News & Views

Print This Post Print This Post

November 14th, 2010

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt:

Sculptor of Pain

Many years ago in a mountain town in what is now Germany, a ten-year-old boy’s father dies and within months the child finds himself in an unfamiliar and urban environment after his mother moves the family to Munich to live with her brother. Soon after, the boy becomes an apprentice in his uncle’s sculpture studio. Years later as an accomplished portraitist, he produces over the course of 12 years a series of unusual heads that remain in his studio until after his premature death at age 47.

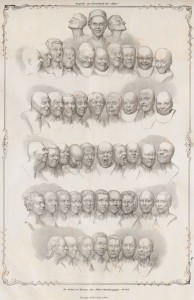

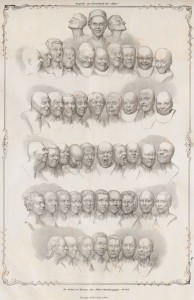

- Matthias Rudolph Toma (1792-1869), Messerschmidt’s “Character Heads” (1839, lithograph on paper), Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

Historical records provide little additional early biographical data on Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, the subject of that story and of an exhibit at the Neue Galerie, beyond those directly relevant to his artistic development. Born in 1736, by age 23 he had secured commissions from the royal family in Vienna, where he had moved six years before to study at the Academy of Fine Arts.

Hints of emotional instability surface by 1770, the year Messerschmidt’s financial success enables him to purchase a house in the suburbs. Coincidentally, that year also sees the death of his patron of 15 years, the artist Martin van Meytens (1695-1770). By 1771, at age 35, the sculptor’s life has unraveled.

Commissions have slowed to a trickle and the support he’s enjoyed as acting professor at the Academy evaporates. In 1774, when the Academy’s professor of sculpture dies, Messerschmidt–long considered his natural successor–finds advancement barred. The professors’ committee seizes this opportunity to free themselves of a man whose “…reason occasionally seemed subject to madness.”1 Further along the decision-making ladder, the State Chancellor reports that the artist is “not suitable for [the position]…because for the past three years he had demonstrated ‘some mental confusion’ and suffered occasionally from an ‘unhealthy imagination.’”2

During this period of time, in an attempt to prevail over his demons, Messerschmidt begins work on what will later be called–for lack of better understanding–“character heads,” sculptures depicting extreme facial expressions. His artistic talent and ability never desert him, as evident in the exquisite 1773-74? portrait of Prince Joseph Wezzel of Liechtenstein.

- Prince Josef Wenzel of Liechtenstein (1773-74?, tin cast), Sammlungen des Fürsten von und zu Liechtenstein, Vaduz-Vienna.

In 1775, Messerschmidt attempts to relocate. He fails to find room at his childhood home, tries Munich for several years, then in August 1777, finds a place to live and work in Bratislava (now part of Slovakia) with his younger brother, also a sculptor. Within three years he has purchased his own home outside the city, where a brief illness thought to be pneumonia, ends his life in 1783.

The Neue Galerie’s exhibition, Franz Xaver Messerschmidt 1736-1783: From Neoclassicism to Expressionism, showcases both the skill and eccentricity of this artist. Greeting the viewer at the entrance to the show, an oval screen mounted behind a drawn picture frame, part of an ornately decorated wall, runs a video showing the “character heads” morphing one into another, looking for all the world like the sculptor posing in front of his mirror.

The first gallery presents work from Messerschmidt’s Early Years in a spacious room with white walls covered with outlines of Baroque paneling and intricate scroll work. Occupying a vitrine in the center of the mostly empty space, six portrait heads dating from as early as 1769, but also as late as 1782, establish the skill with which the sculptor captured images in marble and metal, and perhaps also the soundness of his mind.

Standing on its own in a corner, the portrait of Prince Joseph Wezzel of Liechtenstein, like the uncaged sculptures in later rooms, draws immediate attention by the power of its achievement. Metal becomes flesh and hair, bringing to life one of Messerschmidt’s first patrons.

In the second gallery, the viewer meets the artist transformed. A chorus line of seven heads in a long vitrine kicks off the intriguing subject of Messerschmidt’s Character Heads, his motivation for creating them, and his mental state at the time.

The impossibility of knowing the exact etiology and nature of the sculptor’s breakdown has not deterred the propagation of hypotheses, beginning with Friedrich Nicolai’s account of his 1781 visit to the artist’s studio. In a skeptical and condescending tone, Nicolai made observations and shared what he managed to extract from the reticent Messerschmidt.

He learned that spirits “frightened and plagued [the sculptor] at night,” pursuing him despite his having “lived so chastely.”3 Following a convoluted line of reasoning that Nicola valiantly attempted to record and explain, Messerschmidt arrived at the belief that “the Spirit of Proportion was envious of him because he came so close to perfecting his knowledge of proportions and for this reason caused him those pains [in his belly and thighs].”4

Further, the artist imagined that “if he pinched himself in various parts of his body, especially on his right side amid the ribs, and linked this with a grimace on his face which would have the same Egyptian proportion required in each instance with the pinching of the rib flesh, the height of perfection would be attained” and therefore protect him from the spirits.5

Nicolai came to his own conclusions about what ailed Messerschmidt as did Ernst Kris centuries later in his 1932 book on the sculptor, elements of which appeared in the 1952 English translation of his Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art.6 Each naturally brought to the endeavor his own point of view, not unlike the blind men and the elephant. Nicolai embedded his assessment in the rational thinking of his Age of Enlightenment and Kris wrote in the psychosexual language of Freudian theory.

The “character heads”—the best place to start in any analysis of Messerschmidt—tell their own story, speaking volumes about him. Unfortunately, because no one has yet found a way to date them, they can’t be used to track the evolution of his condition. Nor has anyone had the courage to alter the misleading and sometimes comical names given them after Messerschmidt’s death.

As a group, the “character heads” suggest a person in great distress. Although Messerschmidt referenced his own mirror image, only some approach self portraiture, the rest depict types. Most of the sculptures have eyes shut so firmly that folds and wrinkles accrue around them. The ones with wide open eyes stare blankly at nothing in particular, an effect enhanced by the absence of pupils. A few open their mouths but the majority close them tightly, hiding their lips. By way of explanation, Messerschmidt pointed out to Nicolai that “men must simply pull in the red of the lips entirely because no animal shows it.”7

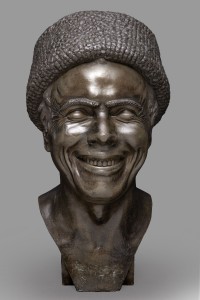

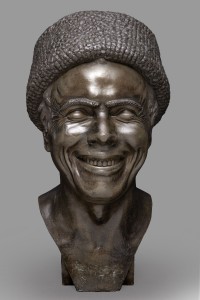

- The Artist as He Imagined Himself Laughing (1777–81, tin cast), private collection, Belgium

Messerschmidt’s suffering suffuses all his “character heads” including The Artist as He Imagined Himself Laughing. Closely resembling its creator, this sculpture presents a man in a lamb’s wool hat with a mouth open wide enough to show the top row of his teeth. As expected in any heartfelt grin, the action of the muscles that pull back the corners of the mouth push up the lower lids to cover the bottom of the eyes.8 That they come almost halfway up the eye belies the expression’s authenticity and provides evidence of the sculptor’s striking the pose for other than representational purposes, perhaps to openly challenge his demons.

![Plate 18, The Difficult Secret [Front] for site](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Plate-18-The-Difficult-Secret-Front-for-site-217x300.jpg) - The Difficult Secret (1771-83, tin cast), private collection, New York.

Anything but happy, The Difficult Secret expresses Messerschmidt’s pain in its eyes, where the action of the muscle raising the inner portion of the left brow pulls up the inner corner of the left upper lid.8 The downturned corners of the mouth, usually associated with disgust,9 coupled with the clenched lips, give the impression of grim determination. Each sculpture portrays Messerschmidt’s relentless battle to repel the evil spirits haunting him.

- A Hypocrite and Slanderer (1771-83, metal cast [lead-tin alloy?]), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Possessing one of the sillier names, A Hypocrite and Slanderer departs from the typical upright or slightly lifted head positions by tilting downward, requiring viewers to get on their knees for a complete view, raising the question of Messerschmidt’s own position while creating it. With the head retracting into the chest/body/self, this sculpture poignantly expresses the sculptor’s shame.

Messerschmidt could have unconsciously projected onto imagined evil spirits those impulses and emotions that his psyche found intolerable. Young children who lose a parent often blame themselves for the loss, remembering times when in a fit of frustration at a request denied, they wished their parents dead. For a child, the loss of a parent equates with abandonment and leads to diminished self-worth; after all, parents don’t leave good children. Without help, these children grow up harboring unanswered questions about early parental loss, and doubts about their own role in their parent’s death.

From age 19, Messerschmidt benefited from a relationship with the much older van Meytens, his early patron, perhaps more than just artistically and professionally. The 15-year bond with van Meytens provided an opportunity for the artist to receive care and attention from a father figure but might also have stirred up fears based on unconscious shame, guilt and rage from the long ago death of his father. In addition, the natural competition between student and teacher might have contributed to Messerschmidt’s projection of jealousy onto his demons following the man’s death, a manifestation of his guilt over seeking to best his mentor. Finally, consideration must be given to the possibility that the relationship with van Meytens had a sexual component, which would explain Messerschmidt’s lack of interest in women and his sexual conflicts.

When van Meytens died in 1770, Messerschmidt found himself awash in that little boy’s emotional turmoil. Adults who re-experience child feelings usually fear for their sanity because of the visceral and non-adult-like intensity of them. To preserve his ego, Messerschmidt regrouped by blaming his reactions on jealous demons who pursued him. Paranoid feelings can indicate projected guilt. When the paranoia overflowed into his work situation, the Academy had to get rid of him. Once again he found himself abandoned.

- Just Rescued from Drowning (1771-83, alabaster), private collection, Belgium.

- The Vexed Man (1771-83, alabaster), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

In two carved alabaster sculptures, Just Rescued from Drowning and The Vexed Man, Messerschmidt demonstrates his expert handling of the soft stone, incising impossible wrinkles to suggest aged skin and to emphasize the expression. With pursed lips, scrunched up noses, shut eyes and heads pitched forward, these old men anticipate imminent contact with something distinctly unpleasant. They brace for it and at the same time seem resigned to its inevitability.

- The Yawner (1771–81, tin cast), Szépművészeti Múzeum (Museum of Fine Arts), Budapest.

At first glance, The Yawner seems to be screaming, but a mouth that opens by lowering the chin into the chest impedes the flow of air in and out of the lungs, opposite of the maximum exhalation required for a scream. As for the work’s title, Darwin had this to say about yawning: “[It] commences with a deep inspiration, followed by a long and forcible expiration,”10 not possible under these circumstances. The vulnerability of the open mouth contrasts with the avoidance of the retracted tongue, squinting eyes, and nose wrinkled in disgust, indicating ambivalence–or more painfully, conflict–about the situation.

- Quiet Peaceful Sleep (1771-83, tin cast), Szépművészeti Múzeum (Museum of Fine Arts), Budapest.

The title bestowed by the anonymous author who originally named the “character heads” comes closest to accuracy in Quiet Peaceful Sleep. Here Messerschmidt has captured in a face devoid of the usual abundance of wrinkles an expression of peaceful resignation. Gently lowered upper lids close the eyes under a minimally knitted brow. The nose sits neutrally over a mouth that betrays some tension in its thinned upper lip, which rests on a full lower one. The expression brings to mind the state of the suicide shortly before an attempt, when despair has lifted enough to liberate energy for action; a calm descends on the victim who looks forward to final release/relief from pain.

For a full comprehension of Messerschmidt’s struggles, notice must be paid to the sculptures with bands across their mouths. If the tightly pressed and retracted lips in the rest of the heads fail to impress with their need to keep something in (or out), then slapping a strip across the mouth surely clarifies that intention.

Messerschmidt must have feared the power of his mouth to give voice to the taboo feelings he carried and perhaps also to divulge the true nature of his relationship with his early patron. Wrestling against that force, he left behind for posterity to ponder, beautifully crafted alabaster and metal portraits that continue to keep his secrets.

______________________________

1 Maria Pötzl-Malikova in Franz Xaver Messserschmidt 1736–1783, 21.

2 Ibid.

3 Frederich Nicolai, “Description of a Journey through Germany and Switzerland in the Year 1781, in Franz Xaver Messserschmidt 1736–1783, 208.

4 Ibid, 209.

5 Ibid.

6 Ernst Kris, Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art, 1971, 128.

7 Op cit.

8 Paul Ekman and Wallace V. Friesen, Unmasking the Face: A Guide to Recognizing Emotions from Facial Expressions, 1975, 104–5.

9 Ibid, 117–119.

10 Charles Darwin, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, [1872], 1989. 165.

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt 1736-1783:

from Neoclassicism to Expressionism

Neue Galerie

1048 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10028

(212)628-6200

Catalog available.

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post Print This Post

November 5th, 2010

Economic Bubbles

& the Brain

Like many people, Read Montague wondered about the inevitable cycles of boom and bust that plague economies. Being a neuroscientist, he devised an experiment to find out what happens in the brain when investors continue to pour money into businesses, real estate, stocks, and gold, despite the inevitable tumble destined to follow when values rise beyond reason during times of irrational exuberance.

An article in the New York Times Magazine described how Montague gave subjects $100 each to play a game where they invested in various market situations that unbeknown to them mimicked historical rises before crashes. During the game, Montague monitored their brain activity.

At the beginning, on the economic upswing as the players amassed profits, their brain activity showed nothing unusual. In keeping with the good feeling that accompanies gratifying experiences, neurons pumped out dopamine, the reward neurotransmitter. As subjects continued to benefit from the rising market, the dopamine increased their excitement and spurred on more investing as they scrambled for money.

After a while, something strange happened. Nearing the time the bubble would burst, the neurons slowed production of dopamine, as if to say, “Whoa, there!” Then just before the run ended, the dopamine neurons stopped firing completely. Rather than heed the cautionary feeling of that change in mood, investors continued putting money into the market, rationalizing the risks by reasoning their good fortune would go on forever. The prefrontal cortex, center of higher brain functions like cognition and self reflection, overrode the intuitive feeling in the rest of the brain.

Ordinarily, engaging cognition to manage emotional responses works out well. Apparently, there are times when thinking processes only serve to justify and defend behaviors that when considered from a different perspective, wouldn’t really make sense. The prefrontal cortex possesses enormous powers of self deception that can be tempered by paying attention to feelings, a valuable source of additional information.

Posted in Therapist Musings |

Print This Post Print This Post

November 3rd, 2010

Psychiatry Treats Symptoms

Not Patients

Half of the adolescents treated for depression in a recent study suffered a recurrence of symptoms within five years. The study, reported in the New York Times, also found that girls were more likely to relapse than boys. The research protocol consisted of three options: an antidepressant, cognitive behavioral therapy, or a placebo pill.

About the results, the study’s lead author concluded, “It looks like we don’t have a treatment yet that really prevents recurrence.” In searching to explain the increased vulnerability of girls to relapse, he offered, “Maybe it has to do with something in girls…stressful life events or the way people cope with stress.” A doctor who was not part of the study suggested it might be linked to hormonal changes or that “women tend to brood more, so the slightest stress is multiplied many times.”

Doctors so caught up in the biological aspects of depression stray from the reality of life for teenagers in general, and the particular challenges faced by so many adolescents who have suffered various kinds of trauma: from childhood sexual abuse to living in violent neighborhoods, from loss of a family member to having serious medical problems. The list is, unfortunately, endless.

In choosing possible protocols, the researchers left out psychotherapy, that practice of engaging in conversation with the person who suffers. Instead, treatments were selected based on their uniformity of practice and hence replicability by others; psychotherapy does not lend itself to standardization because of its focus on relationship.

Meanwhile, the adolescents get lost in the process. The girls, more likely to have experienced sexual abuse than boys, get blamed for not being able to handle the stress in their lives. They “brood.” Perhaps the problem lies not with the teenagers but with adults unable to handle finding out what truly ails these young people.

Posted in Therapist Musings |

Print This Post Print This Post

October 24th, 2010

Toy Soldier Drawing

To Appear at CSAT

Funding Meeting

In her continuing efforts to tap into the power of art, Patricia Santora, PhD, Public Health Advisor at SAMHSA, plans to display six of the works from Addiction and Art at the annual meeting of the grant division of CSAT in Arlington, Virginia, from November 15-17, 2010. At the request of the project officers, the Toy Soldier drawing will be represented by a full-scale reproduction. In her continuing efforts to tap into the power of art, Patricia Santora, PhD, Public Health Advisor at SAMHSA, plans to display six of the works from Addiction and Art at the annual meeting of the grant division of CSAT in Arlington, Virginia, from November 15-17, 2010. At the request of the project officers, the Toy Soldier drawing will be represented by a full-scale reproduction.

In an email communication with the artist, Dr. Santora explained, “Numerous topics on substance abuse treatment will be discussed during this 3-day meeting that will draw about 500 participants. As you know, a typical scientific poster display highlights innovative prevention and treatment initiatives, and the meeting will feature scientific posters from the 140 federal grants that were awarded on this topic. Our plan is to create a small addiction art gallery that includes…art as part of this scientific session–addiction art integrated with addiction science.”

Dr. Santora looks forward to upcoming opportunities for sharing the Toy Soldier drawing and other Addiction and Art images at meetings of substance abuse professionals.

Posted in Currently on View |

Print This Post Print This Post

October 22nd, 2010

All are invited to a studio sale on

Saturday, November 20, 2010, 1-6pm and

Sunday, November 21, 2010, 2-5pm

Take advantage of this opportunity to purchase affordable artwork for yourself and as gifts for the upcoming holidays. Stop by to chat with the artist about her work. Take advantage of this opportunity to purchase affordable artwork for yourself and as gifts for the upcoming holidays. Stop by to chat with the artist about her work.

Paintings and drawings will be available for less than $100, and sketches starting as low as $5. Recent work will also be on display.

Call (212)673-7909 for address and directions.

Posted in Currently on View |

Print This Post Print This Post

October 7th, 2010

The Lethality of the Ordinary

Upon entering the theater, audience members received a program with an insert containing a brief description of the story about to unfold. On the reverse, a facsimile of a handwritten letter explained how Casey, the victim, acquired marks on her stomach that read, “I am a prostitute and proud of it.”

Providing the plot outline before the lights go out removes a major source of dramatic tension and situates the focus on character development and relationship exposition. Based on a crime committed in 1965, Down There (at the Axis Theater Company), imagines answers to questions posed by the murder of teenager Sylvia Marie Likens: “How could a diverse group of people of various ages who went to school, interacted with others, had their own families, ate snacks and played return daily to a basement and torture a girl to death? And: Why didn’t Sylvia run away? What was in her personal condition that allowed her to understand her abuse as something normal?” (From the press release.) Providing the plot outline before the lights go out removes a major source of dramatic tension and situates the focus on character development and relationship exposition. Based on a crime committed in 1965, Down There (at the Axis Theater Company), imagines answers to questions posed by the murder of teenager Sylvia Marie Likens: “How could a diverse group of people of various ages who went to school, interacted with others, had their own families, ate snacks and played return daily to a basement and torture a girl to death? And: Why didn’t Sylvia run away? What was in her personal condition that allowed her to understand her abuse as something normal?” (From the press release.)

To solve that mystery, writers Randy Sharp and Michael Gump conjured up the Menckl family, whose pathological dynamics make it well qualified to kill. One formed by accretion rather than procreation, it consists of Pat, the long-suffering mother; Frank, the disabled, unemployed, alcoholic father; and Jim, the developmentally disabled son with psychiatric problems. Acquired members include John, Rickie and Paula, older teenagers, soon joined by polio-stricken Joyce and her protective 16-year-old sister Casey. These relationships coalesce slowly, leaving viewers in an unsettled state not unlike that of those on stage.

The action reveals how one person’s rage has the power to infect others. Pat projects her own misery onto those around her and enlists her charges to assist her in scapegoating and eventually killing a child she agreed to foster. She viciously berates Paula for eating candy, calling her a fat girl who nobody will want. Endlessly complaining about her various ailments, she takes pain pills to cope with a bad back and Jim’s pills for her nerves. Attracting stray children for the money their care brings, she seethes with resentment over the insufficiency of the remuneration and directs her anger at the kids and Frank.

When Casey arrives, she brings with her a certain vibrancy and sense of entitlement that immediately irritates Pat, who accuses her of coming on to the boys in the house. Meanwhile, Pat embraces Jim more like a lover than a son. As time goes on, Pat observes that Frank’s drinking picked up after Casey’s arrival and blames the child for that, too.

None of it makes any sense and yet the chaos enacted leads inexorably toward the imprisonment of Casey in the basement and the deprivation and abuse that result in her slow and painful death. The audience finds itself caught up in the vortex of fast-paced, disjointed action, drawn into the role of helpless bystander. After the play ended, many remained fixed in their seats, too stunned to move. None of it makes any sense and yet the chaos enacted leads inexorably toward the imprisonment of Casey in the basement and the deprivation and abuse that result in her slow and painful death. The audience finds itself caught up in the vortex of fast-paced, disjointed action, drawn into the role of helpless bystander. After the play ended, many remained fixed in their seats, too stunned to move.

How closely do these fictional characters resemble the actual participants in the 1965 crime? If not taken from life, how ever were they dreamed up?

In an interview, writer and director Sharp explained her need to figure out how terrible things occurred. “They’re more frightening if they’re inexplicable, less scary if you can figure out why things happened.” Back in the ’60s when she first learned about the murder of Sylvia Likens, it blew her mind that it had taken three months for the victim to succumb and that during that time, nobody noticed.

She imagined the dialog and, using the information available about Gertrude Baniszewski, the real mother, she created a character that retained some of her personality, including the pill popping and eating disorder (anorexia). Gertrude didn’t have a developmentally disabled son and the neighborhood children who participated were many and as young as 11.

Running an online search on Sylvia reveals memorial websites, some with detailed information about the fate of the murderers. Apparently Sharp wasn’t the only one appalled and perplexed by the ability of one woman to mastermind the death of a teenager in this way.

In her drive to understand the minds of these perpetrators, Sharp successfully deployed a cast of characters with the right mix of ordinariness and strangeness to account for the invisibility and lethality that enabled them to torture and murder in plain sight.

Down There

Axis Theater

1 Sheridan Square

New York, NY 10014

(212)887-9300

Posted in Theater Reviews |

Print This Post Print This Post

October 5th, 2010

Gottfried Helnwein:

“I Was a Child”

Wandering through the Friedman Benda gallery in Chelsea, the viewer encounters large format, hyper-realistic paintings of children with expressions ranging from inquisitive to apprehensive and sad. Not unknown in the United States, the creator of these works, Austrian expatriate Gottfried Helnwein, currently enjoys an opportunity to introduce his subjects to a broader audience with his first full-scale exhibition in New York.

- The Murmur of the Innocents 3 (2009, oil and acrylic, 87″ x 130″)

The painting that greets visitors, The Murmur of the Innocents 3 (2009, oil and acrylic, 87″ x 130″), in its relative innocent portrayal of a young blond girl in a camisole, barely hints at the distressing depictions that follow.

- The Murmur of the Innocents 16 (2010, oil and acrylic, 86″ x 130″)

Several of the other works in The Murmur of the Innocents series contain images of a girl in a military-like, navy blue jacket with epaulets and gold braiding on the cuffs, (numbers 16, 17, 18, 19 and 20). Three of these are closeups of the girl’s face, one has her left hand covering half her face, perhaps wiping a tear from her eye, and the first shows her from the shoulders up, lying near a pool of red with bloody nose and blood-soaked hair.

- The Murmur of the Innocents 20 (2010, oil and acrylic, 71″ x 47″)

Lest there be any doubt that these images speak about the impact of violence on children, in number 5, the young blond girl from the first painting, now dressed in a long white undershirt, holds a machine gun pointing to the right of the viewer and looks sideways at a cool green, toy manifestation of a cartoon character, reminiscent of Roo from Winnie the Pooh, who stands with hands on hips and stares back.

- Untitled (Disasters of War 24) (2010, oil and acrylic, 195″ x 243″)

In another piece, Untitled (Disasters of War 24) (2010, oil and acrylic, 195″ x 243″), a child with a gauze bandage wrapped around forehead and eyes, wears a white lab coat with epaulets and decorative cuffs, and points a large pistol at an icy blue girl doll, passing along the legacy of violence.

How does an artist come to such subject matter? Helnwein, born in 1948 in Austria amid the devastation that was Vienna at the time, grew up in a world that offered abundant evidence of humans’ capacity for cruelty. In an interview with Peter Frank, posted on the gallery’s website, he had this to say:

Maybe it’s a defect, yet ever since my earliest childhood I have seen violence all around me, as well as the effect of violence: fear. I absorbed any piece of information I could get hold of on persecution and torture like the Holocaust, the Vietnam War, tyrannical regimes such as that of Pinochet’s Chile, the Inquisition…and finally, the general mistreatment of children.

The obsession with inflicting maximum pain on others, in particular on the defenseless, that runs throughout human history has always been a mystery to me. The creativity that people develop in committing such atrocities is startling.

How can someone show anything but love and admiration to children? I have seen pictures taken by forensic doctors of children who had been tortured to death, often by their own parents, images that will not let you sleep well for awhile.

That was the reason I began to paint: aesthetics were not my primary motivation.

By the age of 18 I finally realized that art was probably the only possible way of defending myself against the impertinences of society. For me art was a weapon with which I could finally strike back.

Less a defect than a search for meaning, Helnwein’s acute awareness of ambient violence stems from his own childhood immersion in the visual evidence of its ubiquitous nature. His artwork forces viewers to confront the same mysteries of human nature’s dark side that have long troubled him.

“I Was a Child”

Gottfried Helnwein

Friedman Benda

515 West 26th Street

New York, NY 10001

(212)239-8700

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post Print This Post

September 26th, 2010

Drawing Against the Grain:

Gerhard Richter on Paper

“I could do that,” a girl of about 11 declared to her father as she glanced at Drawing III, one of four large-format drawings that covered the far wall during the exhibit, Gerhard Richter “Lines which [sic] do not exist” at The Drawing Center. “That’s where you’re wrong,” he countered, though never explaining how a collection of graphite lines, smudges, shadings and erasures, representing nothing recognizable, qualified as accomplished art.

Of this group (all 2005, graphite on paper, 59½” x 40⅜”), Drawing II garnered more interest from some viewers, one of whom when asked expressed appreciation for the variety of lines, contrast and use of erasures. The best of the four, the drawing achieved, in two central areas of smudging and erasure, effects similar to those found in many of the artist’s abstract paintings from 2000.

Arranged on the walls around the rest of this nonprofit exhibition space, smaller drawings and occasional watercolors rested on individually constructed, lipped, wooden shelves painted white. In an arrangement governed by no particular ideology, the display reflected the artist’s well-known approach to art making. Never one to run with the crowd, Gerhard Richter has always found his own way in his explorations of the infinite possibilities of paint and other media. The idea for the physical presentation and absence of order, according to Brett Littman (The Drawing Center director), belongs to the current venue; though Richter approved the show, he did not hang it like he has done elsewhere.¹

- Gebirge/Mountains (1968, graphite on paper, 19¼” x 21½”), permanent loan from a German private collection, courtesy Kunsthalle Emden.

This show, featuring less well-known aspects of Richter’s practice, displayed over 50 mostly small format works on paper that included wanderings with graphite pencils, sticks and perhaps powder–with minor assistance from an electric drill–and a few ink and watercolor pieces.

The title refers to a statement by the artist on the difference between his paintings and drawings in their closeness to representation. Because of the use of color in his paintings, even abstract ones, they come closer to reality, he believes, in a way that his drawings don’t.² Richter uses the traditionally held belief that lines don’t exist in nature to position his drawings further from the real world than his paintings.

Because Richter was born in Germany in 1932, his personal history coincides with that country’s descent into the darkness of first the Nazi era and World War II, then the partitioning of Germany and Berlin into the Communist east and capitalist west. Raised by a mother who spoke contemptuously to her son of her absent husband–drafted, then captured during the war–Richter confirmed not so long ago what his mother had always intimated, that the man who raised him was not his birth father.³

Not surprisingly, Richter developed a deep and abiding suspicion of any ideology– political, intellectual or artistic, and an allegiance to none. In striving in all his endeavors to steer clear of any identifiable attachments, he has created a unique and varied body of work.

Explored in the thoughtful catalog written by the curator, Gavin Delahunty, Richter’s relationship to drawing begins with a certain skepticism about its potential for flaunting virtuosity and his lack of faith in his own facility for it.4 A review of the exhibit’s offerings belies that self assessment and lends credence to Littman’s suggestion that the artist is “self negating.”5 Here Richter has plenty of company; artists criticize their work far more harshly than others.

Far from reflecting lack of skill, Richter’s works on paper suggest a child playing with new toys, though for this artist the novelty never seems to wear off. From the first to the last, each piece illustrates an experiment in the application of graphite (and sometimes watercolor and ink) in Richter’s determined search for the beautiful image.

- 22.4.1990 (1990, graphite on paper, 8¼” x 11-11/16″), courtesy Kunsthalle Emden.

The first hint of that exploration appears in a drawing at the very beginning of the exhibit. In 22.4.1990 (8¼” x 11-11/16″), the viewer encounters delicately applied dabs of graphite of differing weights progressing from darker to lighter as they march across the page from left to right, interrupted along the way by randomly spaced vertical erasures that lend the image depth.

Taking that inquiry further, in 1.6.1999 (8¼” x 11-11/16″) Richter adds scribbled graphite lines of assorted weights over a lightly shaded horizontal swatch covering a bit more than half of the drawing’s lower portion and the considerably darker one above it. Using an eraser, he creates two shining orbs in the dark, two smaller ones in the light, and horizontal and vertical lines–the sum total of which suggests a landscape on another world.

- 27.4.1999 (5) (1999, graphite on paper, 8¼” x 11-7/8″), private collection.

In discussing abstract art, Richter has described it as “narratives of nothingness” that prompt viewers to search for recognizable patterns.6 But he has also acknowledged the importance of landscape throughout his ouevre7, which invites the question: How many of these drawings hide attempts to capture the essence of reality beneath abstract imagery?

- 20.9.1985 (1985, graphite on paper, 8¼ x 11-11/16″), courtesy Kunsthalle Emden.

The only clearly representational image in the show, 20.9.1985 (8¼” x 11-11/16″, graphite on paper) highlights Richter’s exquisitely sensitive line. In it, a bare-breasted woman reclines on her back with her left arm extended toward the edge of the picture plane, bending at the elbow to run parallel to it and ending with the hand holding open a book. Varying line weights and delicate hatch marks combine to form a landscape that ends with several horizontal lines above the woman’s contour. Cutting off the head with the left edge of the paper enhances the perception that the image represents more than a woman lying on the beach. It hints at the inherently abstract nature of reality.

The delicacy of Richter’s application of graphite on smooth and toothed paper, coupled with the experimental nature of his mark making, lends his drawings lightness of being. While some fall short, many come close to that beautiful abstract reality Richter courageously pursues.

¹ Brief interview with Brett Littman, September 11, 2010.

² Gavin Delahunty, Gerhard Richter “Lines which do not exist,” 2010, 20.

³ Michael Kimmelman, “An Artist Beyond Isms,” The New York Times Magazine, January 27, 2002, 21.

4 Interview by Robert Storr in “Gerhard Richter: The Day is Long,” Art in America, January 2002, 72.

5 Littman, 2010.

6 Kimmelman, 24.

7 Dietmar Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, 2009, 269-277.

__________________________________

Gerhard Richter “Lines which do not exist”

The Drawing Center

35 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10013

(212)966-2976

Catalog available.

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post Print This Post

September 24th, 2010

Mirror, Mirror…

Who Am I?

A mother looks at her grown son and fails to recognize him. A brother looks at his identical twin and denies his existence. An identical twin looks in the mirror and finds his true brother. Actors acknowledge the audience that watches them. In his latest creation, Me, Myself and I, Edward Albee finds a way to amuse and entertain while at the same time confronting deep psychological issues of identity formation. A mother looks at her grown son and fails to recognize him. A brother looks at his identical twin and denies his existence. An identical twin looks in the mirror and finds his true brother. Actors acknowledge the audience that watches them. In his latest creation, Me, Myself and I, Edward Albee finds a way to amuse and entertain while at the same time confronting deep psychological issues of identity formation.

Before the red curtain rises, a young man dressed in black pants and grey shirt comes on stage to set up the action, revealing directly to the audience his intention to stir up family matters so he can extricate himself from them. Identifying himself as OTTO, he pins his hopes on getting rid of his identical twin, who soon joins him on stage in clothing reflecting his own, but fails to get OTTO to acknowledge him.

The curtain goes up to reveal a woman (Mother) in a nightdress, sitting up in bed painting her toe nails. Another person remains hidden under the cover but a bowler hat on the headboard suggests the presence of a man. Soon enough, the man–Mother’s doctor (Dr)–emerges, fully dressed in business attire.

When OTTO joins them, Mother greets him with, “Who are you? Which one are you?” She can only identify his brother because he’s the one who loves her. Dr has no trouble telling the twins apart because, he explains, neither of them love him. In fact, both twins resent him for taking their father’s place soon after he disappeared. When OTTO complains, ‘You never tell me who I am,” Mother continues to insist, “I don’t know who you are.”

OTTO possesses no small amount of rage toward his mother and the interloper Dr, though camouflaged by his remarkably subdued tone, and entertains the fantasy that his father will come back some day “if only to apologize for sticking me with you.”

Eventually OTTO announces that he has decided to become Chinese. He’s tired of being occidental and anyway the future lies in the East. When Mother asks whether his brother is going with him, OTTO says yes, but clarifies it’s a new brother–the old one no longer exists–and exits, leaving Mother and Dr to digest what just happened.

Mother reminisces about the time 28 years before when she learned she would be having identical twins and how her husband abandoned her following his visit to the delivery room. The first time she held the newborn boys, for that single moment she recognized them. In this disjointed conversation with Dr, Mother defends how she named one OTTO (loud) and the other otto (soft). Dr, always frustrated with Mother’s absurdities, admonishes her for sowing similar chaos from the stage: “…you’re confusing them, and a confused audience is not an attentive one, I read somewhere.”

The profound impact on OTTO of being raised by a narcissistic mother who refuses to see him because he won’t lavish her with adoration becomes poignantly apparent later in the play when he explains his new twin. Always before when he had looked in the mirror he had been afraid to touch himself, fearing he didn’t exist and neither did the image reflected back to him. His resolution of that unbearable state creates a split between himself and what he sees when he decides that even though it looks exactly like him, it’s actually his twin.

The question of identity must resonate with this playwright. Albee was born in 1928 and, as an infant, was adopted by a wealthy couple who “didn’t like children.” He admitted in a recent Playbill interview, that he “didn’t get along very well with [them].” Though his adopted parents provided him with a top-notch education and other physical comforts, “they were bigots” and at 18, Albee left because they disapproved of his homosexuality. He has never sought out his birth parents–back then no one could get access to adoption records–and now claims it “troubled [him] only for health reasons.”

The play resonates with elements of Albee’s own experience of knowing nothing about his origins and having adopted parents ill equipped to provide the nurturing he needed to begin to fill that void. Because he differed so markedly from them, they also failed as models, leaving Albee to invent himself. As for twins, he had this to say about them in the Playbill interview: “I think I decided I was probably an identical twin myself. Being an orphan, you need all the identity you can get. I never knew whether I had any brothers or sisters so I invent them in my plays.”

The parents he invents suggest comparison with his history as well. In Me, Myself and I, OTTO’s mother refuses to acknowledge her son’s unique identity, and his father, who abandons him, gets replaced by an imposter. Children born with temperaments radically different from their parents’ often believe they must have been adopted and fantasize about their real parents showing up to retrieve them. Albee stages just such a fantasy late in the play, though in the end it fails to achieve the hoped for happy ending.

The brilliance of this play lies in its sly use of language to disguise the pain OTTO must feel. Through exaggerated characters, humorous exchanges and bizarre situations, Albee leaves the audience mildly dazed. Perhaps the method in the madness that sows confusion creates just enough distance from the reality of the content to maintain the audience’s attention. When the fog lifts, more will be revealed.

Me, Myself and I

Playwrights Horizons

Mainstage Theater

416 West 42nd Street

New York, NY10036

(212) 564-1235

Posted in Theater Reviews |

Print This Post Print This Post

September 13th, 2010

Collaboration or Imposition:

Can Directing Rewrite a Script?

On a stage floor and backdrop of unfinished plywood populated by a woman, a man, two chairs, a pen light, an eye patch, a cymbal and furniture leg, and a baby grand piano, Vision Disturbance tells the story of an unlikely relationship between an ophthalmologist and his patient.

In her newest play, Christina Masciotti mines her own childhood experiences to create two characters from disparate worlds who share a knack for bending language to better suit their needs. The patient, Mondo (short for Diamondo), brings her world into the examining room where she presses Dr. Hull for a quick cure for her malady, diagnosed by him as Idiopathic (cause unknown) Central Serous Chorioretinopathy, a blurring of vision in one eye that he attributes to stress. While he prescribes and treats her with music to help her relax, she shares with him and the audience the ongoing drama of divorce proceedings she recently initiated against her philandering husband.

Directed by Richard Maxwell and produced by the New York City Players, Vision Disturbance relies heavily on dialogue between the two characters and monologues directed at the audience. Mondo, an emigre from Greece, effectively fractures English idioms to enhance their communicative power. Dr. Hull’s utterances, mostly devoid of emotion except when punctuated by chilling expressions of rage, say more than he can imagine.

- Dr. Hull (Jay Smith) eyes Mondo (Linda Mancini). Photo courtesy New York City Players.

Describing her situation, Mondo explains that she’s “between a rock and hell.” About her husband of 13 years, she says he’s “the scum of the dirt.” Dr. Hull, living upstairs from his mother, tells Mondo about his old cat, Socks, who enjoys being pulled up by his tail as he clutches the carpet with his claws. The doctor, yet to master the intricacies of his smart phone, promises Mondo he’ll call a lawyer friend for her “if I can work this; I keep taking pictures of my ear.” He deals with the lawyer’s refusal by cursing at him and later, when the phone rings, hurls it across the stage, explaining that he still hasn’t figured out how to turn it off.

When Dr. Hull prescribes music as a de-stressor for his patient, initially he has in mind its soothing power. But for Mondo, it’s most effective as an outlet for her anger not just at her husband’s betrayal, but also at the traditional Greek culture that provides men with that kind of freedom while constraining women to serve them. In one of their sessions, when her doctor gives her the furniture leg to use on the cymbal, she goes at it with verve, filling the theater with loud, unnerving reverberations. Later she’ll find great relief in the percussive power of the piano, which will fall apart under her pounding.

As more comes to light about Dr. Hull’s own affliction–back pain diagnosed as arthritis for which he takes lots of pain pills–and the narrowness of his life, one wonders whether he wouldn’t benefit from some of his own music therapy. The patient with visual problems displays the clarity that the doctor lacks. The wounded woman finds her way at the same time the man in authority loses his.

Masciotti’s script provides the perfect vehicle for Maxwell’s direction, known for its reductionism. Stripping it bare of stage directions that include a doctor’s office, a front door that Mondo opens to find a box with the eye patch she ordered (in the production, she retrieves the box from the top of the piano) and head gear for a special eye examination, Maxwell substantially changes the visual aspects of the play. The character of the actors’ speech probably owes more to Maxwell’s inclination to drain tone from speech and focus attention on content than to Masciotti’s original vision for the play.

Maxwell’s directing style works well here; his simplifications spotlight Masciotti’s skillful dialogue and take advantage of her indifference to stage directing. But when a seasoned playwright and director like Maxwell picks up a script of a writer whose day job is teaching college math, the situation has the potential to devolve into the same power struggle between the sexes portrayed in Mondo’s narration about her marriage and subsequent divorce proceedings.

Vision Disturbance demonstrates in its content as well as its style the transformative power of relationships. The play’s coda, anchored in Masciotti’s original ideas for the staging, will surprise and delight the audience, revealing a musical setting that supports the characters as they grapple with the uncertainty of newly altered roles.

Vision Disturbance

Abrons Arts Center

Henry Street Settlement

466 Grand Street

New York, NY 10002

(212)598-8329

Posted in Theater Reviews |

|

![Plate 18, The Difficult Secret [Front] for site](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Plate-18-The-Difficult-Secret-Front-for-site-217x300.jpg)