Franz Xaver Messerschmidt:

Sculptor of Pain

Many years ago in a mountain town in what is now Germany, a ten-year-old boy’s father dies and within months the child finds himself in an unfamiliar and urban environment after his mother moves the family to Munich to live with her brother. Soon after, the boy becomes an apprentice in his uncle’s sculpture studio. Years later as an accomplished portraitist, he produces over the course of 12 years a series of unusual heads that remain in his studio until after his premature death at age 47.

Historical records provide little additional early biographical data on Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, the subject of that story and of an exhibit at the Neue Galerie, beyond those directly relevant to his artistic development. Born in 1736, by age 23 he had secured commissions from the royal family in Vienna, where he had moved six years before to study at the Academy of Fine Arts.

Hints of emotional instability surface by 1770, the year Messerschmidt’s financial success enables him to purchase a house in the suburbs. Coincidentally, that year also sees the death of his patron of 15 years, the artist Martin van Meytens (1695-1770). By 1771, at age 35, the sculptor’s life has unraveled.

Commissions have slowed to a trickle and the support he’s enjoyed as acting professor at the Academy evaporates. In 1774, when the Academy’s professor of sculpture dies, Messerschmidt–long considered his natural successor–finds advancement barred. The professors’ committee seizes this opportunity to free themselves of a man whose “…reason occasionally seemed subject to madness.”1 Further along the decision-making ladder, the State Chancellor reports that the artist is “not suitable for [the position]…because for the past three years he had demonstrated ‘some mental confusion’ and suffered occasionally from an ‘unhealthy imagination.’”2

During this period of time, in an attempt to prevail over his demons, Messerschmidt begins work on what will later be called–for lack of better understanding–“character heads,” sculptures depicting extreme facial expressions. His artistic talent and ability never desert him, as evident in the exquisite 1773-74? portrait of Prince Joseph Wezzel of Liechtenstein.

In 1775, Messerschmidt attempts to relocate. He fails to find room at his childhood home, tries Munich for several years, then in August 1777, finds a place to live and work in Bratislava (now part of Slovakia) with his younger brother, also a sculptor. Within three years he has purchased his own home outside the city, where a brief illness thought to be pneumonia, ends his life in 1783.

The Neue Galerie’s exhibition, Franz Xaver Messerschmidt 1736-1783: From Neoclassicism to Expressionism, showcases both the skill and eccentricity of this artist. Greeting the viewer at the entrance to the show, an oval screen mounted behind a drawn picture frame, part of an ornately decorated wall, runs a video showing the “character heads” morphing one into another, looking for all the world like the sculptor posing in front of his mirror.

The first gallery presents work from Messerschmidt’s Early Years in a spacious room with white walls covered with outlines of Baroque paneling and intricate scroll work. Occupying a vitrine in the center of the mostly empty space, six portrait heads dating from as early as 1769, but also as late as 1782, establish the skill with which the sculptor captured images in marble and metal, and perhaps also the soundness of his mind.

Standing on its own in a corner, the portrait of Prince Joseph Wezzel of Liechtenstein, like the uncaged sculptures in later rooms, draws immediate attention by the power of its achievement. Metal becomes flesh and hair, bringing to life one of Messerschmidt’s first patrons.

In the second gallery, the viewer meets the artist transformed. A chorus line of seven heads in a long vitrine kicks off the intriguing subject of Messerschmidt’s Character Heads, his motivation for creating them, and his mental state at the time.

The impossibility of knowing the exact etiology and nature of the sculptor’s breakdown has not deterred the propagation of hypotheses, beginning with Friedrich Nicolai’s account of his 1781 visit to the artist’s studio. In a skeptical and condescending tone, Nicolai made observations and shared what he managed to extract from the reticent Messerschmidt.

He learned that spirits “frightened and plagued [the sculptor] at night,” pursuing him despite his having “lived so chastely.”3 Following a convoluted line of reasoning that Nicola valiantly attempted to record and explain, Messerschmidt arrived at the belief that “the Spirit of Proportion was envious of him because he came so close to perfecting his knowledge of proportions and for this reason caused him those pains [in his belly and thighs].”4

Further, the artist imagined that “if he pinched himself in various parts of his body, especially on his right side amid the ribs, and linked this with a grimace on his face which would have the same Egyptian proportion required in each instance with the pinching of the rib flesh, the height of perfection would be attained” and therefore protect him from the spirits.5

Nicolai came to his own conclusions about what ailed Messerschmidt as did Ernst Kris centuries later in his 1932 book on the sculptor, elements of which appeared in the 1952 English translation of his Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art.6 Each naturally brought to the endeavor his own point of view, not unlike the blind men and the elephant. Nicolai embedded his assessment in the rational thinking of his Age of Enlightenment and Kris wrote in the psychosexual language of Freudian theory.

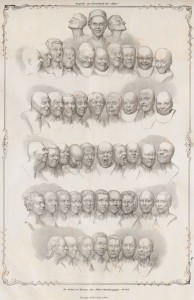

The “character heads”—the best place to start in any analysis of Messerschmidt—tell their own story, speaking volumes about him. Unfortunately, because no one has yet found a way to date them, they can’t be used to track the evolution of his condition. Nor has anyone had the courage to alter the misleading and sometimes comical names given them after Messerschmidt’s death.

As a group, the “character heads” suggest a person in great distress. Although Messerschmidt referenced his own mirror image, only some approach self portraiture, the rest depict types. Most of the sculptures have eyes shut so firmly that folds and wrinkles accrue around them. The ones with wide open eyes stare blankly at nothing in particular, an effect enhanced by the absence of pupils. A few open their mouths but the majority close them tightly, hiding their lips. By way of explanation, Messerschmidt pointed out to Nicolai that “men must simply pull in the red of the lips entirely because no animal shows it.”7

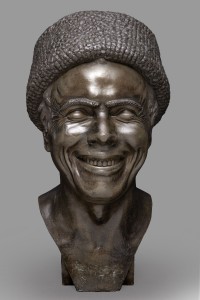

Messerschmidt’s suffering suffuses all his “character heads” including The Artist as He Imagined Himself Laughing. Closely resembling its creator, this sculpture presents a man in a lamb’s wool hat with a mouth open wide enough to show the top row of his teeth. As expected in any heartfelt grin, the action of the muscles that pull back the corners of the mouth push up the lower lids to cover the bottom of the eyes.8 That they come almost halfway up the eye belies the expression’s authenticity and provides evidence of the sculptor’s striking the pose for other than representational purposes, perhaps to openly challenge his demons.

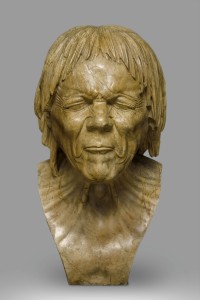

Anything but happy, The Difficult Secret expresses Messerschmidt’s pain in its eyes, where the action of the muscle raising the inner portion of the left brow pulls up the inner corner of the left upper lid.8 The downturned corners of the mouth, usually associated with disgust,9 coupled with the clenched lips, give the impression of grim determination. Each sculpture portrays Messerschmidt’s relentless battle to repel the evil spirits haunting him.

Possessing one of the sillier names, A Hypocrite and Slanderer departs from the typical upright or slightly lifted head positions by tilting downward, requiring viewers to get on their knees for a complete view, raising the question of Messerschmidt’s own position while creating it. With the head retracting into the chest/body/self, this sculpture poignantly expresses the sculptor’s shame.

Messerschmidt could have unconsciously projected onto imagined evil spirits those impulses and emotions that his psyche found intolerable. Young children who lose a parent often blame themselves for the loss, remembering times when in a fit of frustration at a request denied, they wished their parents dead. For a child, the loss of a parent equates with abandonment and leads to diminished self-worth; after all, parents don’t leave good children. Without help, these children grow up harboring unanswered questions about early parental loss, and doubts about their own role in their parent’s death.

From age 19, Messerschmidt benefited from a relationship with the much older van Meytens, his early patron, perhaps more than just artistically and professionally. The 15-year bond with van Meytens provided an opportunity for the artist to receive care and attention from a father figure but might also have stirred up fears based on unconscious shame, guilt and rage from the long ago death of his father. In addition, the natural competition between student and teacher might have contributed to Messerschmidt’s projection of jealousy onto his demons following the man’s death, a manifestation of his guilt over seeking to best his mentor. Finally, consideration must be given to the possibility that the relationship with van Meytens had a sexual component, which would explain Messerschmidt’s lack of interest in women and his sexual conflicts.

When van Meytens died in 1770, Messerschmidt found himself awash in that little boy’s emotional turmoil. Adults who re-experience child feelings usually fear for their sanity because of the visceral and non-adult-like intensity of them. To preserve his ego, Messerschmidt regrouped by blaming his reactions on jealous demons who pursued him. Paranoid feelings can indicate projected guilt. When the paranoia overflowed into his work situation, the Academy had to get rid of him. Once again he found himself abandoned.

In two carved alabaster sculptures, Just Rescued from Drowning and The Vexed Man, Messerschmidt demonstrates his expert handling of the soft stone, incising impossible wrinkles to suggest aged skin and to emphasize the expression. With pursed lips, scrunched up noses, shut eyes and heads pitched forward, these old men anticipate imminent contact with something distinctly unpleasant. They brace for it and at the same time seem resigned to its inevitability.

At first glance, The Yawner seems to be screaming, but a mouth that opens by lowering the chin into the chest impedes the flow of air in and out of the lungs, opposite of the maximum exhalation required for a scream. As for the work’s title, Darwin had this to say about yawning: “[It] commences with a deep inspiration, followed by a long and forcible expiration,”10 not possible under these circumstances. The vulnerability of the open mouth contrasts with the avoidance of the retracted tongue, squinting eyes, and nose wrinkled in disgust, indicating ambivalence–or more painfully, conflict–about the situation.

The title bestowed by the anonymous author who originally named the “character heads” comes closest to accuracy in Quiet Peaceful Sleep. Here Messerschmidt has captured in a face devoid of the usual abundance of wrinkles an expression of peaceful resignation. Gently lowered upper lids close the eyes under a minimally knitted brow. The nose sits neutrally over a mouth that betrays some tension in its thinned upper lip, which rests on a full lower one. The expression brings to mind the state of the suicide shortly before an attempt, when despair has lifted enough to liberate energy for action; a calm descends on the victim who looks forward to final release/relief from pain.

For a full comprehension of Messerschmidt’s struggles, notice must be paid to the sculptures with bands across their mouths. If the tightly pressed and retracted lips in the rest of the heads fail to impress with their need to keep something in (or out), then slapping a strip across the mouth surely clarifies that intention.

Messerschmidt must have feared the power of his mouth to give voice to the taboo feelings he carried and perhaps also to divulge the true nature of his relationship with his early patron. Wrestling against that force, he left behind for posterity to ponder, beautifully crafted alabaster and metal portraits that continue to keep his secrets.

______________________________

1 Maria Pötzl-Malikova in Franz Xaver Messserschmidt 1736–1783, 21.

2 Ibid.

3 Frederich Nicolai, “Description of a Journey through Germany and Switzerland in the Year 1781, in Franz Xaver Messserschmidt 1736–1783, 208.

4 Ibid, 209.

5 Ibid.

6 Ernst Kris, Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art, 1971, 128.

7 Op cit.

8 Paul Ekman and Wallace V. Friesen, Unmasking the Face: A Guide to Recognizing Emotions from Facial Expressions, 1975, 104–5.

9 Ibid, 117–119.

10 Charles Darwin, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, [1872], 1989. 165.

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt 1736-1783:

from Neoclassicism to Expressionism

Neue Galerie

1048 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10028

(212)628-6200

Catalog available.

![Plate 18, The Difficult Secret [Front] for site](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Plate-18-The-Difficult-Secret-Front-for-site-217x300.jpg)