News & Views

Print This Post Print This Post

April 3rd, 2011

Biographer Secrest

Questions Authorities

On Artist Amedeo Modigliani

Perhaps a detective in a previous life, Meryle Secrest can’t resist challenging a too-good-to-be-true story. Expanding on her work as a journalist, she relentlessly pursues facts behind myths surrounding larger-than-life artists and their supporters. Secrest’s efforts have thus far produced ten biographies, including psychologically insightful ones on Salvador Dalí and Romaine Brooks. As with her latest, Modigliani: A Life, she ferrets out family and childhood factors to illustrate their influence on the life and artistic development of her subjects. Perhaps a detective in a previous life, Meryle Secrest can’t resist challenging a too-good-to-be-true story. Expanding on her work as a journalist, she relentlessly pursues facts behind myths surrounding larger-than-life artists and their supporters. Secrest’s efforts have thus far produced ten biographies, including psychologically insightful ones on Salvador Dalí and Romaine Brooks. As with her latest, Modigliani: A Life, she ferrets out family and childhood factors to illustrate their influence on the life and artistic development of her subjects.

Undoubtedly a stop on a book tour, Secrest’s talk at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Concerts & Lectures Series on March 19, 2011, gave her fans the pleasure of listening to her narrate the circumstances surrounding the evolution of her latest biography. Curious about the widely accepted version of the life of artist Amedeo Modigliani, she marshaled her ample journalistic skills to go after the truth.

The story of a “darling, gifted artist, willing to live in squalor, who drank and drugged himself to death,” and whose 21-year-old girlfriend, eight months pregnant with their second child, leapt out a window of her parents’ apartment 36 hours after her 35-year-old lover died, reads like a discrete form of “chick lit,” Secrest explained. In keeping with that particular appeal, she added, her publisher selected the photo that it did to use on the biography’s cover.

Part of a group of artists and their friends who gathered in the cafés of avant garde Paris, Modigliani died from tubercular meningitis. Enough bad will and grudges survived him to create the negative images that proliferated after his death.

Secrest loves to tell stories and, during the lecture, offered many about her quest for descendants of people close to Modigliani willing to share material passed down to them. Undaunted by dead ends like tracking down a supposed archive to a museum that never housed them and encountering resistance from the heirs of Jeanne Hébuterne (the ill-fated lover) who refused to speak with her, Secrest hit pay dirt when she located the grandchildren of Paul Alexandre, Modigliani’s first patron. The extensive archive the collector’s family made available to her contained valuable material on her artist.

In addition, Secrest benefited from the assistance of several scholars who, well versed in the man and his times, helped her paint a more nuanced picture of Modigliani, especially concerning his substance abuse. From the Alexandre family, Secrest gathered that the artist never abused alcohol though he drank wine regularly as did his cohorts; he used drugs, legal at that time, seeking to expand his vision.

At this point in the lecture, Secrest introduced the artist’s childhood history, an aspect of her writing that sets her apart from others’ discourses on artists’ lives and works. In the case of Modigliani, the financial losses of his family prior to his birth and the tuberculosis he contracted at sixteen, which would plague him throughout his life, set him apart from his peers. The stigma surrounding his disease forced him to manage his recurrences in secret lest he be whisked away to a life in quarantine, the prevailing treatment at that time. Secrest contends that Modigliani used alcohol and drugs to manage his symptoms and their accompanying pain.

In a 2003 interview with then NEH Chairman Bruce Cole, to his observation that, “You notice other things other people miss,” Secrest replied, “And I love doing that. I think if I had had an education, perhaps I would have become a psychiatrist.” That inclination reveals itself in the way she deduces the powerful impact tuberculosis had on Modigliani’s life.

Secrest spoke of the “violent hemorrhaging and fever” suffered by the teenager, whose survival she attributed to his mother’s persistent caregiving. She then fast forwarded to the adult Modigliani’s fascination with alchemy, death and transformation, relating how he carried around a poem, “a rambling outpouring of rage and despair” by an author who died from tuberculosis at 24. Her conclusion? Modigliani’s surviving such a frightening ordeal explains so much about him.

During the remainder of her presentation, Secrest displayed several slides of Modigliani’s paintings, briefly exploring the connections between his life and his art, then focused on her discoveries about his girlfriend. Analyzing watercolors Hébuterne produced in the months before her death, the biographer surmised that she had planned her suicide well before her lover died.

The lecture ends with the last photo taken of Modigliani and another story, this one about Secrest’s pilgrimage to the artist’s final residence. She kept looking for a happy ending, she confessed, and finally found it in the apartment. Never one to ruin a good tale, Secrest refused to give away the ending, instead directing the audience to her new book.

Posted in Art Historical Musings |

Print This Post Print This Post

April 1st, 2011

Men and Gods

Behaving Badly

- Athena (J. Eric Cook) Preventing Achilles (Dana Watkins) from Attacking Agamemnon

Two men appear out of the darkness on a bare stage laterally framed by long black, purple and gold curtains; in the background a flat screen of pale blue reaches down to the floor. One of the actors begins the recital with a scene-setting description. Miss a few words and lose the context.

Despite paying rapt attention, viewers unfamiliar with the Iliad will still need assistance with the plot from the program insert, Literary Background. Consulting that crib sheet, readers discover that Kings (The Siege of Troy) represents over forty years of effort by English poet Christopher Logue to update the Homeric classic for contemporary audiences.

Logue’s adventures with a poem that originally held little interest for him began back in 1959 as an invitation from the late classicist Donald Carne-Ross to revise certain passages from the ancient Greek epic for a new version to be aired on the BBC. The rewrite evolved into a decades-long immersion in an assortment of other authors’ translations, including a literal one provided by Carne-Ross, and the creation of this and other poems based on sections of the Iliad.

Kings, taken from Books I and II, opens with a supplication by Achilles, the merciless Greek warrior, to his mother, the sea goddess Thetis, that she use her connections to induce Zeus, the king of the gods, to punish the Greek king Agamemnon for taking for his own the woman that Achilles had been awarded following his destruction of her city:

…Briseis, my ribbon she,

Whose fearless husband, plus some 50

Handsome-bodied warriors I killed and burned

And so was named her owner by you all

In recognition of my strength, my courage, my superiority.

In retaliation for that insult, Achilles withdrew his troops from the nine-year-old Greek effort to breach the walls of Troy and gain victory over that city. Seeking further vengeance, he asks the gods to ensure the destruction of the Greeks and their king:

Beg him this:

Let the Greeks burn, let them taste pain,

Asphyxiate their hope, so as their blood soaks down into the sand,

Or as they sink like rings into the sea…

As for Agamemnon, his arrogance and inflated ego (even for royalty) contribute to his inability to recognize the trap the gods set for him when they entice him to order an ill-conceived assault on Troy. Those character flaws also cost him his best fighter.

In the Introduction, Logue explained his decision to retain the original storyline and, inspired by liberties taken by the other writers and mindful of the characters’ intentions, winnow away Homer’s excessive dependence on adjectives, and alter the descriptions and dialog “to make their voices come alive and to keep the action on the move.”

For the most part he has done just that. Some of the strongest scenes contain venomous exchanges between Achilles and Agamemnon, illustrating to the extreme their will to power. At other times, the action slows as the two actors create settings with words or enact other, somewhat peripheral roles that afford little opportunity for character development. Logue delights with occasional insertions of film directions that enhance the contemporary relevance of the poem:

Silence.

Reverse the shot.

Go close.

In the lands of the Iliad, women remain out of sight except as deities and spoils of war. One wonders whether, in the absence of tempering by the feminine traits of empathy and nurturing, such an imbalance leaves men more prone to violence. A murderous lunge by Achilles in answer to Agamemnon’s refusal to change his mind about taking Briseis gets aborted by Athena, acting on Hera’s orders.

`Hera has sent me. As God’s wife, she said:

`Stop him. I like them both.’

I share her view. In any case

We have arranged another death for Agamemnon.

If you can stick to speech, harass him now.

But try to kill him, and I kill you.’

Use words not violence, the goddess dictates. Having little choice, Achilles responds with a volley of vitriol and then storms off. Not quite diplomacy, it does avoid bloodshed, if only for the moment.

Kings (The Siege of Troy)

Handcart Ensemble

Verse Theater Manhattan

Workshop Theater Company

312 West 36th Street, 4th floor

New York, NY 10018

(212) 695-4173

Posted in Theater Reviews |

Print This Post Print This Post

March 11th, 2011

Brain Organ that Monitors Danger

Also Seeks Pleasure

An almond-shaped brain organ, the amygdala has long been associated with translating the sensory input of dangerous situations into the emotion of fear, then signaling the body to prepare for an immediate response, either fight, flight or freeze. Now new research, as reported in Science News, reveals its role in the perception of, and response to, far more enjoyable events.

Well connected to regions of the cerebral cortex that process incoming signals from the five senses, the amygdala works in tandem with the prefrontal cortex, the brain’s command center, to determine optimum actions in the face of threats. Modern imaging tools that can zoom in on neuronal activity have allowed researchers to ferret out amygdala cells that identify, assess, and assign value to, potentially beneficial situations.

Feelings provide valuable information about the environment. It makes sense then that the amygdala, as part of the limbic system—a region of the brain that handles emotional experiences and responses to them—would play a crucial role not just in avoiding danger but also in pursuing goals associated with the pleasurable gratification of needs.

One research team, taking advantage of the availability of a small group of patients who had undergone procedures requiring placement of electrodes in their brains, monitored amygdala nerve cells in subjects evaluating the worth of assorted junk foods. Of the 51 amygdala neurons tracked, 16 demonstrated direct correlation with the volunteers’ ratings of individual treats. Results of a study like this also raise questions about the role the amygdala might play in addiction.

In an experiment that looked at the amygdala’s part in decision making, scientists found one set of nerve cells registered good surprises while another registered bad. Having two distinct types of amygdala neurons evaluating surprise according to positive versus negative content insures the most effective responses to unpredictable events.

To determine which of two brain organs directs the show, other scientists explored connections between the prefrontal cortex, also active in assigning value, and the amygdala. Using unfortunate but very smart monkeys, experimenters short-circuited the amygdala in some of them after training all of them to play a computer game where choosing one picture over another garnered a better reward.

The researchers discovered that even without a working amygdala, monkeys still selected pictures leading to the best outcome on most of the trials. Zeroing in on neurons in the orbitofrontal cortex (sensory integration, sense of self, self-reflection) and anterior cingulate cortex (attention, mood regulation, internal states monitoring , decision making), they detected a decrease in neuronal activity in the latter.

More intriguing, monkeys without a functioning amygdala exhibited no emotional response (determined by pupil diameter and heart rate in response to the reward). Retaining the cognitive ability to select wisely, they lacked any emotional engagement with their successful choices.

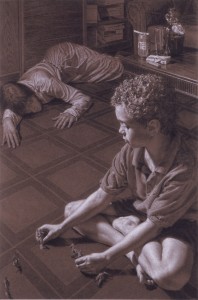

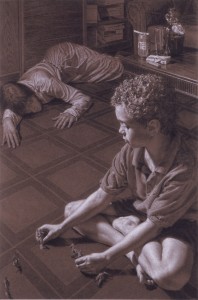

These findings have implications for childhood trauma survivors whose brains developed to cope with brutal, often random, assaults by people expected, and depended upon, for love and care. Stress and trauma have been found to inhibit neurogenesis (cell growth) in the hippocampus, a part of the brain that, working in concert with the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, consolidates all aspects of experience into narrative memory.

Could changes have occurred in nerve cell growth in the amygdala as well? For example, an incest survivor with childhood-based Post-traumatic Stress Disorder who has a hair-trigger response to any form of unexpected touch might have an impaired amygdala rendering her/him unable to distinguish, on the fly, between good touch and bad. A malfunctioning amygdala might also predispose someone to remain in a dysfunctional or abusive relationship, spurning positive ones, if the ability to discern rewards has been affected by early abuse or neglect.

The curious lack of emotional engagement that monkeys minus amygdalas displayed as they selected available rewards seems like anhedonia, the inability to feel pleasure, a symptom of depression. PTSD sufferers often complain about not being able to feel good or even okay. The monkeys’ disconnection between what their cortices know and what their bodies feel also suggests depersonalization, a type of dissociation associated with trauma, where the victim looks at her/himself from a distance. Later in life, survivors complain that their bodies feel alien to them and that they don’t feel anything.

As neuroimaging expands knowledge about the workings of the brain on the cellular level, the potential exists for greater understanding of the way early abuse and neglect affects the developing brain’s ability to react effectively to life’s ups and downs, especially in relationships with others. More effective treatment could then be devised to ensure recovery for all who live with childhood-based PTSD.

Posted in Therapist Musings |

Print This Post Print This Post

March 10th, 2011

Work on Red Leather

Begins

An updated image of the painting Childhood’s Edge can be seen on the Work in Progress page. Work on the turquoise drapery in the background is complete and efforts now turn to the red leather drapery on the shelf.

Posted in Currently on View |

Print This Post Print This Post

March 6th, 2011

American Artist Magazine

Expands Focus to Include

NYC Metropolitan Area

During its several decades of existence and until last spring, American Artist Magazine has brought readers instructional profiles of mostly commercial-grade artists with only occasional forays into coverage of realist artists shown in museums and upscale galleries.

When Michael Gormley became editorial director in March 2010, the magazine began to train a spotlight on the New York City art world. Known to this writer from his days as dean of the New York Academy of Art, Gormley has assigned writers to cover art-historical exhibitions like the Whitney’s show on Edward Hopper and New York-based painters such as Bo Bartlett and Steven Assael. Now the new editor has remembered the East Coast with a spinoff of the annual American Artist’s Weekend with the Masters, always held in California.

With only a few general events so far, the four-day-long “weekend” primarily offers master classes at an assortment of venues with well-respected artist-teachers, including Assael, Alyssa Monks, Jacob Collins, and Odd Nerdrum. Though pricey, the 3½-day workshops promise intensely focused instruction from masters of the crafts of painting, drawing and sculpture.

Those interested can register now to guarantee a space in these limited-size classes. For other sessions, tickets will go on sale later.

American Artist

Weekend with the Masters Intensive

Posted in Art Historical Musings |

Print This Post Print This Post

February 27th, 2011

Emerging from Obscurity:

Artist Marie-Louise von Motesiczky

- The Old Song (1959, oil on canvas, 40″ x 60-1/8″), courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY, © The Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Trust.

The name required pronunciation assistance (think “ch” for “cz”) and bore no hint of familiarity, but the image on the card announcing the first United States exhibition of the work of Austrian artist Marie-Louise von Motesiczky encouraged further investigation. Accompanying the invitation, a brief biography of the artist written by Jane Kallir, the psychologically insightful co-director of The Galerie St. Etienne (the show’s host), provided more than enough reason to visit.

Greeting the viewer entering the room devoted to the story of Motesiczky’s relationship with her mother, The Old Song (1959) depicts the 77-year-old woman in the bed where she’d spent many daytime hours over the course of her life. With one of her loyal greyhounds watching from under the bed, Henriette von Motesiczky listens to her neighbor strum a harp while an eagle floats nearby. The harpist, with ashen face and bright red nails, portends approaching death, though Henriette went on to live another 19 years and to inspire other paintings and drawings by her daughter, many of which joined this work in the gallery.

- Self-Portrait with Straw Hat (1937, oil on canvas, 21-7/8″ x 15-1/4″), courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY, © The Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Trust.

Paradise Lost & Found, the exhibit’s title, refers not to any one particular painting, but more broadly to the life of Motesiczky. Born in 1906 in Vienna into an aristocratic Jewish family inextricably linked to other wealthy Jews through bloodlines and social standing, the artist fled with her mother first to Amsterdam and ultimately to England when the Nazi onslaught began decimating the world they had known. More immediately, young Marie-Louise’s life changed dramatically with the sudden death of her father in 1909.1

Henriette, devastated but emancipated after the death of her husband, and with ample means to live large with few restraints, glommed onto Marie-Louise and never released her. The other child, six-year-old Karl, remained invisible to his mother but benefited from the close friendship and comforting of his loving sister. He would die in Auschwitz in 1944, several months after his arrest by the Gestapo for helping Jews escape from Poland.

To insure her daughter’s continued availability, Henriette intervened whenever romance threatened to shift attachment elsewhere. When 16-year-old Marie-Louise fell in love with her cousin, her mother shipped her off to Holland for a few months and when six years later she wanted to marry a man with whom she shared a serious relationship, her mother forbade it.

Despite her mother’s narcissistic dependence on her, Marie-Louise enjoyed remarkable freedom, perhaps better described as not-so-benign neglect. In early adolescence, she could choose to drop out of school and begin pursuing her interest in art, taking drawing lessons privately.

After World War I ended, new laws designed to ease housing shortages mandated owners of large residences to take in borders. The Motesiczky family, mostly insulated from the upheaval of World War I, became host to a steady stream of paying guests, many with intellectual and/or artistic credentials, who provided illustrious company for the very young Marie-Louise. One, an American architecture student, became a first lover. The tender age of the girl and the laissez-faire attitude of her mother raises troubling questions about the nature of that liaison.

- Fräulein Engelhardt (1926-27, oil on canvas, 24-5/8″ x 23-3/8″), courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY, © The Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Trust.

During the summer of 1920, the German artist Max Beckmann, introduced by a family member, paid a visit to the Motesiczky’s. By playfully entertaining the teenager with an impromptu dinner skit involving a piece of straw dipped in wine, he enthralled the 14-year-old Marie-Louise with his personality, and later his art, laying the foundation for their deep and lasting friendship.

Motesiczky’s educational travels during her teens and early twenties brought her into contact with Dutch art in The Hague and the avant-garde in Paris. Spending time in Frankfurt am Main, she studied directly with Beckmann, already a strong influence on her early art.

As the young artist gained skill and experience, she developed her own unique and emotionally powerful style, evident in the 1926-27 portrait of Henriette’s close friend, the elderly Fraulein Engelhardt. The work blends the angular, flat planes of color and thick application of paint favored by her teacher Beckmann with Motesiczky’s own balanced composition, subtle color, and empathic rendering of the woman’s likeness. Sitting on a cushion-backed chair, the subject of the painting gazes at and points toward a brown, autumnal leaf that rests on the table upon which she leans, as if indicating to the visitor her awareness of approaching death.

- Siesta (1933, pastel & charcoal on tan laid paper, 10″ x 16-3/4″), courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY, © The Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Trust.

- Hunting (1936, pastel & charcoal on paper, 18-1/8″ x 22-3/8″), courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY, © The Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Trust.

The painter did not intentionally set out to focus her art on charting the ravages of time but did so in the many portraits of her mother, whose omnipresence in her life and inclination to recline in bed made her a perfect subject.

At The Galerie St. Etienne, the viewer first meets Henriette at the start of the exhibit in a pair of pastel drawings, Siesta (1933, pastel and charcoal) and Hunting (1936, pastel). In the first, the ample woman, wide-eyed and red-nosed, appears abed, partially covered, hugging her pillow. In the other, Henriette engages in another favorite pastime, hunting. Attired in blue dress, legs splayed to balance herself in a rowboat, she looks down the sight of a brown-handled rifle, intent on her prey.

- Reclining Woman with Pipe (1954, oil on canvas, 28-1/8″ x 40″), courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY, © The Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Trust.

In the room with The Old Song, joining other portraits of the artist’s mother, Reclining Woman with Pipe (1954, oil) captures Henriette at 72. Marie-Louise depicts her mother sporting a grey wig, propped up in bed, enjoying a pipe. Though now much older, the woman appears robust and alert, enlivened by the bright yellow pillow upon which she rests and the red nightgown that slips from her left shoulder, exposing pink skin.

- Mother in the Garden (1975, oil, pastel & charcoal on canvas, 32″ x 20″), courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY, © The Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Trust.

Advanced age suffuses Marie-Louise’s Mother in the Garden (1975, oil, pastel and charcoal). The shadow on the garden wall, cast by sunlight falling on the spectral figure, attests to the old woman’s substance. Stooped over and almost bald at 93, Henriette continues to tend her beloved garden. She would live another three years.

- The Greenhouse (1979, oil & charcoal on canvas, 21-7/8″ x 32-1/8″), courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY, © The Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Trust.

In homage to her mother, Motesiczky created The Greenhouse (1979, oil and charcoal) a year after Henriette’s death. At 73, as an accomplished artist with major portrait commissions and work displayed internationally including a 1966 multi-venue solo exhibition, she confronted not just her mother’s mortality but also her own.

The figure of the artist’s mother, now practically transparent, bends over to rake some fallen leaves in her garden. Close by, two of her greyhounds look toward the barely visible third, a mere outline in front of the brown wood of the pictured structure. A rising/setting sun in a high-value sky illuminates the glass of the greenhouse, less an actual reflection than an imagined one, with a blue stream flowing through bulrushes, a reference perhaps to Henriette’s love of hunting.

- Canetti, London (1965, oil on canvas, 12″ x 10″), traveling exhibition, no. 63, Schlenker 200, © The Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Trust.

Although her mother succeeded in preventing Marie-Louise from ever marrying, she could not stop her from succumbing to the allure of fellow émigré Elias Canetti, a married writer she met in 1939 soon after their relocations to London. Marie-Louise sustained this romantic obsession, with all its pleasure and pain, until her death.

Involved in an affair that afforded her the luxury of maintaining her own autonomy, after the war Motesiczky provided Canetti with a place to write in her new London flat, a great way to insure his company. The arrangement lasted until 1957. Expecting that her status as the other woman would finally change in 1963 when her paramour became a widower, Marie-Louise suffered a devastating shock when ten years later she learned from a friend that he had remarried and fathered a child.

- Self-Portrait with Canetti (1960s, oil on canvas, 20″ x 32-1/4″), courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY, © The Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Trust.

Her Self Portrait with Canetti (1960s) illuminates well Motesiczky’s plight. Dolefully staring at the object of her affection, the artist portrays herself to the left of the items separating them: six paint brushes, two quills and a large flowering plant. Canetti’s attention remains fixed on the newspaper he holds open on his desk; his bushy-haired head, on the right side of the composition, balances not with Motesiczky’s on the left, but with the vegetal display that sits on the table (perhaps representing the wife that Motesiczky blamed for Canetti’s unavailability). Further highlighting their divide, two shining ovals hover in the open space between them.

As she aged, Motesiczky became more open to sharing her art with the world. In 1985, the Goethe Institut in London mounted her first retrospective; others followed elsewhere. The artist, who had always traveled widely, visited Egypt at the age of 84, spent her 87th birthday doing volunteer work in a prison, and continued painting and attending art exhibits during her later years.

In 1996, Marie-Louise von Motesiczky died in London, a few months before her 90th birthday. Four years prior, she had established The Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Charitable Trust in keeping with her initial impulse to create art:

My longing is to paint beautiful pictures, to become happy in doing so, and to make other people happy through them.2

__________________________________________

1 All biographical information from Marie-Louise von Motesiczky, 1906-1996, The Painter, Jeremy Adler and Birgit Sander, editors, 2006.

2 Ibid, dedication page.

Marie-Louise Motesiczky

Paradise Lost & Found

The Galerie St. Etienne

24 West 57th Street

New York, NY 10019

(212)245-6734

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post Print This Post

February 15th, 2011

Turquoise Drapery

Nears Completion

An updated image of the painting Childhood’s Edge can be seen on the Work in Progress page. Work on the turquoise drapery in the background nears completion.

Posted in Currently on View |

Print This Post Print This Post

February 8th, 2011

Skeptical Freud

Challenges

Pious C. S. Lewis

- Mark H. Dold as C. S. Lewis (left) & Martin Rayner as Sigmund Freud (right).

In a room easily mistaken for his office in Vienna, Sigmund Freud sits at his desk bathed in light from the picture window behind him. After listening to a bulletin about Germany’s invasion of Poland, the doctor turns off the radio when musical programing resumes. A dog offstage barks the arrival of his invited guest, the young writer Clive Staples (C. S.) Lewis.

Inspired by a question that appeared in Armand M. Nicholi, Jr.’s The Question of God, about whether the Oxford professor who would later gain renown for his Chronicles of Narnia ever met the father of psychoanalysis, playwright Mark St. Germain turned the imagined conversation of such an encounter into a full-length play, Freud’s Last Session.

As portrayed by Martin Rayner, Freud impresses with his acerbic wit and his stoic attitude toward the cancer that devours his mouth. Ever conscious of the finite nature of life, especially his own, when Lewis apologizes for arriving late, the doctor counters with a quick retort, “If I wasn’t eighty-three I would say it doesn’t matter.”

Mark H. Dold plays the 41-year-old Lewis as the quite proper Oxford intellectual and recent convert to Christianity. Summoned by the elder man, he assumes Freud took umbrage at an unpleasant satirization of him in one of his books. In fact, Freud hadn’t even read the novel and enjoys undermining Lewis’s self-importance by surprising him with that fact.

The doctor had, however, heard about its contents from a colleague and felt the need to personally interrogate a former atheist newly enthralled by God. Comprising the only action in the play, their dialog ranges widely, punctuated by the BBC’s coverage of the 1939 events leading up to World War II, Freud’s oral cancer and his struggles to adjust his bloody prosthesis, and air raid sirens.

Their exchange takes the form of an intellectual sparring match between two smart and equally self-righteous men about the existence of God. They sprinkle their remarks with humor and powerful one-liners. Some favorites:

Lewis: Doctor, I’ll be the first to admit that the greatest problem

with Christianity are Christians. But you can’t reduce a faith

to an institution.

…

Freud: But Hitler learns from history. A warrior’s greatest

ally is always God.

…

Freud: His followers deified him. He performed magic trick

miracles. His strategy was a complete success.

Lewis: I wouldn’t call any strategy ending with crucifixion a

complete success.

…

At times it seemed as though the sharp-tongued Freud had the lead, what with the war raging outside and the one threatening his life from within. Having lost his 27-year-old daughter to the Spanish flu and his grandson to tuberculosis at five, Freud had ample reasons to question God’s beneficence.

Exalting the power and goodness of God, Lewis pins the blame for evil on man’s free choice. Freud’s angry rejoinder, “Is that your excuse for pain and suffering? Did I bring about my own cancer?”, garners an admission of ignorance from the now hesitant believer. Many a survivor of childhood abuse and neglect has similarly hurled accusations at the existence of any god let alone an all-powerful father figure running the show for the benefit of all.

Later in their conversation, after Freud has skewered Lewis with insinuations about his sexual behavior, the writer gets his turn, inquiring about the doctor’s overly close relationship with his daughter, Anna. Hearing that she had never married, remained devoted to her father, and wrote a paper on sadomasochistic fantasies based on her father’s psychoanalytic treatment of her, Lewis demurs from further questions and reminds Freud of the analyst’s earlier observation, “What people say is less important than what they cannot.”

By the end of the play, each has occupied the famous couch, both literally and figuratively. Out of the acrimony flying between them has sprouted spontaneous expressions of trust and concern, culminating in a rapprochement based on a shared joke and a mutual acceptance that faith by its very nature does not submit to proof.

Freud’s Last Session

Marjorie S. Deane Little Theater

West Side YMCA

10 West 64th Street

New York, NY 10023

(212)352-3101

Posted in Theater Reviews |

Print This Post Print This Post

January 30th, 2011

Addiction Blog

Interviews the Artist

- Toy Soldier (drawing).

After discovering the drawings of Toy Soldier and The Annunciation in the publication Addiction and Art, Lee Weber decided to interview this artist to gain some insight into “[h]ow addiction counselors use art to heal,” a topic of interest to readers of the Addiction Blog.

The thoughtful questions posed focused on this artist’s early experiences with creativity and ongoing involvement with art as a force for healing and enlightenment.

Access the interview at the Addiction Blog.

- The Annunciation (drawing).

Posted in Currently on View |

Print This Post Print This Post

January 23rd, 2011

Forever Young, Outsider Dalí

Danced with Old, Sparred with New

When photographer and friend Phillipe Halsman asked Salvador Dalí during a photo shoot, “Why do you wear a mustache?”, he received the response, “In order to pass unobserved.” When photographer and friend Phillipe Halsman asked Salvador Dalí during a photo shoot, “Why do you wear a mustache?”, he received the response, “In order to pass unobserved.”

Judging from the size of one of the massive crates required to ship his mural-sized paintings (revealed by an obliging museum guard in a behind-the-scenes peek) and the intense efforts Dalí expended to brand himself (long before anyone used that noun as a verb), he clearly intended that every endeavor generate attention, including the series of photographs that emerged from his work with Halsman.

Those Halsman-Dalí photos welcomed visitors to the High Museum of Art’s exhibit, Salvador Dalí: The Late Work. They combined portraits of Dalí with accompanying repartee. Following the question, “Why do you paint?”, and its answer, “Because I love art,” came an image of the artist with his mustache formed into an S turned into the American dollar sign with the addition of two paint brushes. Coins framed the face.

For only a time a Surrealist but forever associated with that movement, and famous for the melting clocks of The Persistence of Memory (1931), Dalí fell from grace early on because of his unapologetic commercialization of art. Assembled for the show at the High by guest curator Elliott H. King, a collection of Dalí’s late work aimed to situate this initiator of happenings and multimedia events, innovative sculptor, and expert draftsman and painter where he rightfully belongs: in the pantheon of great artists of the twentieth century.

In the first room of paintings, a vitrine contains Dalí’s copy of The Geometry of Art and Life by Matila Ghyka, opened to the page describing the Golden Section on which the book’s owner penciled notes that chronicled his efforts to understand it. In The Study for Leda Atomica (1947), Dalí inscribed a couple of phone handsets, a fully inked swan and Leda/Gala within an encircled pentagram, the construction lines for which intersect to divide into segments that relate to each other in accordance with the Golden Ratio.

Such geometric magic along with other scientific interests figured prominently in Dalí’s peculiar thought processes. The smashing of the atom, especially, captured his imagination and inspired depictions of disintegrating forms. Conceptualizing matter as reducible to an invisible state of energy suited Dalí’s philosophical and artistic wanderings in the insubstantial worlds of fantasy, dreams and the unconscious.

In addition to his prodigious visual output, Dalí wrote extensively on his favorite subject: himself. Among other topics, his musings expound upon his artistic choices, beginning with the paranoiac mechanism of his Surrealism days. Caught up in a multi-tracked train of thought, Dalí arrived at his Paranoiac-Critical mysticism, the underlying inspiration for much of the work in this exhibit.

Writing about his unique view of the world, Dalí aligned himself with paranoiacs who, he observed take “…advantage of associations and facts so refined as to escape normal people [to] reach conclusions that often cannot be contradicted or rejected and that in any case nearly always defy psychological analysis.”1 Indeed, this artist found relationships few others saw, morphing one object into another with his deft wielding of pen and brush.

Devoted to Dalí’s expeditions into the graphic arts, two rooms in the exhibit contained an array of styles and modalities that served as a good introduction to his extensive accomplishments in this arena. Unfortunately, late in his life he became fast and loose with his signature in a way that challenged future collectors and dealers in their attempts at authentication. On display, engravings from Ten Recipes for Immortality (1973) and colored lithographs from Don Quixote (1957) (both series inexplicably absent from the catalog) demonstrated Dalí’s expert draftsmanship. The High could do well to mount an exhibition devoted solely to this aspect of Dalí’s oeuvre.

Among the few early works included in the exhibit, Debris of an Automobile Giving Birth to a Blind Horse Biting a Telephone (1938) combined both Dalí’s paranoiac ability and his facility with both ends of a brush. On a dark ground, the artist scraped off paint to reveal form-defining lights and applied small dabs of color as highlights on the horse’s rump. With a radiator to its left, an automobile wheel in place of one of its forelegs and a fender over its other, this bio-mechanical animal bites down with a vengeance on a phone’s receiver, leaving the viewer to ponder what it might mean.

Dalí’s later works drew upon his fascination with quantum physics. In his Mystical Manifesto (1951), he unraveled the secrets of the Paranoiac-Critical approach and rallied aspiring artists to perfect their craft. When he wrote that the “mystical ecstasy is ‘super-cheerful,’ explosive, disintegrated, supersonic, undulatory and corpuscular, and ultra-gelatinous…,”2 Dalí included a reference to the quantum theory that energy exists in either wave (undulatory) or particle (corpuscular) form depending on the instrument used to observe it.

In an instructive example of his method, the Paranoic-Critical Study of Vermeer’s “Lacemaker” (1955), Dalí exploded his copy of the Dutch artist’s painting, at which he had spent an hour staring during a visit to the Louvre and then reproduced from memory (so the story goes). Insisting that he found four rhinoceros horns in Vermeer’s small image, Dalí included those in his updated version along with a recognizable face surrounded by strands and corpuscles of color and light.

The title of Saint Surrounded by Three Pi-Mesons (1956) directly references subatomic particles. Where others might see a person, Dalí utilized his paranoiac vision to reduce the holy figure to a mass of individual elements. This relatively small painting, housed in a protective glass-covered frame box, revealed a deftness of touch in the artist’s application of mostly grisaille daubs of paint interspersed with strokes of occasional blue in the face area and bronze on the hands. Golden tassels dangle at the bottom. An entire world exists in this assemblage of forms; reproductions barely hint at the effort required for its realization.

A devoted classicist, Dalí took issue with the art trends of his time. In a preparatory sketch for a page in his Fifty Secrets of Master Craftsmanship (ca.1948), displayed in the vitrine with the book on geometry, Dalí used parameters like “Grafmanschip, coleur, dessino” [all sic] to rate Mondrian, Picasso and himself alongside old masters such as Raphael, Leonardo and Velázquez. Picasso faired all right. Mondrian earned almost all zeroes, but so did Bouguereau.

Further expressing his negative feelings about nonobjective art, Dalí painted Fifty Abstract Paintings Which as Seen from Two Yards Change into Three Lenins Masquerading as Chinese and as Seen from Six Yards Appear as the Head of a Royal Bengal Tiger (1962), the name of which says it all. In the same room as that statement hung The Sistine Madonna (Quasi-grey picture which, closely seen, is an abstract one; seen from two meters is the Sistine Madonna of Raphael; and from fifteen meters is the ear of an angel measuring one meter and a half; which is painted with anti-matter; therefore with pure energy) (1958). A tromp l’oeil piece of paper and a cherry tied to the end of a string contrast in technique with the benday-dotted ear containing an image of a face.

Possibly one of Dalí’s most beautifully rendered paintings, The Madonna of Port Lligat (1950) showcases the wizardry with which this master could transform two-dimensional canvas into an imagined three-dimensional reality. With invisible brush strokes, Dalí lavished the same attention to detail on each object pictured. Brilliantly conceived, the Christ child that sits on the Madonna’s/Gala’s lap looks just like the neighbor’s kid, except for the end piece of a bread loaf that floats in the rectangular space carved into the youngster’s torso.

Two other floor-to-ceiling canvases deserve mention. In Christ of St. John of the Cross (1951), Dalí depicts the crucified figure from above, within an equilateral triangle, and suspends the cross high above a boat anchored in a large lake. Perhaps he intended the perspective to suggest God’s view of the event. Two other floor-to-ceiling canvases deserve mention. In Christ of St. John of the Cross (1951), Dalí depicts the crucified figure from above, within an equilateral triangle, and suspends the cross high above a boat anchored in a large lake. Perhaps he intended the perspective to suggest God’s view of the event.

Using a photograph of a horse’s head as reference, paranoiac Dalí noticed that the highlight on the creature’s neck resembled an angel. In Santiago El Grande (1957), the image reverberates throughout the huge painting. Over a blue latticework background, a rider mounted on a rearing stead hoists a golden cruciform figure. Fiery orange objects fly around in the uppermost lefthand corner. In the lower right, shrouded Gala peers out from behind her partly hidden face, confronting the onlooker with her one visible eye.

Not the last artwork displayed in the show but definitely a coda of sorts, The Truck (We’ll be arriving later, about 5 o’clock) (1983) captures the devastation Dalí suffered when his beloved wife and muse, Gala, died in 1982. Using a combination of oil paint and collage on canvas, this view from the inside of an opened-back truck alludes to “André Breton’s: ‘I demand that they take me to the cemetery in a removal van.’ The subtitle invokes Garcia Lorca’s ‘Lament for the Death of a Bullfighter’ (1935) refrain: ‘at five in the afternoon.’”3 Using a diluted brown and black wash, Dalí painted the interior with a seated figure silhouetted against a brightly lit exterior. A much darker mass close by looks like the painter at his easel, capturing the love of his life for eternity.

After Gala’s death, Dalí slipped away from life. His best work behind him, he spent the last years of his life an invalid. In 1989 when his heart gave out, the world lost a unique and gifted madman–and genius.

____________________________________________

1 “Selected Writings by Salvador Dalí,” Dalí, 2004, 550.

2 Ibid, 564.

3 Exhibit wall text.

Salvador Dalí: The Late Work

High Museum of Art

1280 Peachtree Street, NE

Atlanta, GA 30309

(404)733-4437

Catalog available.

Posted in Art Reviews |

|

Perhaps a detective in a previous life, Meryle Secrest can’t resist challenging a too-good-to-be-true story. Expanding on her work as a journalist, she relentlessly pursues facts behind myths surrounding larger-than-life artists and their supporters. Secrest’s efforts have thus far produced ten biographies, including psychologically insightful ones on Salvador Dalí and Romaine Brooks. As with her latest, Modigliani: A Life, she ferrets out family and childhood factors to illustrate their influence on the life and artistic development of her subjects.

Perhaps a detective in a previous life, Meryle Secrest can’t resist challenging a too-good-to-be-true story. Expanding on her work as a journalist, she relentlessly pursues facts behind myths surrounding larger-than-life artists and their supporters. Secrest’s efforts have thus far produced ten biographies, including psychologically insightful ones on Salvador Dalí and Romaine Brooks. As with her latest, Modigliani: A Life, she ferrets out family and childhood factors to illustrate their influence on the life and artistic development of her subjects.