News & Views

Print This Post Print This Post

June 30th, 2015

All That Glitters…

Art Museums Making It Art

I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description, and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it…1

When Justice Potter Stewart penned those word in a 1964 concurring opinion on a case involving a motion picture, he had in mind pornography. Today the statement could easily apply to a certain attitude held by many people toward art, unaware as they are of the vulnerability to manipulation of their belief.

Attempting to define the “kinds of material embraced within that shorthand description” art has been a favorite pastime of deep thinkers from at least as far back as Plato, with neuroscientists recently adding their voices to the cacophony.2 When creative types stepped outside accepted norms (as they are wont to do), they further complicated this age-old struggle to determine the nature of art.

The terminology problem achieved critical mass when in April 1917 Marcel Duchamp–pushing the limits of the Society of Independent Artists’ policy of accepting all proffered objects–presented to its hanging committee a urinal he purchased from the J. L. Mott Iron Works company, having affixed to it the signature “R. Mutt” and anointed it Fountain.3 In another sphere of activity but also during the early part of the twentieth century, a boom in archaeological digs coupled with a proliferation of publications for a general audience introduced yet another set of objects for consideration as art.4 Contemporaneously, indigenous works from Africa began to migrate from ethnic collections to art galleries,5 setting in motion a reevaluation of comparable items brought from analogous cultures elsewhere.

The legacy of these developments can be found today gracing the interiors of art museums, where (among other factors) a simple change in accompanying label can alter the meaning of an object on display.6

![Theaster Gates, In Case of Race Riot II (2011, wood, metal and hoses, 32 x 25 x 6 in [81.3 x 63.5 x 15.2 cm]). Brooklyn Museum, New York.](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/T-Gates-In-Case-of-Race-Riot-II-237x300.jpg) Theaster Gates, In Case of Race Riot II (2011, wood, metal and hoses, 32 x 25 x 6 in [81.3 x 63.5 x 15.2 cm]). Brooklyn Museum, New York. Tucked away in a corner in the American Identities galleries of the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York on the wall of a section headed “Everyday Life/A Nation Divided,” behind a framed sheet of glass, a length of coiled hose invites associations with its primary purpose of extinguishing fires. One could be forgiven for expecting the accompanying wall text to announce, “In case of fire, break glass.”

Instead, the explanatory label begins with a name–Theaster Gates, adds a title–In Case of Race Riot II, and includes a list of materials used in its assemblage. The story of the piece follows. The viewer is cued to consider the object a work of art by the box that frames it, the label that describes it, the spotlighting that illuminates it, and the art museum that placed it in the company of other similarly designated pieces. The power of this image to evoke an emotional response in beholders is enhanced by any personal recollections of the civil rights events of the 1960s to which it refers. Such reminiscences are encouraged by the declared theme of the gallery, “A Nation Divided.”

Clearly art museums do far more than simply collect and display artwork. These structures have been variously described as: ritual spaces ”designed to induce in viewers an intense absorption with artistic spirits of the past;”7 “philosophical instruments” that “propose taxonomies of the world” and “encourage aesthetic engagement with their contents,”8 “optical instrument[s] for the refracting of society;”9 places for the “staging of objects relative to other objects in a plotting system that transforms juxtaposition and simple succession into an evolutionary narrative of influence and descent…a configured story culminating in our present;”10 guarantors of the “artificial longevity” of ultimately perishable commodities,11 which attempt to “contradict the irreversibility of time and its end result in death;”12 and–most relevant to this exploration–an institution with the purpose of teaching “the difference between pencils and works of art”13 or more generally, “works of art and mere real things.”14

![Marcel Duchamp, In Advance of the Broken Arm (1964 [prototype, 1915], wood and galvanized-iron snow shovel, 52 in [132 cm] high). Museum of Modern Art, New York.](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Duchamp-Snow-Shovel-225x300.jpg) Marcel Duchamp, In Advance of the Broken Arm (1964 [prototype, 1915], wood and galvanized-iron snow shovel, 52 in [132 cm] high). Museum of Modern Art, New York. Enter Marcel Duchamp with his readymades and insistence that “‘[a]n ordinary object’ can be ‘elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist,’” 15 which is to say that intention trumps all. Of course, minus the hallowed halls of art museums and related gallery spaces such pieces would lose the foils so essential to their argument. 16

The heights of absurdity possible when artists (or art museums or the art market) become sole arbiters of an object’s artistic status found dramatic expression in 1998 when Alan Alda played Marc, an outraged skeptic in the Broadway production of Art. When Marc’s longtime friend proudly displayed the latest (and very expensive) addition to his modern art collection–a totally white canvas, the ensuing conflict over the nature of art (which included a third pal as intermediary) threatened to derail a fifteen-year friendship.17 Such is the passion invoked by the question, “What is art?”

An alternative way of posing the question–“When is art?”18–underscores the importance of context. One can designate as art a found, constructed, fabricated or handcrafted work, but its definitive determination as such seems to rely on its ultimate resting place. Art museums display art. Natural history museums house ethnographic collections and archaeological finds. Design museums celebrate human’s ingenuity. Large enough encyclopedic museums show it all. Or so it would seem.

The visitor to a Surrealism exhibit, encountering Duchamp’s snow shovel suspended in the museum gallery, can’t see how it differs from the one that leans against the wall in a suburban garage. Titled In Advance of the Broken Arm, the readymade proves that “a thing may function as a work of art at some times and not at others.”19

![Radio Compass Loop Antenna Housing (c. 1940, rag-filled Bakelite and metal, 13¾ x 91/16 x 26⅜ in [35 x 23 x 67 cm]). Smithsonian Design Museum, Cooper Hewitt, New York.](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Radar-Housing-Cooper-Hewitt-300x225.jpg) Radio Compass Loop Antenna Housing (c. 1940, rag-filled Bakelite and metal, 13¾ x 91/16 x 26⅜ in [35 x 23 x 67 cm]). Smithsonian Design Museum, Cooper Hewitt, New York. ![Constantin Brancusi, Sleeping Muse II (c. 1926, polished bronze, 6½ x 7½ x 11½ in [16.5 x 19.1 x 29.2 cm]). Harvard Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts.](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Brancusi-Sleeping-Muse-self-portrait-300x225.jpg) Constantin Brancusi, Sleeping Muse II (c. 1926, polished bronze, 6½ x 7½ x 11½ in [16.5 x 19.1 x 29.2 cm]). Harvard Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts. At the Cooper Hewitt, the Smithsonian’s Design Museum in New York, ensconced in a vitrine (those ubiquitous glass cases that prepare visitors for an art experience), an oblate spheroid tapering to a point at one end, with the appearance of wood but actually composed of “the first entirely synthetic plastic,” 20 rests on a base of metal that functions as a stand. Relocated to the sculpture wing of a modern/contemporary art museum, this Radio Compass Loop Antenna Housing from about 1940 would nestle comfortably up against the Jean Arps and Henry Moores. But even more striking is its formal resemblance to the Constantin Brancusi Sleeping Muse II (c. 1926) that resides in the Harvard Art Museums.

![Henry Dreyfuss, Design for Acratherm Gauge (1943, brush and gouache, graphite, pen and black ink on illustration board, 11 × 8½ in [27.9 × 21.6 cm]). Smithsonian Design Museum, Cooper Hewitt, New York.](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Cooper-Hewitt-Design-for-Acatherm-Gauge-225x300.jpg) Henry Dreyfuss, Design for Acratherm Gauge (1943, brush and gouache, graphite, pen and black ink on illustration board, 11 × 8½ in [27.9 × 21.6 cm]). Smithsonian Design Museum, Cooper Hewitt, New York. This ambiguity is also evident on the first floor of the Cooper Hewitt amid an assemblage of aids to mobility and handling, where a framed gouache drawing by Henry Dreyfuss called Design for Acratherm Gauge presents the observer with a tour de force of trompe l’oeil effect. This picture’s placement in a room with other useful instruments and its clear designation as a product of design attempt unsuccessfully to differentiate it from an artist’s finished work on paper.

![Walter Launt Palmer, Painting, Interior of Henry de Forest House (1878, oil on canvas mounted on canvas, 24⅛ x 18 in [61.3 x 45.7 cm]). Smithsonian Design Museum, Cooper Hewitt, New York.](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Cooper-Hewitt-Painting-Interior-of-de-Forest-House-225x300.jpg) Walter Launt Palmer, Painting, Interior of Henry de Forest House (1878, oil on canvas mounted on canvas, 24⅛ x 18 in [61.3 x 45.7 cm]). Smithsonian Design Museum, Cooper Hewitt, New York.  Label for Walter Launt Palmer, Painting, Interior of Henry de Forest House. Upstairs at the same design museum, great pains have been taken to ensure that visitors don’t mistake a bona fide artwork for an architect’s rendering of a domestic interior. The first word on the label for Walter Launt Palmer’s painting of the Interior of Henry de Forest House (1878) is “painting.”

Displayed on “Tools” floor of Cooper Hewitt. Damián Ortega, Controller of the Universe (2007, found tools and wire, 9⅓ x 13⅓ x 15 ft [2.85 x 4.06 x 4.55 m]). Collection of Glenn and Amanda Fuhrman, New York.  Displayed in art gallery. Damián Ortega, Controller of the Universe (2007, found tools and wire, dimensions vary). Collection of Glenn and Amanda Fuhrman, New York. The Cooper Hewitt is filled with objects harboring this potential for dual identities. A relative of Duchamp’s snow shovel (functional identity)/In Advance of the Broken Arm (art identity) appears in Damián Ortega’s Controller of the Universe (2007) as one element in a starburst of tools through the axis of which visitors can wander. This central attraction of the design museum’s “Tools” floor makes a solo appearance in a room with white walls in a photo posted on the museum’s website.21 Reassembled to fit into an art gallery, this spatially condensed version transforms the viewers’ experience from active participation to passive contemplation of an esteemed work of art.

![Unidentified (French) artist, Salt Cellar with the Episodes from the Life of Hercules and Salt Cellar with Allegorical Scenes (c. 1550, enamel on copper, 2⅞ x 3 in [7.3 x 7.6 cm]). Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts.](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Harvard-Salt-Cellar-Life-of-Hercules-painting-225x300.jpg) Unidentified (French) artist, Salt Cellar with the Episodes from the Life of Hercules and Salt Cellar with Allegorical Scenes (c. 1550, enamel on copper, 2⅞ x 3 in [7.3 x 7.6 cm]). Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Likewise, stepping into the Harvard Art Museums–whose august exterior signals visitors to expect an elevated cultural experience, then ambling through acres of paintings, sculptures and less definable objects, and coming upon a vitrine with an array of utilitarian things of venerable pedigree, one is already well primed to see two attractive French salt cellars from about 1550 as works of art. That impression gets considerable assistance from a painting on the wall immediately behind them–of Martin Luther (1546, from the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder), and an additional boost from an identifying label that calls their maker an “Unidentified artist.”

![Egmont Arons, designer, Meat Slicer (c. 1935, steel, 12½ x 17 x 20½ in [31.8 x 43.2 x 52.1 cm]) and Edo Period, Japan, Pothook Hanger (Jizai-Gake) (18th to 19th century, iron and wood, 18 x 16 x 4½ in [45.7 x 40.6 x 11.4 cm]). Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York.](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Meat-Slicer-and-Hook-BMA-225x300.jpg) Egmont Arons, designer, Meat Slicer (c. 1935, steel, 12½ x 17 x 20½ in [31.8 x 43.2 x 52.1 cm]) and Edo Period, Japan, Pothook Hanger (Jizai-Gake) (18th to 19th century, iron and wood, 18 x 16 x 4½ in [45.7 x 40.6 x 11.4 cm]). Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York. Less clear is the message communicated by the Brooklyn Museum of Art in its “Connecting Cultures” exhibit, a room hosting a hodgepodge of paintings, sculpture, ethnic objects and useful things from across millennia. Putting aside the impossibility of getting close enough to see some of them (placed on shelves that soar above eye level), one confronts a dilemma in a vitrine containing a twentieth-century American-made, shiny steel Meat Slicer and a two-hundred-year-old, dark-hued Edo period iron-and-wood Pothook Hanger (Jizai-Gake).

Visitors might be less inclined to regard the all-too-familiar deli appliance as art and feel similarly about the slicer’s neighbor, the large hook. Situate the much older, exotic Japanese piece in the Asian wing of any art museum, hang it on a wall under spotlighting and affix to the display a typical artwork label, and responses will likely change.

“University Collections Gallery: African Art,” Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Ample evidence of this “museum effect–the tendency to isolate something from its world, to offer it up for attentive looking and thus to transform it into art like our own”22 exists in the University Collections Gallery of African Art at the Harvard Art Museums. There a select group of products from several countries in Africa, sparsely arranged in various shaped glass enclosures, hangs on the walls–a collection small enough in number for a single wall label to comfortably contain descriptions of all the pieces.

Axe, Songya, Democratic Republic of Congo (1914 or earlier, iron, copper and wood). Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts A stunningly beautiful axe, with a wooden handle and complex wrought iron head, shares its glass box frame with a less ornate companion, emitting conflicting messages about its identity. Everything about the setup, especially the segregation of the axes in their own display cases, emphasizes the uniqueness of each piece, connecting it with the art just seen in nearby galleries.

Shown in an exhibit hall at a natural history museum among many other examples of its type, these implements might be classified as artifacts, things that have “primarily the status of tools, of instruments or objects of use.”23 In a more inclusive definition, the dictionary describes them as “object[s] made by a human being, typically…of cultural or historical interest,”24 a category that can range from “sophisticated and culturally valuable artworks..to the smallest everyday thing.”25

The pool of opinion on what qualifies something as art teems with dangerous life forms, but the variables of “complex abstract thinking,”26 embodiment of a thought and expression of meaning,27 and evocation of emotions28 that include aesthetic delight,29 serve to classify most of them. While that last trait is both an unnecessary and insufficient determinant of artistic status, it can easily seduce observers into believing they are in the presence of real art (whatever that might be). Art museums, intentionally or not, often cash in on that response.

With barrier. Ai Weiwei, Untitled (2014, edition of 60, mixed media, primarily stainless steel). Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York. On a wall near the ticket counter at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, a glittery silver city bike hangs behind a barrier, its artist Ai Weiwei having given it the noncommittal tag of Untitled. In the list of materials provided by either him or the museum–“mixed media, primarily stainless steel”30–the word bicycle is conspicuously absence, perhaps in hopes of enticing some unsuspecting bike-riding enthusiast, smitten by the beauty of the artifact glowing before her, to perceive the object as a work of art by world-famous Chinese artist Ai (as the label, lighting, ribbon barrier and placement on an art museum wall encourage) and part with the asking price of $27,500, an amount designed to offset the cost of the artist’s now past exhibition, Ai Weiwei: According to What?

Tooling around the city mounted on this splendid bike might turn it back into a “mere real thing,” diminishing its monetary though not aesthetic value. Hanging it back on a wall would restore its identity as art, the preference of any art collector (or curator). But for the rider, whose delight derives from speeding along on wheels, immobilizing such an exquisitely crafted bicycle would rob it of its raison d’être and, incidentally, extinguish the pleasure of exhibiting a prized possession in an arena markedly different from the interior of any art museum.

__________________________________

1 Justice Potter Stewart, Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184 (1964), p. 197.

2 Anjan Chatterjee, The Aesthetic Brain: How We Evolved to Desire Beauty and Enjoy Art (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

3 Thierry de Duve, “‘This is Art’: Anatomy of a Sentence,” ArtForum, April 2014, 2.

4 Ably demonstrated in From Ancient to Modern: Archaeology and Aesthetics, an exhibition at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, February 12- June 7, 2015.

5 In 1914, Alfred Stieglitz mounted at his Gallery 291 “what he claimed to be the first exhibition anywhere to present African sculpture as fine art rather than ethnography.” See Modern Art and America: Alfred Stieglitz and his New York Galleries, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Accessed March 15, 2015, https://www.nga.gov/ exhibitions/modart_2.shtm.

6 Chatterjee, The Aesthetic Brain, 140.

7 Carol Duncan, “The Art Museum as Ritual,” Art Bulletin LXXVII, no. 1 (March 1995): 12.

8 Ivan Gaskell, “The Riddle of a Riddle,” Contemporary Aesthetics 6 (2008): 7.

9 Donald Preziosi, “Brain of the Earth’s Body: Museums and the Framing of Modernity,” in Museum Studies: An Anthology of Contexts, edited by Bettina Messias Carbonell (Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004), 77.

10 Ibid., 78.

11 Boris Groys, Art Power (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2008), 38.

12 Duncan, 12.

13 E. H. Gombrich, “The Museum: Past, Present and Future,” Critical Inquiry 3, no. 3 (Spring 1977), 465.

14 Arthur C. Danto, “Artifact and Art,” in ART/artifact: African Art in Anthropology Collections (New York: The Center for African Art, 1988), 23.

15 Museum of Modern Art, catalog entry for In Advance of the Broken Arm. Accessed March 17, 2015. http://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/marcel-duchamp-in- advance-of-the-broken-arm-august-1964-fourth-version-after-lost-original-of-november-1915.

16 Groys, “On the New.”

17 “Art (play),” Wikipedia. Accessed March 19, 2015: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Art_(play).

18 Nelson Goodman, Ways of Worldmaking (Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett Publishing Company, 1978), 66.

19 Ibid.

20 Object label, Radio Compass Loop Antenna Housing, Smithsonian Design Museum, Cooper Hewitt, New York.

21 “Controller of the Universe, 2007,” Cooper Hewitt website. Accessed March 19, 2015: https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/35460745/.

22 Svetlana Alpers, “The Museum as a Way of Seeing” in Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, edited by Ivan Karp and Steven D. Lavine (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute, 1991), 27.

23 Google definition. Accessed March 19, 2015: https://www.google.com/ search?q=define:+arbiters+&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8#q=define:+artifact.

24 Danto, “Artifact and Art,” 28.

25 Gaskell, “The Riddle of the Riddle,” 4.

26 Ibid.

27 Danto, “Artifact and Art,” 32.

28 Chatterjee, The Aesthetic Brain, 131.

29 E. H. Gombrich, “The Museum: Past, Present and Future,” 450.

30 Object label, Ai Weiwei, Untitled, Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York.

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post Print This Post

May 12th, 2015

Drawn to Perfection:

Annibale Carracci

Works on Paper

[To view the slide show in a separate tab while reading the text, place the mouse pointer over the first slide, right click, select <This Frame>, then <Open Frame in New Tab>.]

[slide 1: Title]

[slide 2: Self-Portrait [Autoritratto col cappello “a quatre’acque”] (April 17, 1593, oil on canvas, 9½ x 7? in [24 x 20 cm]). Galleria Nazionale, Parma, Italy.]

Legend has it that when Annibale Carracci was a young boy returning to Bologna with his father from a trip to Cremona and they were set upon by robbers, the lad’s precocious ability to render in line what presented itself to his eye aided in the apprehension of the criminals. The youthful Annibale sketched the culprits from memory so accurately that they were easily recognized and brought to justice quickly enough to ensure return of his father’s stolen money.1

While that and other stories that grew up around the famed artistic family of Carracci might well be apocryphal, the existence of these tales of artistic prowess do bear witness to the high regard in which the two brothers and their cousin were held, and in particular to Annibale’s prodigious drawing skills. Born in 1560 in Bologna, the youngest of the triumvirate that included Agostino (his older brother by three years) and their older cousin Ludovico (born in 1555), Annibale was characterized by one of his early biographers as a scruffy, introverted, envious and financially naive prankster.2

Never one to be ashamed of his social standing, Annibale often chided the scholarly, upwardly-striving Agostino–who was far more educated than his younger brother–on the way he hobnobbed with courtiers and the like. To put Agostino in his place, one day in Rome where they were working in the Palazzo Farnese, Annibale handed his pompous brother a letter while they were in the midst of a well-bred group that then eagerly awaited the unveiling of its contents. Much to Agostino’s embarrassment, the opened missive contained a drawing of their parents: father in his spectacles threading a needle and mother holding a pair of scissors,3 a not-so-gentle reminder of the brothers’ humble origins.

For Annibale, drawing trumped speech when it came to personal expression, a stance he made quite clear in another face-off with his loquacious brother who was going on at length about the antique marvels he was discovering after his recent move to Rome to help out at the Farnese. When Agostino made the mistake of taking to task the silent Annibale for not joining in the erudite conversation, accusing him of lacking appreciation for the ancient works, Annibale once again got the better of his older brother with charcoal.

Unbeknownst to Agostino until too late, on a nearby wall Annibale had begun a drawing designed to communicate his reverence for the Roman art he was discovering. When done, he stepped aside to display a perfect rendering from memory of the Laocoön. The onlookers praised the younger artist. Agostino fell silent, and Annibale walked away triumphant–but not before laughingly admonishing his brother, “Poets paint with words; painters speak with works.”4

From very early on, reaching for a drawing implement had been Annibale Carracci’s first impulse and it continued to be throughout his life even into his last few years, when the heavy toll that illness took on his expressive abilities left him unable to do much else. From the pleasurable exercise of sketching his surroundings to the serious study of posed studio models, this master draftsman always looked first to his teacher nature for whatever answers he needed, supplementing it with metaphorical (and sometimes actual) forays into the studios of other artists to draw from their work. Not only did Annibale “speak with [his] works,” he also thought with them–evident in the many surviving pages of preliminary ideas for compositions that he hatched and developed, and often later discarded. Ultimately, these various aspects of his drawing practice would coalesce into a full-size cartoon used for transferring his final design onto wall, canvas or copper plate.

[slide 3: A Man Weighing Meat (c. 1582-83, red chalk on beige paper, 1015/16 x 61/16 in [278 x 170 cm]). Collection Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

The Butcher Shop (1583, oil on canvas, 73 x 105 in [185 × 266 cm]). Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford, UK.]

By the time he drew A Man Weighing Meat (c. 1582-83), the twenty-something-year-old Annibale had already been drawing for many years, but now his interest in depicting everyday life found expression in genre paintings of a type unlike the pastoral idylls of his contemporaries.5 Here he has posed his model, probably a workshop apprentice,6 in the garb of a butcher and given him props–a balance (stadera) for weighing meat along with a stand-in for a slab of flesh–that find their way into The Butcher Shop (1583), one of his earliest known paintings.

The bare-elbow study to the right of the figure in the red-chalk drawing reflects a rethinking of the pose that will appear in the final composition; Annibale angled upward the forearm and rolled back the sleeve. Highlighting the artist’s selection of an expedient rather than exact model, the character of the butcher shop worker in the painting differs from the assistant in the studio; he is older with a neatly trimmed beard, taller stature and somewhat slimmer build. His hat, of a different style, sits back on his head rather than forward as in the drawing.

Early on in the absence of significant commissions for the Carracci shop, genre paintings, like small devotional pictures, provided a quick and relatively easy way for the three young men to churn out work that they could sell on the open market and that would also advertise their skills.7 For Annibale, who had been sketching from life for years, it provided a natural extension of his artistic interests, “demand[ing] little more than a direct and forthright approach to the visual material.”8

[slide 4: A Domestic Scene (1582-1584, pen with brown and gray-black ink, brush with gray and brown wash, over black chalk, 12⅞ x 9¼ in [32.8 x 23.6 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.]

In a very different kind of scene as well as medium, Annibale assembled three figures and a cat around a fire. A young woman, holding a cloth or garment, leans over the flame and looks back toward a young girl, vaguely indicated in line and wash, while a much younger child merges visually with his caretaker’s skirt. A close look at the actual drawing revealed a lack of spontaneity in the manner in which the ink wash was applied, especially in the woman’s skirt, where Annibale–instead of drawing the brush down the form and guiding the pool of diluted ink–seems to have attempted to blend it as he would have done with oil paint, resulting in a somewhat overworked appearance and mild abrasion of the paper. It would not be long before he began to produce far more accomplished ink drawings.

[slide 5: The Virgin and Child Resting Outside a City Gate (n.d., pen and brown ink, brush with traces of brown wash, on light brown beige paper; traces of framing outlines in pen and brown ink, 7⅜ x 8½ in [18.8 x 21.6 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.]

A small, undated compositional sketch of The Virgin and Child Resting Outside a City Gate contrasts in ink handling with the earlier genre scene. Here evenly spaced, parallel hatching designates shadow while sure lines pick out the landscape and architectural features. Schematic rays of the sun–which reappear in a very late pen drawing9–disappear behind horizontal bands of clouds, and figures diminishing in size create a feeling of recession into space. A discreetly contoured area of thinned ink on the shaded side of the Virgin’s head has been applied without any fuss, first a middle-value wash and then a much darker band in the deeper shadow on the periphery of the head–no attempt being made to blend the two. The Virgin’s face, redolent with Correggio sweetness,10 also suggests a date later than the domestic scene.

Not only did Annibale borrow from the output of other artists, he thought deeply about the differences in their styles, forming definite opinions about their work, a fact that runs contrary to the impression of him given by his early biographers as someone uninterested in the theoretical aspects of art. The postilles (marginal notes) in his copy of Vasari’s Lives demonstrate this awareness. Lauding Andrea del Sarto and Michelangelo, Annibale disparaged the “mannered tradition of Florentine painting,”11 noting too the uselessness of comparing Michelangelo with Titian. “Titian’s things are not like Michelangelo’s; they may not be totally successful but they are more lifelike than Michelangelo’s; Titian was more of a ‘painter’…and if Raphael was superior in some parts to Titian, Titian nonetheless surpassed Raphael in many things.”12

Apparently no less contemplative than his scholarly brother or intellectual cousin, Annibale joined them both in their first major commission–two rooms in the Palazzo Fava in Bologna, secured through family connections and their willingness to work at a discounted rate, beginning the project about 1583. The smaller room, which was to contain a frieze about the myth of Europa, was assigned to Annibale and Agostino, while Ludovico, the older and at that time accepted head of their workshop, tackled the larger one, which would tell the story of Jason and the golden fleece. Before all the frescoes were completed, the brothers would join their cousin in the more important space.13

[slide 6: The Meeting of Jason and King Aeëtes (c. 1584, fresco). Palazzo Fava, Bologna, Italy.

The Meeting of Jason and King Aeëtes (c. 1584, pen and black ink with gray-brown wash over black chalk, squared twice in black and red chalk, 10 x 12⅜ in [25.4 x 31.5 cm]). Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich, Germany.]

Annibale’s small ink drawing squared twice for transfer that illustrates The Meeting of Jason and King Aeëtes (c. 1584) shows the composition in a well advanced state as probably presented to the patron, Count Filippo Fava. On the verso containing one of the earliest studies, Annibale had inked figures in their respective perspectival planes, including the accompanying termine,14 those illusionistically painted statues that framed the fresco panels.

[slide 7: The Meeting of Jason and King Aeëtes (c. 1584, pen and black ink with gray-brown wash over black chalk, squared twice in black and red chalk, 10 x 12⅜ in [25.4 x 31.5 cm]). Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich, Germany.

Orpheus Holding a Lyre (before 1584, oiled black chalk over black chalk, heightened with white chalk, on gray-blue laid paper, mounted on wove paper, 16⅓ x 9⅓ in [41.5 x 23.8 cm]). National Gallery of Art, Ontario, Canada.]

Following such compositional imaginings and before the construction of the modello for his client, the artist would research individual poses,15 using not just models from the studio but also from his recollections of previously observed persons and/or sculpture. Annibale’s Orpheus Holding a Lyre (before 1584) shows how well stocked his pictorial memory bank already was. Too general to have been a life study, it might also have been based on one already executed, or refer to some other two-dimensional image.

Lauded for his visual memory, Annibale was reported to have told a friend that “he never–except once, with certain bas-reliefs–had to record for purposes of future recall anything he had looked at carefully.”16 As a group, the Carracci made a regular practice of honing their ability to mentally retain what they had observed. Upon returning home from life drawing sessions and before doing anything else, they would each pick up a scrap of paper and endeavor to commit to it what they had just recently seen, enlivening it with more animation than the original pose.17

[slide 8: Polyphemus (early 1590s, black chalk with traces of white heightening on blue-gray paper, laid down, 1611/16 x13⅞ in [42.4 x 35.2 cm]). Galleria degli Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Florence, Italy.]

Another good example of Annibale’s drawing from his internal image bank, the black-chalk drawing of Polyphemus for a later cycle of frescoes at the Palazzo Fava sets an almost caricatured head on a rippling mass of torqued muscle and bone, about to catapult the small boulder gripped by the one-eyed giant. Pentimenti in the hand suggest final figural considerations in an image already close to the painted one, including reflections on the play of light and shadow to be used in the fresco.

[slide 9: Sheet of Caricatures (c. 1595, ink on paper, 7⅞ x 5⅛ [20.1 x 13.9 cm]). British Museum, London.]

Drawn to facial features, Annibale joined his cohorts in exaggerating them in a form of art that derives its name from theirs: caricature. Playful by nature, known for their love of practical jokes,18 always looking to exploit drawing’s potential to distill essence from reality, the artists had fun deliberately distorting the appearance of certain individuals. In a sheet of these faces, Annibale has sketched in the upper left an ordinary looking profile of a man and in the lower right has riffed on this, opening the eyes wider and hooking the nose more. The receding mouth of the man is exaggerated in several of the profiles on the sheet. Such exercises are to be distinguished from the creation of grotesques–products of the imagination.19

Quite opposite in emotional tone, Annibale’s portrait drawings have a quiet intensity, especially those of children, the models for which he drew from youngsters around the studio–“assistants and friends or relatives who frequented the Carracci shop and academy.”20 As with his other subjects, these young people furnished handy objects to study, though Annibale seems to have had a special affinity for the “serious and meditative”21 interiority that children often manifest in their quiet moments.

[slide 10: Profile Portrait of a Boy (1584-1585), red chalk on ivory paper, 813/16 x 6⅜ in [22.4 x 16.2]). Galleria degli Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Florence, Italy.]

In the early red-chalk drawing Profile Portrait of a Boy (1584-1585), the artist has posed the lad in strict profile and taken considerable care to sculpt his form with light and shadow, gently blending strokes on the smooth-skinned cheek and distinctly denoting the direction of hair strands. Annibale deftly reserved the ivory of the page for the glittering highlights of the hair and the prominent helix of the ear.

[slide 11: Head of a Boy (c. 1585-1590, black chalk on reddish brown paper, laid down, 227/16 x 915/16 in [316 x 252 cm] including a 2 cm horizontal strip added at the top). Musée du Louvre, Départment des Arts Graphiques, Paris, France.]

A similarly finished portrayal, the black-chalk Head of a Boy (c. 1585-1590) captures the tension of the neck muscle as the child strains to look with wide-eyed concern at something on his right. The down-turned corners of the mouth impart a melancholy mood, suggesting that whatever is outside the viewer’s field of vision might not be welcome. As with the earlier portrait, here too Annibale is far less interested in the clothing than in the boy’s head.

[slide 12: Head of a Smiling Young Man (c. 1590-92, black chalk on gray-blue paper with added strips at top and bottom, laid down, 153/16 x 97/16 in [358 x 240 cm]). Musée du Louvre, Départment des Arts Graphiques, Paris, France.

Madonna and Child in Glory with Six Saints (c. 1591-92, San Ludovico Altarpiece). Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna, Italy.]

Identified as a preparatory sketch for a subsequent altarpiece,22 Head of a Smiling Young Man (c. 1590-92) has been so named because of its perceived happy expression. Yet the face of Saint John the Baptist in the San Ludovico altarpiece, for which it is a study, tells a more complex story of the triumphant validation of miracle that the apparition of the Madonna and child provides, a look for which Annibale was searching in this particular drawing, one unlikely to have been taken from life.

[slide 13: The Lutenist Mascheroni (c. 1593-1594, red chalk heightened with white chalk on reddish brown paper, the lower left corner slightly cut, 163/16 x 113/16 in [411 x 284 cm]). Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, Austria.

The Lutenist Mascheroni (c. 1593-1594, pen and brown ink on cream paper, laid down, the lower left corner cut and made up, 77/16 x 415/16 [188 x 126]). Collection Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

Portrait of the Lutenist Mascheroni (c. 1593-1594, oil on canvas, [305/16 x 253/16 in 77 x 64 cm]). Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden, Germany.]

For The Lutenist Mascheroni (c. 1593-1594), another preparatory drawing, Annibale picked up his red chalk again and using much the same approach as he did for the earlier Profile Portrait of a Boy, brought the picture to a high level of finish, perhaps to serve as an immediate model for the painting.23 That the eyes are similarly out of convergence in all three versions implies that Annibale deliberately arranged Mascheroni’s facial features to block eye contact with the viewer. Posed stiffly, the disengaged lutenist reveals little about himself–a common feature of this artist’s portraits24–but a lot about Annibale’s own interpersonal style and his tendency to treat people as objects rather than subjects.

The studies of male nudes for the herms and ignudi that adorn the haunches of the Palazzo Farnese’s barrel vault, however, seem far more animated, exuding sensual energy. When the newly appointed nineteen-year-old Cardinal Odoardo Farnese decided to decorate various rooms in his palazzo in Rome, he would have none other than the Carracci.25 Annibale as the first to become available, arrived in the antique city to begin work in November 1595,26 the beneficiary of what seemed like an unparalleled opportunity but one that ultimately led to disappointment, despair and death.

[slide 14: Project for the Decoration of the Farnese Gallery (1597-98, red chalk with pen and brown ink on cream paper, 15 ¼ x 10⅜ in [38.8 x 26.4 cm]). Musée du Louvre, Départment des Arts Graphiques, Paris, France.]

After first completing the Camerino (the Cardinal’s study), Annibale was joined in 1597 by his brother Agostino to assist him with the much larger project of the ceiling of the Farnese gallery.27 After playing with various concepts in a series of ink drawings, Annibale settled on an illusionistic array of framed paintings covering two-dimensional architectural elements supported by herms, and a frieze of scenes framed by ignudi, eschewing a single point of view for the entire project.

[slide 15: Palazzo Farnese Ceiling (fresco, 1597/98-1601). Rome, Italy.]

When Agostino “pressed for a unified illusion based on one-point perspective,” Annibale mocked his brother’s idea by suggesting they install a sumptuous chair at the only spot in the huge room from which the paintings would be viewable in a way that made spatial sense to the onlooker.28 The result of the lead artist’s decision was a design that could be read from any place in the room, but one that would always include some upside-down images.

[slide 16: Atlas Herm with Arms Raised (1598-99, black chalk heightened with white on gray-blue paper, 189/16 x 14¼ in [47.2 x 36.3 cm]). Biblioteca Reale, Turin, Italy.]

Atlas Herm (1598-99, red chalk on cream paper, laid down, 13⅝ x 713/16 in [34.5 x 19.8 cm]). Musée du Louvre, Départment des Arts Graphiques, Paris, France.]

To create the three-dimensional architectural illusion of his intentions, Annibale had to turn flesh into stone.29 Atlas Herm with Arms Raised (1598-99), the end drawing result of one such attempt, shows how he enhanced an original male nude study by pumping up the muscles and juxtaposing bright highlights with lower-value black chalk to impart a marmoreal quality to the form. Highly unusual for Annibale is the come-hither direct eye contact the herm makes with the beholder–originally the artist. The turned-away head in the lower left might represent some second thoughts but in the fresco Annibale kept to his original idea.

In returning to red-chalk in a different Atlas Herm (1598-99), at a time when he favored black and white chalk on blue paper,30 Annibale might have wanted to take advantage of the medium’s potential for rendering the warmth of flesh. In comparison with the Atlas Herm with Arms Raised, this herm would then represent an earlier stage in the transformation of the living model into a marble sculpture.

[slide 17: A Seated Ignudi with a Garland (1598-99, black chalk heightened with white chalk on gray paper, 16¼ x 16⅛ in [41.2 x 41 cm]). Musée du Louvre, Départment des Arts Graphiques, Paris, France.

Detail of Ignudi and Herms, Palazzo Farnese Ceiling (fresco, 1597/98-1601). Rome, Italy.]

Inspired by Michelangelo’s male ignudi on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican,31 Annibale populated his Farnese vault with analogous figures. Lightly sketched construction lines and first-thought contours in A Seated Ignudi with a Garland (1598-99) provide a window into the artist’s drawing process. Among other changes, he reduced the size of the proper right lower leg, further accentuating the tapering of the massive torso toward the pelvis and legs. In making that choice, Annibale further demonstrated his preference for design over accurate perspective.

[slide 18: Study of a Recumbent Nude, Lying on his Side (n.d, black chalk with white and pink heightening, on gray-blue paper, 14½ x 19⅔ in [36.8 x 49.9 cm]. Royal Library, Windsor, England.

Study of a Recumbent Nude, Viewed from the Head (n.d., black chalk with white heightening on gray-blue paper, 8½ x 15½ [21.5 x 39.5 cm]). Musée du Louvre, Cabinet des Dessins, Paris, France.]

Very different in overall appearance are two black-chalk life studies executed during Annibale’s Roman sojourn,32 each a Study of a Recumbent Nude, one Lying on his Side and the other Viewed from the Head. In the former, the artist has faithfully observed the unadorned truth of the effect of gravity on muscle and skin, particularly noticeable where the bones jut out along the uppermost contour of the rib cage, pelvis and greater trochanter. Unlike in Annibale’s imaginative male nudes, here only the left biceps is rounded, accurate for a flexed position, the right one being flat as appropriate for extension.

Annibale was less satisfied with reality in Study of a Recumbent Nude, Viewed from the Head, thickening the left thigh considerably and, less so, the right arm. This drawing might have started out as a life study and accrued revisions along the way, including a slight change in pose for better effect. Both drawings bear witness to the artist’s intense absorption in the task at hand.

Content in the practice of his art, Annibale never adjusted to the rarified atmosphere and courtly trappings of the Palazzo Farnese, preferring instead the solitude of his room and the company of his students. Minimally attentive to his physical presentation and melancholic in disposition, he actively avoided any unnecessary association with nobility. On an evening stroll when caught carrying a knife, Annibale’s chosen silence about his service to the Cardinal led to time in jail. Likewise, at another time on learning of an impending personal visit from the Pope’s nephew, he escaped through a side door.33

[slide 19: An Execution (1600-03, pen and brown ink on dark cream paper, laid down, 7½ x 119/16 in [19 x 29.3 cm]). Collection Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.]

In Rome, Annibale’s idiosyncrasies stood out far more than they did in Bologna,34 causing no small distress to an already sensitive soul. No wonder, then, that he would be drawn to the ritual of a public hanging, capturing the salient details with brown ink in An Execution (1600-03). In the pictured narrative, as an audience peers over the back wall, exercising its communal responsibility in a purification rite designed to ensure the conversion and repentance of the condemned, a friar holds up a devotional image for the criminal to ponder as he is dragged up the ladder to the gallows,35 his fate foretold by the hanging corpse nearby. Another instrument of death awaits employment on a table to the right.

For Annibale, life soon imitated the morbidity of a hanging when the payment he received for eight years of loyalty to the Farnese projects failed to meet his expectations and in fact, proved to be more of an insult than a reward. The five hundred gold scudi brought on a saucer to the artist’s quarters, perhaps the result of the machinations of a sycophant at court, plunged Annibale into a depression from which he never recovered.36

In the summer of 1605, before tackling the Cardinal’s next project–the decoration of the great hall of the Palazzo Farnese–Annibale fled permanently from the court bustle, seeking seclusion in lodging behind the vineyards of the Farnesina across the Tiber. Later he took up residence on the Quirinal Hill, where the open air and pleasant view could have been more conducive to recovery.37 By 1606 he was in yet another area of Rome some distance from the Palazzo.38

The nature of his illness was such that Annibale experienced intermittent periods of productivity during which he produced a few paintings, supervised and assisted with projects by his students–especially his favorite, Domenichino39 –and continued to draw. He even began to experiment with a new technique, using a thick-nibbed pen (perhaps made of reed) and skipping any ink wash.40

[slide 20: Danaë (1604-05, pen and brown ink on cream aper, laid down, upper right corner cut, 7⅝ x 10⅛ in [19.4 x 25.7 cm]). Collection Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

Titian, Danaë (1545, oil on canvas, 47.2 × 67.7 in [120 × 172 cm]). Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy.]

After a hiatus of four years during which he had resigned from painting, Annibale resumed activity for a few years beginning in 1604,41 accepting a commission from Camillo Pamphilj to paint a Danaë. Perhaps challenged by the presence of Titian’s painting of the same subject in the Palazzo Farnese,42 the artist borrowed the general idea from the Venetian painter of a reclining female nude, on a bed, in a landscape setting, along with the voluptuous form of her body, changing the pose of the princess and the position of Cupid to make the composition his own. Manipulating the thick-nibbed pen to produce both fat and thin lines, Annibale has his Danaë (1604-5) eagerly reaching for the gold coins as they descend from above and come to rest on her left inner thigh.

[slide 21: Self-Portrait on an Easel and Other Studies (c. 1604, pen and ocher-brown ink on cream paper, 9¾ x 7⅛ in [24.8 x 18.1 cm]). Collection Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

Daniele da Volterra (Daniele Ricciarelli), Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) (c. 1544, oil on wood, 34¾ x 25¼ in [88.3 x 64.1 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.]

Self-Portrait on an Easel (c. 1604, oil on canvas). The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.]

The period of relative inactivity was bracketed by two self-portrait drawings, the later one a meditation on portraiture in general and perhaps more specifically, on the artist’s own legacy. In a picture related to the painting Self-Portrait on an Easel (1604), Annibale has positioned a bearded, older man resembling Michelangelo to the right of his arrangement of images that strike poses similar to that of a portrait of this revered forebear (Ricciarelli’s oil on wood) that resided at the Palazzo Farnese from 1600 onward.43 In addition, a similar profile portrait of a seventy-one-year-old Michelangelo introduced a biography of him that had been circulating in Rome since 1553.44

Multiplying his own image, Annibale suggested mirrors, windows, picture frames and the interior of a studio inhabited by a painted canvas on an easel, accompanied by a small menagerie of household pets. Again, inked lines vary in thickness, and darks are indicated by overlapping and hatched lines. The self-portrait in the finished painting is all eyes, wide open, looking out at the viewer, while the mouth disappears into a blur of shadow, an apt representation of an artist not known for eloquence.

[slide 23: Self-Portrait (c. 1600, pen and brown ink on buff paper, laid down on another sheet on which is drawn a decorative border in pen and black ink with gray wash over graphite, 5¼ x 4 [13.3 x 10.2 cm]). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California.]

Although done about 1600, the earlier of the two self-portrait drawings from this period resonates well with Annibale’s last days. Depicting himself leaning on the picture frame, the artist rendered his visage in fading brown ink, cast a shadow over eyes with lowered lids of sadness, turned down the corners of his mouth in a frown, and darkly superimposed over the top of the cartouche a suggestion of a skull.45

Both self-portraits portend death, undoubtedly reflecting Annibale’s deteriorating physical and mental condition. On July 16, 1609, he “died miserably.”46 Since then writers have made much of Annibale’s melancholic disposition47 and its link to his ultimate demise.48 Most likely he died from tertiary syphilis. In his biography of the artist, Bellori asserted that his “death…was hastened by amorous maladies of which he had not told his doctors”49 and in fact, the artist’s symptoms as described by Mancini50 and Agucchi51 conform to those of end-stage syphilis.52

Though the world lost a master draftsman when Annibale Carracci died prematurely at the age of forty-nine, it gained a treasure trove of drawings, cherished enough to survive the centuries. Among those who looked to the Bolognese artist for inspiration was a certain Dutch painter living in Amsterdam in the seventeenth century. The owner of a drawing of people swimming in a landscape penned by Annibale was none other than Rembrandt himself. Unfortunately, the exact identity of the scene has yet to be determined.53

__________________________________

1 Giovanni Pietro Bellori, The Lives of Annibale & Agostino Carracci, trans. Catherine Enggass (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1968), 7.

2 Carlo Cesare Malvasia, Malvasia’s Life of the Carracci, Commentary and Translation, translated and annotated by Anne Summerscale (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press), 250–51, 254.

3 Ibid., 251.

4 Bellori, 16.

5 Donald Posner, Annibale Carracci: A Study in the Reform of Italian Painting Around 1590, Vol I (New York: Phaidon Publishers, 1971), 9.

6 Daniele Benati, et al, The Drawings of Annibale Carracci (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1999), 49.

7 Posner, 23.

8 Ibid., 24.

9 See Landscape with the Setting Sun (1605-09) in Benati, et al, 289.

10 The Metropolitan Museum of Art online object label. Accessed April 9, 2015: http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/ search/338420?rpp=30&pg=1&ao=on&ft=annibale+carracci+drawings&pos=7&imgno=0&tabname=label.

11 John Gash, “Hannibal Carrats: The Fair Fraud Revealed,” Art History 13:2 (June 1990), 245.

12 Ibid.

13 Posner, 53-54.

14 Benati, et al, 58.

15 Benati, et al, 44-45.

16 Malvasia devoted many pages to describing Carracci pranks. See 274-289.

17 Malvasia, 290.

18 Ibid., 267.

19 Posner, 66.

20 Ibid., 20.

21 Ibid., 21.

22 Benati, et al, 96.

23 Ibid., 25.

24 Posner, 21.

25 Gail Feigenbaum in Benati, et al, 109.

26 Posner, 78.

27 Feigenbaum in Benati, et al, 110.

28 Ibid, note 22.

29 Benati, et al, 190.

30 Ibid., 193.

31 Ibid., 194.

32 Carl Goldstein, Visual Fact over Verbal Fiction (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 98-100.

33 Bellori, 58-59.

34 Posner, 146.

35 Mitchell B. Merback, The Thief, the Cross and the Wheel: Pain and the Spectacle of Punishment in Medieval and Renaissance Europe (Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press, 1999), 145.

36 Bellori, 52.

37 Malvasia, 222-223.

38 Kate Ganz in Benati, et al, 204.

39 Posner, 148.

40 Ganz in Benati, et al, 205.

41 Posner, 147.

42 Benati, et al, 278.

43 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, catalog entry for Daniele da Volterra (Daniele Ricciarelli), Michelangelo Buonarroti. Accessed April 21, 2015. http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/436771?rpp=30&pg=1&ft=Jacopo+del+Conte&pos=1&imgno=0&tabname=object-information.

44 Engraving by Giulio Bonasone, Bust Portrait of Michelangelo at Seventy-One, Facing Right (1546), used by Ascanio Condiri in his biography of Michelangelo, published in Rome 1553. On view April 23, 2015 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

45 Benati, et al, 143.

46 Malvasia, 226.

47 Bellori, 55.

48 Ganz in Benati, et al, 204.

49 Bellori, 63.

50 Rudolf and Margot Wittkower, Born Under Saturn: The Character and Conduct of Artists: A Documented History from Antiquity to the French Revolution (New York, Random House, 1963), 114.

51 Malvasia, 227.

51 Wikipedia, Tertiary Syphilis. Accessed April 21, 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Syphilis#Tertiary.

52 Catherine Loisel Legrand in Benati, et al, 25.

Posted in Art Historical Musings |

Print This Post Print This Post

January 3rd, 2015

Identity Dilemma:

Greco-Roman Egyptian

Mummy Portraits at

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

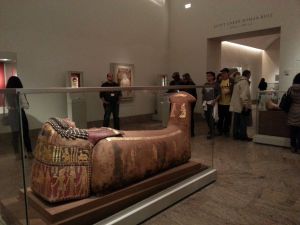

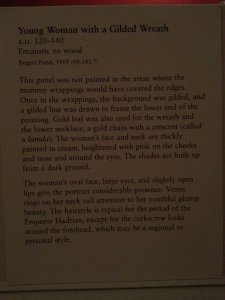

![View of “Young Woman with Gilded Wreath” in Vitrine, Egypt, Roman Period (120–140 CE, encaustic with gold leaf on wood , 14⅜ x 7 in [36.5 x 17.8 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo © Deborah Feller.](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Young-Woman-in-Vitrine-1-225x300.jpg) View of “Young Woman with Gilded Wreath” in Vitrine, Egypt, Roman Period (120–140 CE, encaustic with gold leaf on wood , 14⅜ x 7 in [36.5 x 17.8 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo © Deborah Feller. Crowned by light, the lovely young lady with forehead-framing corkscrew curls and golden hair ornament inhabits a tall, slim vitrine intended to suggest a coffin to the viewer, providing a reminder of her original function as a portrait panel nesting in the linen wrappings of an Egyptian mummy. 1 The encaustic painting, set off dramatically against a warm red display mat, might feel far more at home exhibited with other representatives of early Western European artistic traditions.

When asked how this work, Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath, came to reside in the gallery of Egypt Under Roman Rule 40 B.C. – 400 A.D. at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Marsha Hill (co-curator of the 2000 show Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt) replied that when the work became available for purchase in 1909 from Cairo antiquities collector and dealer Maurice Nahman, the Egyptian Art Department pursued its acquisition using Rogers Fund money; at the time, the Greco-Roman Art Department expressed no interest in any of the Egyptian panel paintings then appearing on the market. Thus, the circumstances of the artwork’s acquisition largely determined its ultimate context2 and how future museum goers would come to perceive this example of Greek-influenced Roman-era painting.

In the early twentieth century, the Met’s Egyptian Art Department demonstrated impressive foresight with its enthusiasm for artwork from the land of the Nile deemed a “classical development” by most Egyptologists and of little importance to classicists who associated the mummy portraits with Egypt (not Greece or Rome).3 Even in the twenty-first century, a recent book about ancient Egyptian art failed to include any reference to these mummy portraits,4 and an exhibition catalog on Egyptian portraiture concluded with a beautiful example of a Roman mummy plaster mask but failed to mention the contemporaneous and identically used panel paintings.5

Across the Great Hall from the Egyptian wing at The Metropolitan Museum, in the relatively new Greco-Roman galleries, there are only four examples of Greek painting displayed–all small murals and predating by several centuries Young Woman and her kind. One is Lucanian from southern Italy; the other three are from the Alexandria region of Egypt. Whether or not an argument was ever advanced for placing the latter in the Egyptian wing, a case could certainly have been made for exhibiting the Greco-Roman Egyptian mummy portraits somewhere among the museum’s extensive holdings of Roman wall paintings.

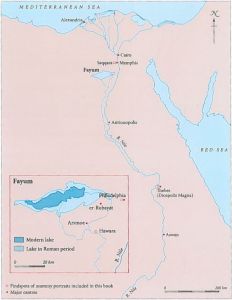

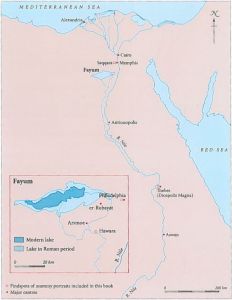

When the Ptolemies took control of Egypt after the death of Alexander in 323 BCE, they drained part of the Fayum lake and built an advanced irrigation system to create additional arable land that they then gave to their Greek soldiers, following an already existing practice. Egyptians were later recruited to work on this newly inhabited farmland and after 30 BCE, both these groups were joined by Romans carrying out the business of empire.6 Art like Young Woman, emerging from this conglomeration, was bound to defy easy categorization.

Conceding that they represent a “confluence of Greek painting, Roman portraiture and Egyptian burial practices,” curator Hill explained that an effort has been made to provide a context for the mummy portraits in the room with Young Woman and in the area where the display continues past the nearby gallery-titled doorway. As an example, she pointed to a vitrine there that encases an intact mummy7 intricately wrapped in linen bands with its portrait panel still in place. Rather than serving to emphasize the Egyptian pedigree of these Roman-period portraits, the mummy highlights the startling contrast between the ancient and contemporary burial and artistic practices of its time.

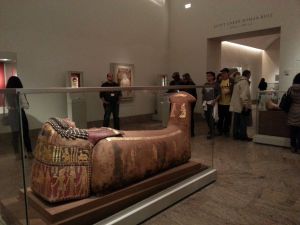

View of “Egypt Under Roman Rule” Gallery at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo © Deborah Feller. The museum succeeded in situating Young Woman in an Egyptian context primarily through its physical location. Entering the gallery that contains the painting, visitors are introduced to the entire Egyptian wing by a sign containing text and photos highlighting the collection, and an ancient tomb structure from Saqqara. Crossing the large room on the way to the far wall of mummy plaster masks, painted shrouds and panel portraits, they encounter two coffins from the Roman period decorated with images of deities associated with Egyptian burial practices.

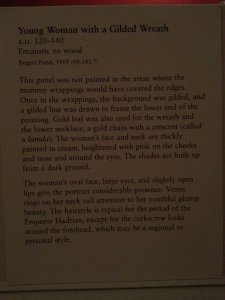

Object Label for “Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath” at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo © Deborah Feller. Casual viewers attracted to Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath who read the picture’s accompanying label learn nothing of how an object so uncharacteristic of Egyptian art came to be displayed in that wing. The text describes the painting as a work of art–with notes on technique, appearance and dating–and gives nothing of its history.8

Visitors never learn that before being displayed as an art object, Young Woman functioned to ensure safe passage to the netherworld and, consequently, eternal life for its subject. Meant to act as backup in case harm came to the physical self (preservation of the body being essential to the continuation of the ka [spirit]),9 long ago severed from its body and home, now exhibited out of context, the mummy portrait as shown tells an incomplete story.

Map of Fayum Lake District from Paul Roberts, Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt (London: the British Museum Press, 2008). For The Metropolitan Museum, that story probably began in the late 1880s with the rediscovery of mummies with painted faces in the Fayum lake district in northern Egypt. Tempera examples were already saturating the market when British archaeologist, Flinders Petrie, excavating at Hawara in that area, came across a trove of encaustic portraits10–soon to prove more appealing to contemporary Western eyes than the previously discovered tempera ones.11

Most of Petrie’s finds ended up in London at the National Gallery and British Museum;12 some found their way to dealers like Nahman. Over the course of time, mummy portraits were unearthed throughout Egypt, though they still continued to carry the epithet “Fayum.”13 Unprovenanced, if Young Woman did originate from that lake district, the discoverer might have provided a service by rescuing it from likely destruction had its burial place been in the path of mid-nineteenth-century farmland expansion, a response to economic incentives and technical assistance from England for Egypt to produce more cotton.14

The civil war tearing apart the United States in the 1860s had halted that country’s exportation of cotton and created new European markets for Egyptian farmers in the fertile Fayum region. “[F]armers…in search of sebbakh,…Nile mud enriched with human- and animal-produced organic materials”–a cheap source of excellent fertilizer, and raw material for mudbricks and saltpeter (used in gunpowder)15–widened their search for this much prized commodity. As farmland reached ancient settlements, and ruins became more valuable as agricultural resources, farmers lost motivation to preserve and sell unearthed antiquities as was their previous custom.16

While sebbakh was more plentiful around town mounds–not necessarily in the area of necropolises,17 related population expansion and its attendant pressures constituted other threats. Had Petrie and his ilk not excavated and removed these paintings–and in the case of the former, given many to public institutions–the portraits might have been destroyed, or hidden away in private collections, Egyptian antiquities law at the time being as lax as it was.18

In the current century, objects of questionable provenance are increasingly repatriated to the countries from which they were removed,19 and national and international antiquities laws make legal exportation of cultural patrimony almost impossible.20 But up until 1912, Egyptian laws on the books since 1835 allowed for easy acquisition of excavation permits with the proviso that finds be split equally with the state.21

Digging up mummies, separating them from their masks, shrouds and/or panel paintings, and then removing them and their accessories for sale by dealers headquartered in Cairo would have been considered sacrilegious by the elite, mostly Greek and Egyptian early-first-century residents of the Fayum region22 who entombed their dead in accordance with ancient beliefs, but at the time it was happening it wasn’t even illegal. With no constituency left to speak for them, the two-thousand-year-old mummies were fair game.

This contrasts with far more recent twentieth-century disinterments, a potent example of which was the 1991 discovery of human remains in downtown New York City during a “cultural resource survey” that included “archeological field-testing” in advance of the construction of a federal building. Identified as a burial ground for African slaves, the site quickly attracted attention from the African-American community and its supporters. After years of productive research agreed upon by all parties, the long-ago-forgotten Africans were reburied at the original site, now a national monument–the African Burial Ground Memorial.23

Similarly, in 1990 the United States passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, providing a process for the return of Native American remains and their related artifacts already in museum and federal agency collections. The law also set down procedures respecting new burial ground discoveries, acknowledging their spiritual importance to surviving tribes.24

The mummies that Petrie, other archaeologists, treasure hunters and farmers were unearthing in the late 1800s, early 1900s, and even before, don’t seem to have been considered by anyone as ancestral remains. Egyptian statutes governing these practices regulated antiquities dealers, not the treatment of the buried dead.25 When The Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased Young Woman in 1909, the action engendered no controversy, their being no Greco-Roman-Egyptian descendants to make a fuss.

In fact, probably with the motivation to present the mummy portrait Young Woman as a work of art rather than a funerary object, someone had flattened what was originally a convex panel and mounted it on a board. Whether the curve was part of the original form or had developed over time with use,26 the retaining of that bowed shape by the excavator/dealer/collector would have made storage and/or shipping inconvenient, rendering the piece less desirable.

![Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath, Egypt, Roman Period (120–140 CE, encaustic with gold leaf on wood , 14⅜ x 7 in [36.5 x 17.8 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo © Deborah Feller.](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Young-Woman-w-Gilded-Wreath-225x300.jpg) Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath, Egypt, Roman Period (120–140 CE, encaustic with gold leaf on wood , 14⅜ x 7 in [36.5 x 17.8 cm]). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo © Deborah Feller. According to curator Hill, other than the alteration in the panel’s shape the surface of Young Woman appears pretty much as it was when found. 27 Although the four vertical fissures that probably resulted from the flattening were filled in, along with some minor cuts, 28 the painting underwent no comprehensive restoration by a conservator intent on imposing upon it some contemporary aesthetic ideal. Fortunately, the portrait retains enough of its original wax pigment and gold leaf to satisfy as both a thing of beauty and a historical document.

If any record chronicled something of Young Woman’s original condition, it would be found in the Maurice Nahman Archives.29 In the absence of such a reference, it seems safe to assume that this portrait panel belonged with others described by Petrie “as [being] fresh as the day they were painted.”30

Displayed to emphasize its aesthetic value, Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath showcases its creator’s skill in the rendering of three-dimensionality, rarely of interest to Pharaonic Egyptian painters. Illumination from the upper left throws warm shadows to the right of prominent forms, while a cool grey tone signals where these forms turn from the light, an effect most obvious along the bridge of the nose and the front plane of the face where it meets the only side visible to the viewer.

Those tricks of the trade surely originated with the great masters of Greek painting chronicled by Pliny the Elder (around 77-79 CE) in Book XXXV of his Natural History31 and took on a new life during the Renaissance, Baroque and later Neoclassical periods of European painting. Nature is not the only teacher here, however. Young Woman’s larger-than-life eyes–like those found on many other mummy portraits–bring to mind ancient Egyptian wall paintings of profile faces with over-sized, kohl-lined eyes.

Viewer in the “Gallery of Egypt Under Roman Rule 30 B.C. to 400 A.D.” at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo © Deborah Feller. Ordinary museum goers, stopping to admire the dramatically-lit, unusual painting in the corner of a room containing a reconstructed Egyptian tomb, probably wouldn’t notice its finer points of technique nor, because of the way Young Woman is currently presented, would they be aware of the critical function the painting once served. For that matter, no person can know the thoughts of the aggrieved who commissioned the portrait for someone so young32 when seeing it for the first time, probably already held in place by the linen enwrapping the mummified body. In these many ways, the identity of Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath has yet to be fully understood and adequately presented.

____________________________

1 Marsha Hill, Curator of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, interview by author, New York, October 28, 2014.

2 Ibid.

3 Morris Bierbrier, “The Discovery of the Mummy Portraits” in Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt, edited by Susan Walker (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000), 33.

4 Gay Robins, The Art of Ancient Egypt, revised edition (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2008).

5 Donald Spanel, Through Ancient Eyes: Egyptian Portraiture (Birmingham, Alabama: Birmingham Museum of Art, 1988).

6 R. S. Bagnall, “The Fayum and its People” in Ancient Faces, 26-28.

7 Hill, interview.

8 The Metropolitan Museum, object label, Young Woman with a Gilded Wreath, read on October 28, 2014.

9 John Taylor, “Before the Portraits: Burial Practices in Pharaonic Egypt” in Ancient Faces, 9.

10 Nicholas Reeves, Ancient Egypt: The Great Discoveries, A Year-by-Year Chronicle (London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2000), 76-78.

11 Ibid.

12 Bierbrier in Ancient Faces, 32.

13 Ibid., 33.

14 Paola Davoli, “Papyri, Archaeology, and Modern History,” The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri Lecture Series, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, n.d., accessed October 24, 2014, http://tebtunis.berkeley.edu/lecture/arch.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Hill, interview.

18 Davoli, “Papyri, Archaeology, and Modern History.”

19 For example see: Jason Felch, “Getty ships Aphrodite statue to Sicily,” Los Angeles Times, March 23, 2011, accessed November 4, 2014, http://articles.latimes.com/2011/mar/23/entertainment/la-et-return-of-aphrodite-20110323; and Elisabetta Povoledo, “Ancient Vase Comes Home to a Hero’s Welcome,” New York Times, January 19, 2008, accessed November 4, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/19/ arts/design/19bowl.html.

20 “International Antiquities Law Since 1900,” Archaeology, April 22, 2002, accessed November 4, 2014, http://archive.archaeology.org/online/features/schultz/intllaw.html.

21 Davoli, “Papyri, Archaeology, and Modern History.”

22 R. S. Bagnall in Ancient Faces, 28-29.

23 “African Burial Ground Memorial, New York, NY,” Historic Buildings, US General Services Administration, accessed November 8, 2014, http://www.gsa.gov/portal/ext/html/site/hb/category/25431/actionParameter/exploreByBuilding/buildingId/1084#.

24 “National NAGPRA, Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act,” National Park Service, U. S. Department of the Interior, accessed November 8, 2014, http://www.nps.gov/nagpra/mandates/25usc3001etseq.htm.

25 Davoli, “Papyri, Archaeology, and Modern History.”

26 Hill, interview.

27 Ibid.

28 Catalog entry, Ancient Faces, 109.

29 “Maurice Nahman, Antiquaire. Visitor book and miscellaneous papers. 1909-2006 (inclusive),” Wilbour Library of Egyptology. Special Collections Brooklyn Museum Libraries, Brooklyn Museum, accessed November 8, 2014, http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/archives/set/73/maurice_nahman_antiquaire._visitor_book_and_miscellaneous_papers._1909-2006_inclusive.

30 Reeves, Ancient Egypt: The Great Discoveries, 78.

31 Pliny the Elder, Natural History, translated by D. E. Eichholz (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press and London: William Heinemann, 1949-54), Vol. 10, Book XXXV, 38-53.

32 The existence of portraits of young children as well as the very old make it unlikely the paintings were done during the lifetime of the subject, and CAT scans of mummies show age and sex consonant with still-attached portraits. See Susan Walker, “Mummy Portraits and Roman Portraiture” in Ancient Faces, 24.

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post Print This Post

January 1st, 2015

City House, Country House:

A Tale of Two Madrasas

After 9/11, many Americans came to associate the religion of Islam with terrorism, and madrasas with the recruitment and training of future terrorists. The early history of these “collegiate mosques”1 or “theological colleges”2 (as they have been called) demonstrates their importance as purveyors of propaganda, a common function of all educational institutions. As developed and deployed by the Seljuks of Anatolia, they served as front-line institutions in the battle to restore Sunni orthodoxy, which had all but disappeared by the time Nizam al-Mulk became vizier and de facto ruler of the Seljuk empire3 in the mid-eleventh century, and embarked on his madrasa-building campaign.

Begun with more modest objectives, the earliest madrasas probably operated out of a teacher’s house. Eventually these places of learning grew in size to provide rudimentary lodging for students (all male, of course) as well as space for daily prayers.4 Under the generous patronage of Nizam al-Mulk and his regime, madrasas sprang up in many of the major urban areas in the Near East to counter the significant advances that had been made by the rival Shi’i who practiced a different brand of Islam.5

In addition to consolidating power through the imposition of Sunni state-sponsored institutions of religion, the newly built madrasas provided training for bureaucrats who would then go on to faithfully serve their government. In this way, Nizam al-Mulk transformed what began as a building for study and prayer into one that was used to train “individuals to maintain order and enforce control and power.”6

By 1146 another ruler, Nur al-Din, was in control, having established his base of operations in Aleppo in northern Syria after political and military maneuvers that arrested and repelled the advance of the Crusaders, contained the Seljuks in the north, and consolidated his authority over an ethnically diverse Near-Eastern population. Himself a Turk from Anatolia with a largely Kurdish following, Nur al-Din turned to the already-established notion of jihad (the political and spiritual struggle against non-believers–in this case the Crusaders) to rally this variegated Islamic populace around shared goals.7

Perhaps inspired by the work of his predecessors the Seljuks, Nur al-Din positioned himself as the commander of the jihadist cause and began a building campaign to restore and erect orthodox Sunni structures throughout his territory, deploying religious education as a glue to hold his lands together.8 In Aleppo, a predominantly Shi’i city, he waited three years before building his first madrasa, al-Halawiyya in 1149, initially avoiding a heavy-handed approach that would jeopardize his popularity and control.9 When he was ready to challenge the Shi’is hegemony, he did it openly, situating this new Sunni madrasa opposite the Great Mosque in the madina, the center of the city.10

At the same time, by choosing to erect his madrasa on the skeleton of the Byzantine cathedral St. Helena–already retrofitted for use as a mosque in 1124–Nur al-Din could further triumph over Christianity.11 While nothing is known about the original plan of the church or the changes made to convert it into an Islamic house of worship, at the time of its conversion into a madrasa (or later) changes must have been made to its physical structure.12

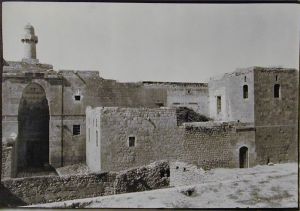

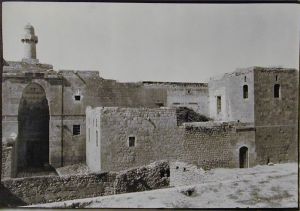

The current appearance or even the continued existence of the al-Halawiyya madrasa remains a mystery. A Syrian civil war attracting foreign combatants has already claimed the lives of many important monuments in Aleppo and elsewhere.13 Tourist reports accompanied by photographs from as recently as 2012 documented a building in use as a mosque, no longer functioning as a madrasa, and in need of serious conservation and restoration work.14

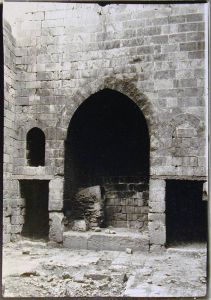

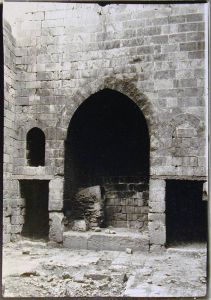

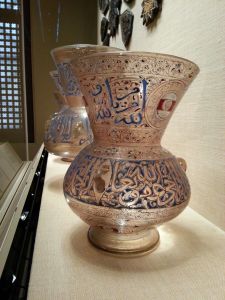

View of Interior Courtyard, Madrasa al-Halawiyya, Aleppo, Syria. Photo taken no later than 2012. Reports, ground plans and photographs from the 1970s and earlier15 describe a building entered through a portal leading to a long corridor that opened into a courtyard with a pool at its center. Across this modest-size open space, a floor-to-ceiling window topped by an arch faced with alternating black-and-white stones demonstrated the inventiveness and skill of Northern Syrian masons.16

View of Church Apse, Madrasa al-Halawiyya, Aleppo, Syria. Photo taken no later than 2012.  Acanthus-leaf Column Capitals, Madrasa al-Halawiyya, Aleppo, Syria. Photo taken no later than 2012. Through the door to the left of the large window lay the remains of the Byzantine church–the main section of the madrasa–beneath a pendentive dome (one of the first of its type in Aleppo), the fine construction of which suggested the architects might have modeled it on what was left of the one for the cathedral.17 Two iwans (rectangular spaces walled on three sides and open on the fourth) branched off the space under the dome to its left and right. Opposite the entrance in a semi-circular apse stood six vintage columns crowned with acanthus-leaf capitals–vestiges of the previous structure.

Carved Wooden Mihrab, Madrasa al-Halawiyya, Aleppo, Syria. Photo taken no later than 2012. On the southern wall of the madrasa interior, an intricately carved wooden mihrab–the locus of all prayers–became the object of intense activity in October 2013 when the Syrian Association for the Preservation of Archaeology and Heritage walled it off behind a protective barrier. Dating to the time of Nur al-Din and renovated one hundred years later by an Ayyubid king, it includes verses of the Qu’ran.18

Much later (in 1660), the Ottoman rulers left their mark on madrasa al-Halawiyya with their renovation of the courtyard façades, commemorating that activity with an inscription over the door to the prayer hall.19 Nur al-Din’s own carved calligraphy, lining three sides of the vaulted corridor leading to the courtyard, was left in place.