[21]

[21]50 x 106 in. [127 x 269 cm]). Casa de Alba Collection at Palacio de Monterrey,

Salamanca. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Equally colorful and bright with dark accents, albeit far cheerier than a flaying, Landscape with a Fortress (1639, Fig. 21) faced its same-size partner Landscape with Shepherds in a room of their own, both brought from the Salamanca Palacio de Monterrey, now part of the Fundación Casa de Alba. The two-tiered castle and oddly shaped rock formation capture Ribera’s memories of Játiva, where el Castillo [the Castle] can still be seen from the streets of the once powerful city, and a mountain called el Pueyo [Puig] juts out of otherwise flat terrain. Released from their confinement in the Salamanca palace, the two landscapes could be examined very closely, revealing tiny details of men working on the shores and in boats.

[22]

[22]61.8 x 82.7 in. [157 x 210 cm]). Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Continuing the thematic approach, the room of “Depicting Pathos” brought together three scenes of grief, the best of which was the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza’s Interment of Christ (1633, Fig. 21). In it, the lifeless body of Christ receives tender care from Mary Magdalen who kisses her beloved’s lacerated foot, and from John the Evangelist who looks at her as he cradles his friend’s upper body. Between the other two mourners, the Virgin with clasped hands tearfully prays to some unseen God. Several years later, Ribera would reprise the sorrowful tableau for the Treasury of the Certosa di San Martino, foreshortening Christ’s body to fit into a vertical space. The unsigned Lamentation (1620-1623) from the National Gallery appears to be a copy of the Thyssen-Bornemisza’s Interment despite its earlier date and the Lamentation (ca. 1614-1624) from the Louvre has the condensed crowd of characters associated with lo Spagnoletto’s early multi-figure canvases.

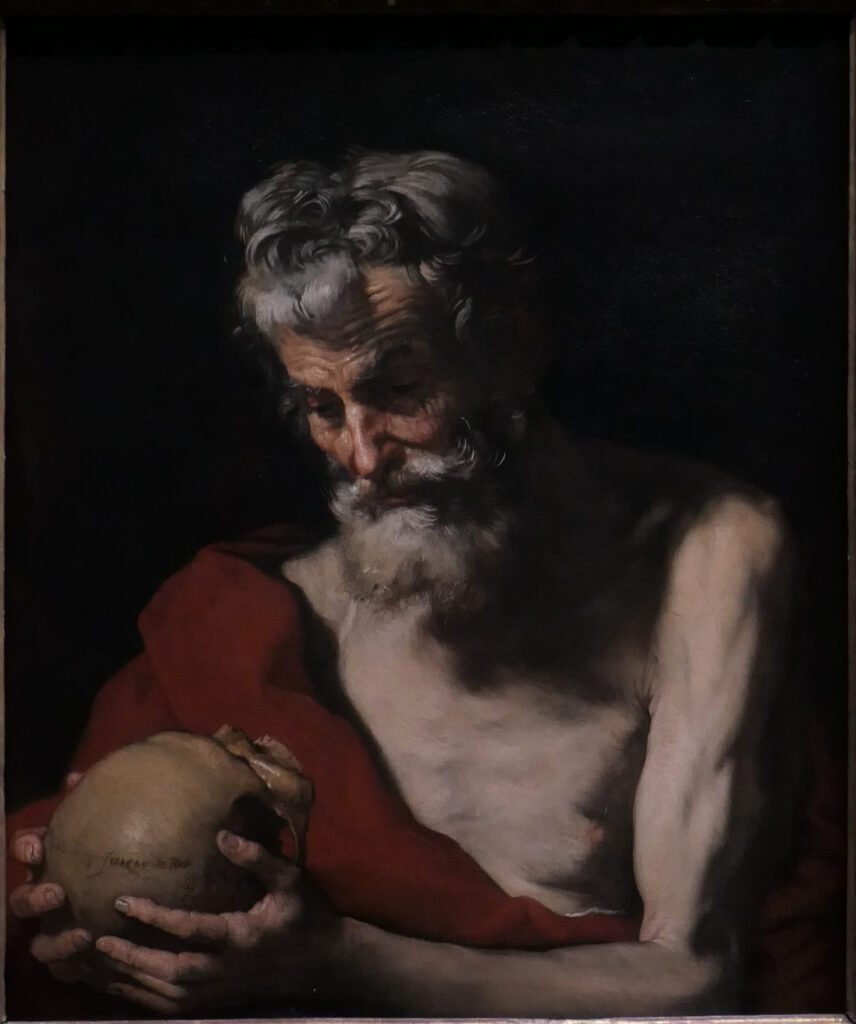

[23]

[23]30.7 x 25.6 in. [78 x 65 cm]). Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

[24]

[24]30.7 x 25.6 in. [78 x 65 cm]). Detail of skull.

Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Building on the previous theme, the room called “Persuasive Power of Truth and Emotion” brought together paintings designed to elicit reverence. In one, Saint Jerome (1643, Fig. 23) contemplates a skull he holds in his hands across which witty Ribera signed his name in place of the coronal suture (Fig. 24) and inscribed the date on the right zygomatic (cheek) bone, asserting unquestionable ownership of the composition.

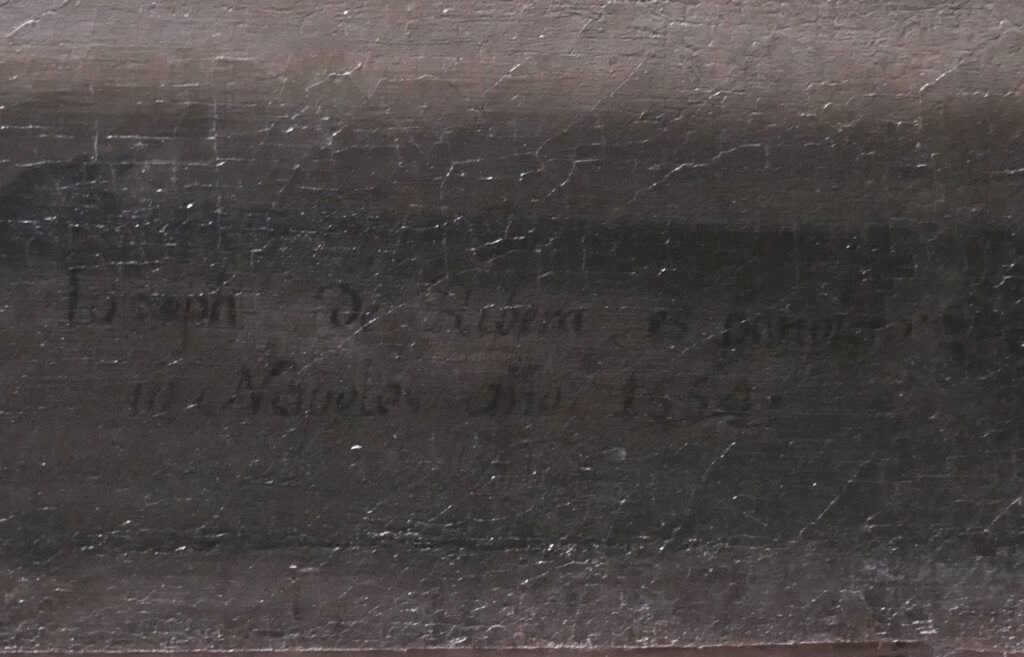

[25]

[25](1652?, oil on canvas, [191 x 155 cm]). Musée de Picardie, Amiens.

Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

[26]

[26](1652?, oil on canvas, [191 x 155 cm]). Detail of signature.

Musée de Picardie, Amiens. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Not so definite is the signature of what has been considered lo Spagnoletto’s last painting, The Miracle of Saint Donato d’Arezzo (1652?, Fig. 25). The proposal that the painting had its start much earlier in his life could explain stylistic elements like the diagonal background light but it can’t account for the highly uncharacteristic signature attached to it.5 No other Ribera signatures read “in Napoles año” and the date is clearly 1654, not 1652. Quite possibly, the painting was rescued from the master’s studio and signed by a misinformed Spaniard well after Ribera’s death in 1652.

[27]

[27]Ribera: Ténèbres et Lumière, Petit Palais, Paris. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Having been introduced to a variety of genres and styles in Ribera’s oeuvre, visitors entered a dark room with deep blue walls and images showcasing a “Spectacle of Violence” (Fig. 27), subject matter on which the artist’s post-mortem reputation had previously been based.

[28]

[28](late 1630s, pen and brown ink with wash, 5.4 x 10.6 in. [136 x 269 mm]).

Teylers Museum, Haarlem. Photo © 2022 D. Feller.

Displayed with several other drawings unrelated to any finished works, Scene of Torture with a Man raising an Axe (late 1630s, Fig. 28) exemplifies lo Spagnoletto’s virtuosity with pen and ink. Combining the torture technique of stretching with the bloody execution method of quartering, the event pictured reflects the artist’s recollections of violence witnessed, or learned from various sources. The robed and hooded confraternity brothers attending to the soul of the soon to be departed victim mark the scene as one of execution not torture.

[29]

[29]Petit Palais, Paris. Photo © 2024 D. Feller.

Continuing into another darkened space (Fig. 29), visitors found scenes of torturous execution seldom if ever exhibited together, a golden opportunity for scholars to closely examine these canvases in relationship to each other. In the large ones, lo Spagnoletto presented scrawny male bodies with barrel chests and elongated sometimes outstretched arms, posing them to maximize exposure of their mostly wrinkled bare flesh and his adept brushwork.

[30]

[30][125 x 100 cm]). Museo di San Martino, Naples.

Photo © 2021 D. Feller.

In a smaller work, from the Museo di San Martino in Naples, executed the year before Ribera died, the artist portrayed Saint Sebastian (1651, Fig. 30) as an all-too-real young man tied to a tree, one arm raised above his head. An arrow draws blood where it pierced a muscle between the rib cage and pelvic crest, and red-rimmed, wide-open eyes look toward heaven. A line of naturalistically rendered body hair runs down the center of the abdomen, meeting a shadow suggestive of pubic hair near the top of the loin cloth. In depictions of Saint Sebastian, artists often took up the challenge of portraying a well-built nude male for the gaze of whomever, to show off their knowledge of anatomy. In his painting, lo Spagnoletto gave the viewer a three-quarter-length youth with a torso alive with muscles, bones, skin, and body hair, extraordinarily sensual and tactile.

After suffering several years of debilitating illness that limited his capacity to paint, Ribera managed to pick up his brushes in the late 1640s to finish a major commission for the Certosa di San Martino and create several single-figure compositions of saints. He became seriously ill before the summer of 1652 and by November had died. Celebrated for quite a while after that, in more recent times his name had lost its recognition power. A three-city exhibition in 1992 temporarily revived his reputation and a generation later, the Petit Palais’s Ribera Ténèbres et Lumière brought before a new audience and old friends many paintings, drawings and prints seldom seen together. Perhaps with this latest retrospective, the name of Jusepe/José de Ribera, called lo Spagnoletto, will join the other ones that always elicit a knowing nod.

_________________________

1. Annick Lemoine and Maïté Metz, “Ribera révélé,” in Ribera Ténèbres et Lumière (Paris: Petit Palais Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, 2024), p. 15.

2. Deborah Feller, “Jusepe/José de Ribera in the Kingdom of Valencia and the workshop of Juan Sariñena: The formation of an artist.” Boletín del Museo del Prado, 2024, number 60.

3. For the provenance of the portrait, see The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564), Attributed to Daniele da Volterra, Italian, probably ca. 1545,” accessed December 17, 2024, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/ collection/search/436771.

4. For the full translation, see Michael Scholz-Hänsel, Jusepe de Ribera: 1591-1652, translated by Paul Aston (Cologne: Könemann Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, 2000), p. 58. Apelles was a highly regarded fourth-century-BCE Greek painter working in the court of Alexander the Great.

5. Pierre Stépanoff, “cat. 58. Le Miracle de saint Donat d’Arezzo,” in Lemoine and Metz, eds. Ribera Ténèbres et Lumière (2024), p. 216.

6. For a table of Ribera’s signatures, see Deborah Feller, “Appendix I: Signatures on Paintings by Jusepe de Ribera,” in Traces of Trauma in the Drawings of Jusepe de Ribera, unpublished manuscript (2024), pp. 418-425.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Ribera Ténèbres et Lumière [Darkness and Light]

November 5, 2024 to February 23, 2025

Petit Palais

Avenue Winston Churchill

75008 Paris

+33 01 53 43 40 0

https://www.petitpalais.paris.fr/en/expositions/ribera